An Odyssey for Children (and Other People)

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. This week marks the launch of a new format where several regular columns run alongside one another. Feel free to write in to share your thoughts on the content or format, and please subscribe and share with friends.

Editor’s Note: Turn that Simile Upside Down

Editor’s Note is a regular column introducing issues, themes, and frameworks from a personal perspective.

My main reading project for June was Daniel Mendelsohn’s new translation of The Odyssey. It was a fruitful project working through dense verse, as this translation is notable for maintaining not only the poetic register but also the archaic tone and repetition of the original. Since Nostos shares a namesake with the Homeric epic traditions, referring to the Nostoi or the lost third of the trilogy relating the homecomings of the Greek heroes of the Trojan War, I thought I’d share a couple of my favorite moments from everything I’ve learned. I am not a specialist here, or even particularly well-read in any of this, so let me lead with amateurish passion.

The first thing, and what we have to start with, is that the structure of The Odyssey is nothing like the cinematic retellings and abridged translations that we are used to. Only four of its twenty four books really tell the story of Odysseus’s journey home, and even then they are told over a series of meals in retrospect, told as much to impress a host and push the trip forward as anything else. Almost all of the action and most of allusions to mythology comes in asides in which Odysseus or a bard or a marginal character relates past action. There is not a lot of Odyssey in The Odyssey! It is much more concerned with homecoming than it is with the journey. And indeed, the concept of heroism that we relate to The Odyssey—the hero’s journey—is very nearly disavowed. When Odysseus meets Achilles in the underworld, Achilles expresses something like regret for his choice to die with valor and be remembered by all men. Better to get yourself home. To quote Juergen Teller: better to live.

The second thing relates to the culture of xenia, or the etiquette of hosting. In the era of the narrative it is expected that an honest traveler be met with not only the basic hospitality of a meal and a place to stay but also, if his status registers, treasured gifts from the household. If there is some connection between them, they become “guest-friends,” linked out of courtesy going forward. Much of the bad luck and divine retribution meted out over the course of the journey is related to the righteous appeal to or wrongful abuse of xenia networks, seen clearly not only in the massacre of the suitors on Ithaka but also in the murder of Agamemnon upon his return from Troy.

Third and finally, there is this fantastic literary device deployed a number of times throughout the text called the reverse simile, which I wouldn’t have paid attention to at all without Mendelsohn’s helpful footnotes. Essentially, Homer describes a character in a way that inverts his/her gender, social status, or role in the situation. In its first appearance, Odysseus is alone at sea, buffeted by a storm, and catches sight of land. Oddly, his state of mind is described “Just as a father’s children would welcome some sign of life.” He is, of course, the father whose children would welcome some sign of life, and yet the psychology of his distant son is transposed onto his person—the man is the shore, the man is the child. In another scene, Odysseus begins to weep hearing a bard recount the adventures of the Trojan War. He is described weeping “Just as a woman would weep while embracing a beloved husband who … has fallen defending his town and his children.”

In my favorite example, he considers murdering the slave girls sleeping with the suitors, “Snarling just as a bitch, circling around her tender newborn pups when she’s faced with some unknown man, will snarl.” In the last instance, he weeps as he embraces Penelope, “Just as the sight of land is welcome to swimmers at sea.” This final appearance, I venture, is hardly as much of a reversal as the other half dozen appearances, but it shares with all of them a radical empathy that I find beautiful. This reversal of male and female, friend and foe, accomplishes two things: it upholds the virtuous cycles of the xenia system of host and guest, and it sanctifies the loyal union of marriage that makes for the foundation of the yearning for home that underlies the whole story.

Icon: Meret Oppenheim

Icon is a new regular column pairing canonical works of art and quotations from pioneering figures in the history of art and life.

“You can be a perfect and total and complete woman without kids.”

