Robin Peckham

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Lives of the Artists is a regular monthly interview column profiling contemporary artists, asking them to share the connections between their home lives and studio practices.

I am thrilled to share this conversation with Adrian Wong, someone who I have intense respect for as an artist, intellectual, and father. Adrian and I met in Hong Kong 15 years ago and have worked on a number of exhibitions, commissions, and other projects together. Also, our daughters once tried to smuggle a feral cat from the Saronic Gulf to Heathrow. This is the first half of our conversation, focusing on a body of video work in which Adrian traces stories of his family through Hong Kong.

Let’s start with your childhood. How did you find your way to art?

Adrian Wong: I went to school with a bunch of tech-focused, entrepreneurial people and started studying a lot of math and physics, but I got interested in the thinking behind these things so I switched to psychology and product design. I was in a master’s program in developmental psychology and got interested in art during my thesis research, when I had to spend a lot of time interacting with kids in an orphanage in Vanadzor, Armenia. The ruse I came up with was to pretend to be an art teacher. When I got back, I kept the art up and ended up with enough credits to get a degree in art alongside my work in psychology, and then when it was time to transition to a PhD I took a shot in the dark and applied for an MFA instead.

Looking at your practice, I see a few different stages, and one of them is this early interest in early childhood that comes out of your psychological research. And then as soon as you establish your studio in Hong Kong, the practice becomes very relational, and you’re working in collaboration with other people.

One of the things that led me away from the social sciences was the realization that the deeper I got into what I was doing and the better I got at what I was doing, the narrower my zone of activity became. If I started to pull things from outside, all of that was cut out by the time my research was approved. It was a complete accident that I came to Hong Kong, but I got really interested in a lot of different things, all of which were outside my area of expertise. The studio became a place where I could give myself license to explore things, to do the kinds of research that I found personally interesting, just to see what happened.