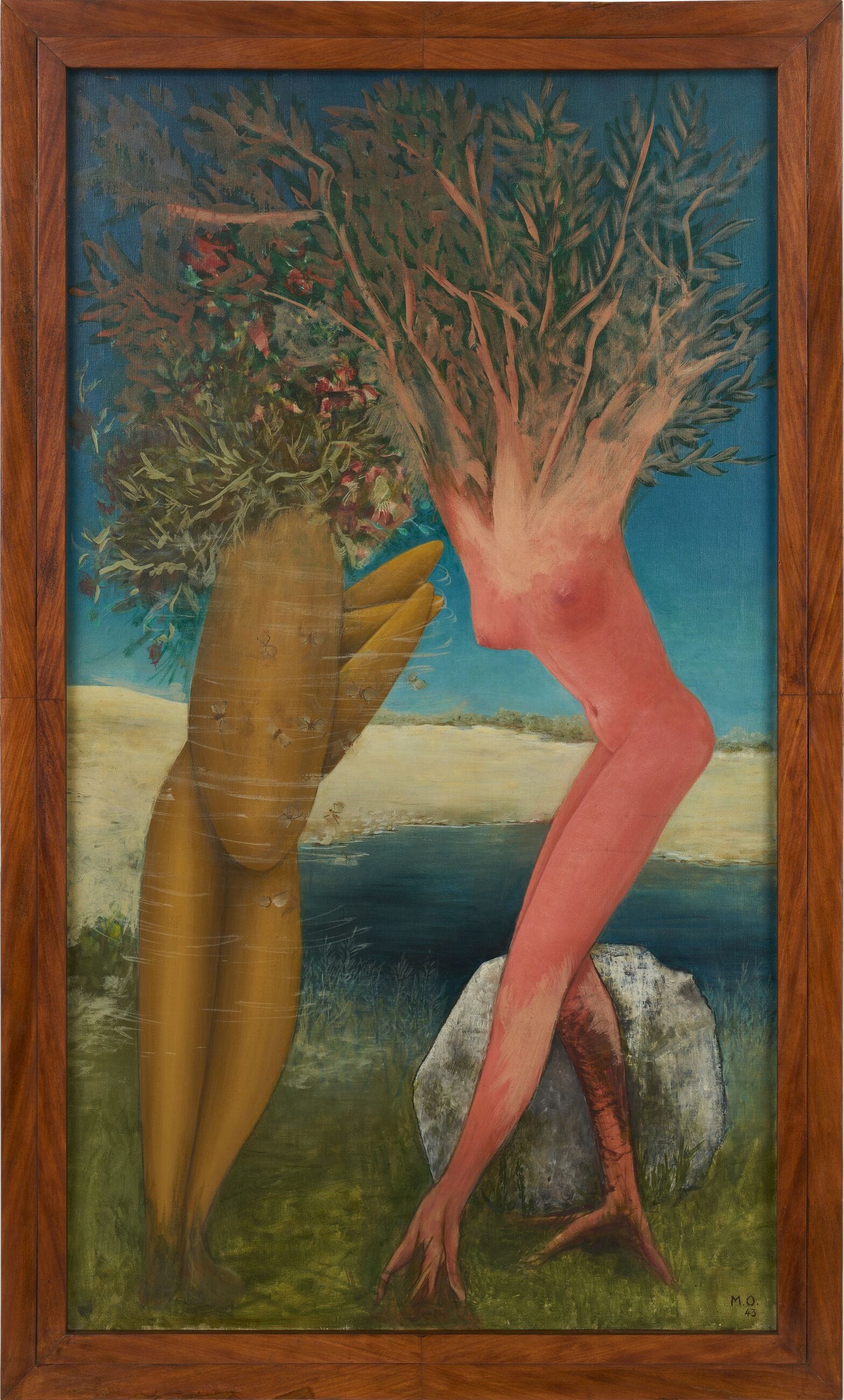

Meret Oppenheim to her niece, Lisa Wegner. On Katy Hessel’s Great Women Artists podcast, Lisa relates the story: “We were both brushing our teeth in Casa Costanza, she was there for the summer and I came up from Milano. I was about 30. She asked me, ‘What about children, do you want children?’ I said, ‘No, not really.’ She goes, ‘Good, because you can be a perfect and total and complete woman without kids.’ To me that was a real eye opener.” Meret Oppenheim’s work is on view at Hauser & Wirth in Basel. I picked her painting of the legend of Daphne and Apollo because, canonically, only Daphne turns into a laurel tree; in Meret’s version, Apollo enjoys the same fate.

Field Trip: “An Exhibition for Children (and Other People)”

Field Trip is another new regular column reporting on exhibitions and institutions. Some of them will be in-person visits, but I did not make it to Germany this week.

This is an exhibition I was really hoping to take a child to but, as it is closing on 6 July at the Kunstverein Hannover and I am still hard at work in sunny Taipei on 1 July, I have decided to bite the bullet and report on it in absentia. The reason I wanted to bring a child along was to test its premise. It is, after all, what it says on the box: “an exhibition for children.” And other people. But, curated by the artist Jeremy Deller, it also consists almost entirely of pretty canonical post-conceptual art. Is this a compelling proposition for children (and other people) who are used to being pandered to in more direct and more directly interactive ways? I hope so. I guess.

Obviously museums today have many reasons for wanting to appeal to children. It is summer holiday. We want to get them used to coming to museums from a young age. Also, many adults have the intellectual capabilities of children, and keeping things child-friendly sidesteps some of the thornier political issues that artists are otherwise wont to grapple with. So are playful videos and gestures at age-appropriate humor really fun for children? Or would everyone rather stay home?

The exhibitions open with the classic Fischli and Weiss video The Way Things Go (Der Lauf der Dinge) (1987), their studio Rube Goldberg machine, and then opens toward physical interaction with chalkboards from Rivane Neuenschwander that invite visitors to fill in comic panels, non-prescriptive play sculptures by Temitayo Ogunbiyi, a wall by Roman Ondak against which visitors can record their heights, and room in which visitors can draw from life a weird sculpture-as-model by David Shrigley. There is also a video by Eva Rothschild called Boys and Sculpture (2012) in which her work is played with and deconstructed, as well as one of Francis Alÿs’s many videos documenting the games of children around the world. Ryan Gander fills one room with balls bearing poetic questions asked by children (recalling the Sarah Manguso book we looked at previously), and inserts a mouse with his daughter’s voice into the wall of another.