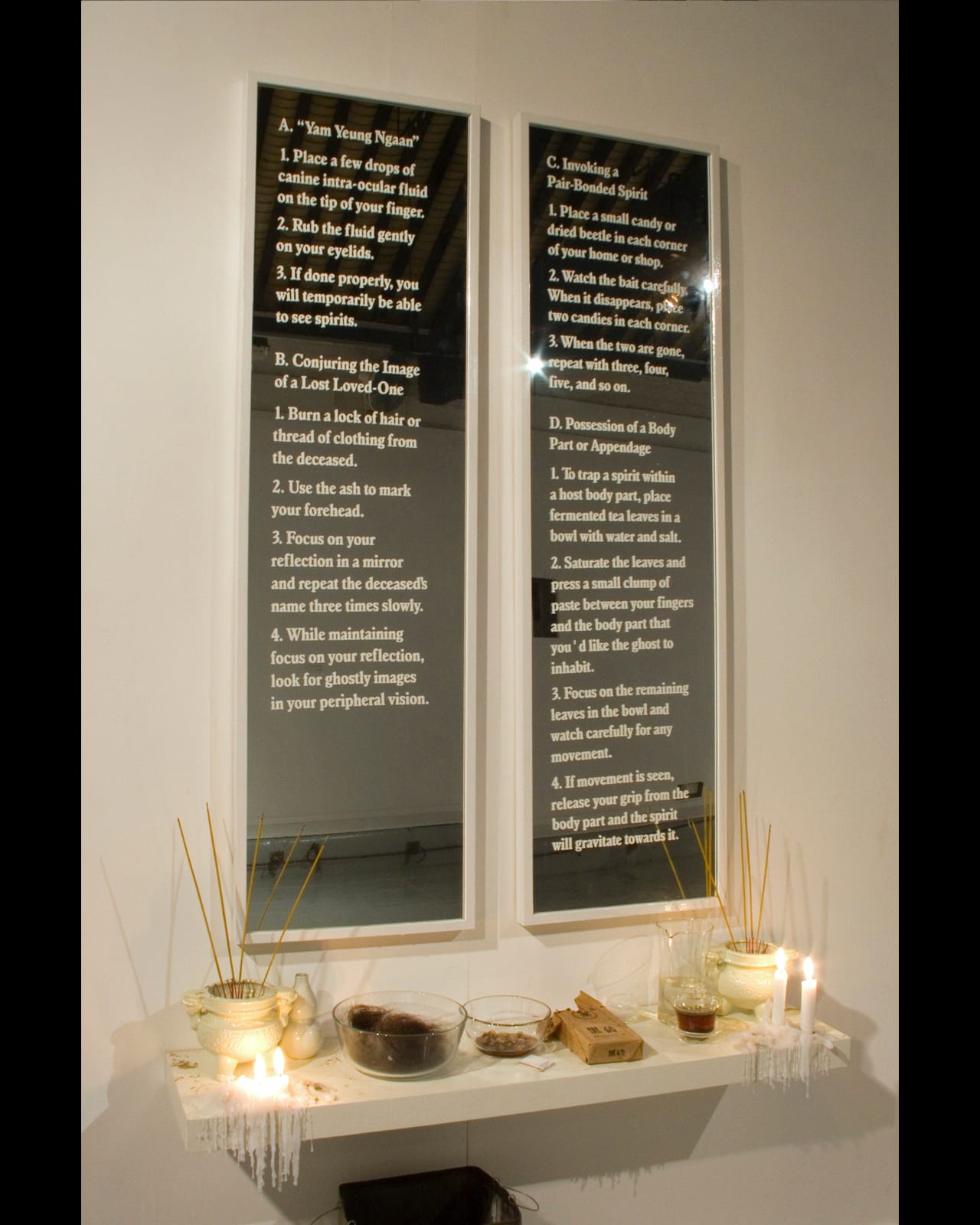

My first studio was awesome. It was a nightmarish wreck of a place. It was 4000 square feet, so in a space that big I could take the contents of my mind and allocate them real estate. There were whole sections of the studio dedicated to different branches of the practice, and they intermixed in space. I got really into vernacular architecture in Hong Kong. I was looking at local superstitions, doing a lot of stuff on ghosts. I had a section of the studio where I had set up a bunch of apparatuses to invoke spirits to come commune with me. There was a drum kit. It was the first moment where I was able to step outside of an academic context, to completely throw myself into thinking about my environment and process the world that I was living in.

And in a way you were using your practice to investigate or connect with your family history in Hong Kong, right?

I met someone in grad school who was on a teaching fellowship at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, so I just accidentally ended up in the place where my mother and father were born. My mother and father were both estranged from their families to the extent that I didn’t really know where I came from. My father’s side was a complete void for me, apart from a few comments that were made over the course of my childhood. I was partially raised by his mother, who never spoke about Hong Kong. It wasn’t until I got into that research that I realized how deep my roots were. For that first project I set out to rediscover a specific person that came up in my father’s family. This was my grandfather’s youngest brother, Calvin Wong, who was a Dick Clark-esque TV presenter in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. I was able to track him down, and found out that his son, my uncle Harry, was a celebrity magician in the 80s and 90s, so we ended up doing some work together. I art directed children’s theater as a side gig for a while for him, and acted in some of his productions.

Can you introduce the Sang Yat Fai Lok (2008) project?

That was the first proper show I had in Hong Kong. It was a two-person show at Para/Site, one of the first few shows that Tobias Berger put together when he came in. Calvin Wong had a TV program that aired for two decades in Hong Kong, and I thought it was a really interesting concept. It’s called Happy Birthday, and every Saturday he found a kid celebrating their birthday, and then threw them whatever kind of party they wanted. There would be some very surreal, strange requests, like a kid who loved ham so much that he wanted to have a ham party. And they would recruit a studio audience to play out this kid’s fantasy. When I finally tracked down my great-uncle Calvin, I found out that the show was never recorded—it was live from the studio to TVs in people’s homes and public parks. So I recreated an episode of the show, using it as a structure through which I could reinvestigate my connection to my family, with details drawn from what I learned about my father’s childhood, my grandfather’s childhood, the show and its role in my family.

Recently you’ve returned to researching your Hong Kong family with a project that loomed large in my understanding of your practice because I heard you talk about it for so many years. Can you describe your grandmother and how she entered your work?