In what starts to seem like a parody of playfulness at the end of the exhibition, Lara Favaretto hangs a long whip studded with jingle bells on the wall, and recorded people talking about “naivete and consciousness” for publication at a later date. In the same room, visitors find Jeremy Deller’s video Has the World Changed or Have I Changed? (2000), ostensibly, the raison d’etre of this show—to celebrate the quarter-century anniversary of his invitation of a clown to roam the fairgrounds of Expo 2000.

Book Report: Bring No Clothes

Book Report is a regular column that reads books for, by, and about artist parents.

I did not intend for this project to become so focused on Bloomsbury. To be honest I don’t really know how it happened. I don’t really even like the work that much. In theory I could pick up any book off the shelf, there are so many in the queue, and give it a reading about art, biography, and domesticity. There is something in Bloomsbury, however, that keeps bringing me back to it. I picked up this copy of Charlie Porter’s Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion in Paris in January and read it soon after. Charlie’s title is a quotation of the language that Virginia Woolf used to invite guests coming to stay: Bring no clothes. We do not dress for dinner.

Perched between fashion and art, Charlie Porter is a brilliant writer on all of this stuff, and employs no small amount of the biographical interpolation, the productive misreadings between the lines, that make this kind of historical work fun. The very first chapter opens by dangling one of these mysteries, the question of an oversized dress that Virginia wore for a Vogue photoshoot, understood to be her mother’s dress. Charlie doesn’t buy it, labeling it NHMD (not her mother’s dress), and 300 pages later floats a theory that Virginia and Ottoline Morrell were lovers, that it was Ottoline’s dress that Virginia was wearing (the stylistic evidence adds up), that “queer partners can wear the same garments to manifest their love.”

In between we get a torrent of photographs of the crew at Charleston and, in particular, at Garsington Manor, including the legendary image of Carrington hanging nude from a statue that made a dramatic appearance in This Dark Country. The boxy suits, the tailoring, the nudity, the hand-sewn garments, it all presents such an irresistible texture that Charlie designs and crafts a bit of his own rave wear throughout the course of his research. His eye for the lived detail is pure joy, from the dimensions of the wardrobes at Charleston to lines from Ottoline’s diary to the coded poses of John Maynard Keynes in the garden.

Links: (m)Othercare, Lifelong Kindergarten, and Living with Friends

“The Mother Is Dead, Long Live (m)Othercare: Care as Alterity, an Introduction” in e-flux Journal

iLiana Fokianaki is one of the leading voices in the art world on the politics of care, and this journal article, the first of two, proposes several institutional pathways for resisting “the new wave of far-right racist patriarchy.”

Lifelong Kindergarten at MIT

This research group at MIT develops technologies and communities in creative learning experiences. I’ve gotten really interested in how people are thinking of early years education in the context of AI, particularly as my daughter seems more interested in using it to replace or supplement social connection than anything else. (The ethical dimension over plagiarism, reading, and focus seems comparatively more straightforward.)

“A Grand Experiment in Parenthood and Friendship” in The Atlantic

A look at adults with young families making intentional co-housing choices to live with or near friends. I think this is a brilliant idea and also think it makes incredible amounts of sense to have children on the same timeline as close friends, especially if it isn’t possible to live near family.

Learnings from Adrian Wong

Learnings is a new regular column that digests some of the lessons from the Lives of the Artists column. Lives of the Artists will run on a monthly basis until the fall, alternating with newsletters in today’s format.

Now that I’ve had a couple weeks to let my conversation with Adrian Wong percolate, I wanted to synthesize a little bit of what we talked about. The top takeaway for me is still that line I bolded in the last little bit about how what he wants his daughter to learn from his artistic practice is that she can change the world around her. I think this is something that we can all learn from artists. One of the talks that I’ve given over and over again in the past few years looks at “lifeworks,” the practices of artists who have an overarching way of being in the world. My argument is always that we should approach the details of our lives with the intentionality with which an artist approaches a project—so much falls into place with a bit of thoughtful consideration. In the positive psychology literature there is a line of thinking that children need to grow up with a bit of entitlement, not in believing that they are entitled to more than their peers, but that they are entitled to agency as children in a world of adults. Assertiveness, self-confidence, the right to be heard. This is something that does not come naturally to me as a person, and something I learned about too late to properly convey to my daughter, but it’s a lesson I think we need to keep working on.

The next issue of Lives of the Artists will run on 16 July with Jin Meyerson in anticipation of his solo exhibition “Safe Space” opening at Perrotin in LA.

And with that—may your road home be a long one.