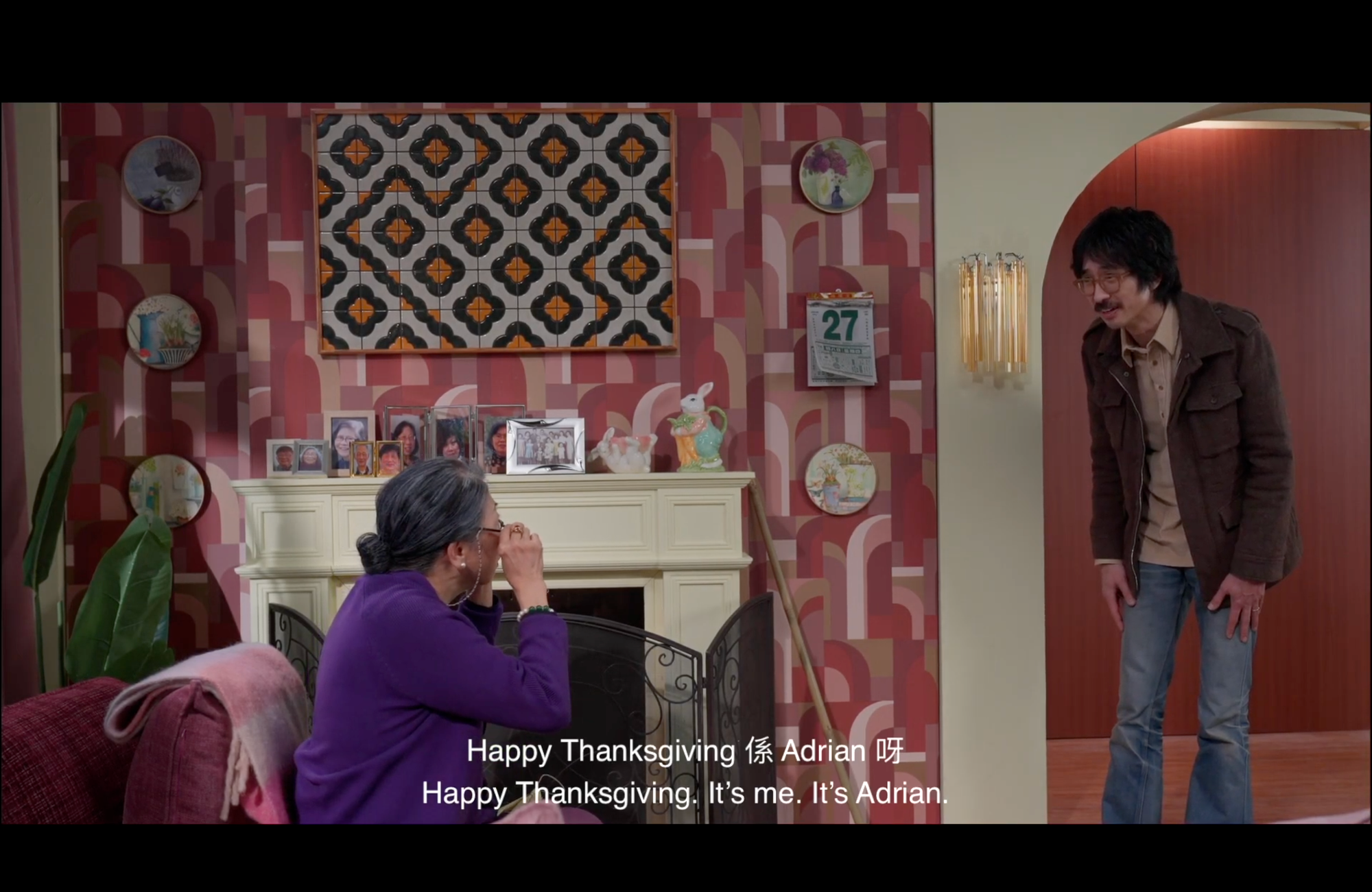

I grew up in Park Forest, Illinois, which was the pinnacle of postwar suburbia. My grandmother lived most of her life in extraordinary privilege. My grandfather’s family fortune was vast. She gave birth 16 times. My mother was the 16th of those. Eight were viable, all eight are still alive. My mother’s oldest brother, my uncle Joseph, is over 100. My mom is 73. Her mother was not a traditional mother. I interviewed a lot of them for this project, and they barely knew her. They barely saw her. My mom has very few childhood memories of her mother. She was a socialite and spent most of her time throwing parties. My grandfather died relatively young. My grandmother did not have any formal education and got the keys to the kingdom after he passed, and spent decades burning through the family fortune. My mother’s siblings all expected some kind of inheritance, but she lived a very, very long time and ran out of money. My understanding is that she came to the United States because she couldn’t sustain herself, so she ended up landing with our family.

She took over the lower floor of our house and didn’t really want anything to do with us. She routinely wore these beautiful gowns and cheongsam, full face of makeup every day, and drifted around hardly acknowledging us, like a ghost living in our house. But she was fully immersed in daytime television, watching American soap operas religiously all day long. When she passed away she left a rack of composition notebooks, where she had kept notes on the soaps. For a long time, given the work that I was doing, I thought that if I had the opportunity to translate her notes, I would have some kind of outline of her version of the stories that she saw, and I thought I could get into that space and create a surrealistic soap opera based on her notes as a way of getting to know her better.

Unfortunately, when I was able to go back into those notes and have them translated, it was all gobbledygook. The project that I showed at Oil Street this spring mostly uses my recollections of that period of her life, but also tons of interviews with her kids, trying to get the bottom of what her life experience was like. Much like Sang Yat Fai Lok for my father’s side of the family, it became a loose retelling of my grandmother’s life from birth to affluence to her later years living with our family in suburban Illinois.

You’ve shown this in Hong Kong in a reconstruction of the sets.

AW: I replicated the sets, which were huge. I built four sets, with the help of an incredibly talented scenic designer, G Tsui. One set was a daipaidong, which is where she was first seen by my grandfather. My grandmother was from a lower-class family in Zhuhai, and while she was out buying the fabric for her annual new clothes at Chinese New Year, she was spotted by my grandfather, a little prince who saw her and said, “I want to marry her.” He picked her out from the crowd and arranged for a proposal to be delivered to her home. She was plucked from her family and never saw them again. There was a first wife from a notable family who was immediately demoted to maid. She worked administratively for the family and supervised the maids and drivers. My grandmother didn’t know she was actually his first wife until he died. Of all of the eight living children, not a single one of them could remember her name. Then there was a recreation of what her childhood home might have looked like, and finally a dual set split between my grandmother’s home in Hong Kong and our home in Chicago.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Shorts is a regular column with links and commentary on family culture.

Juergen Teller (Talk Art)

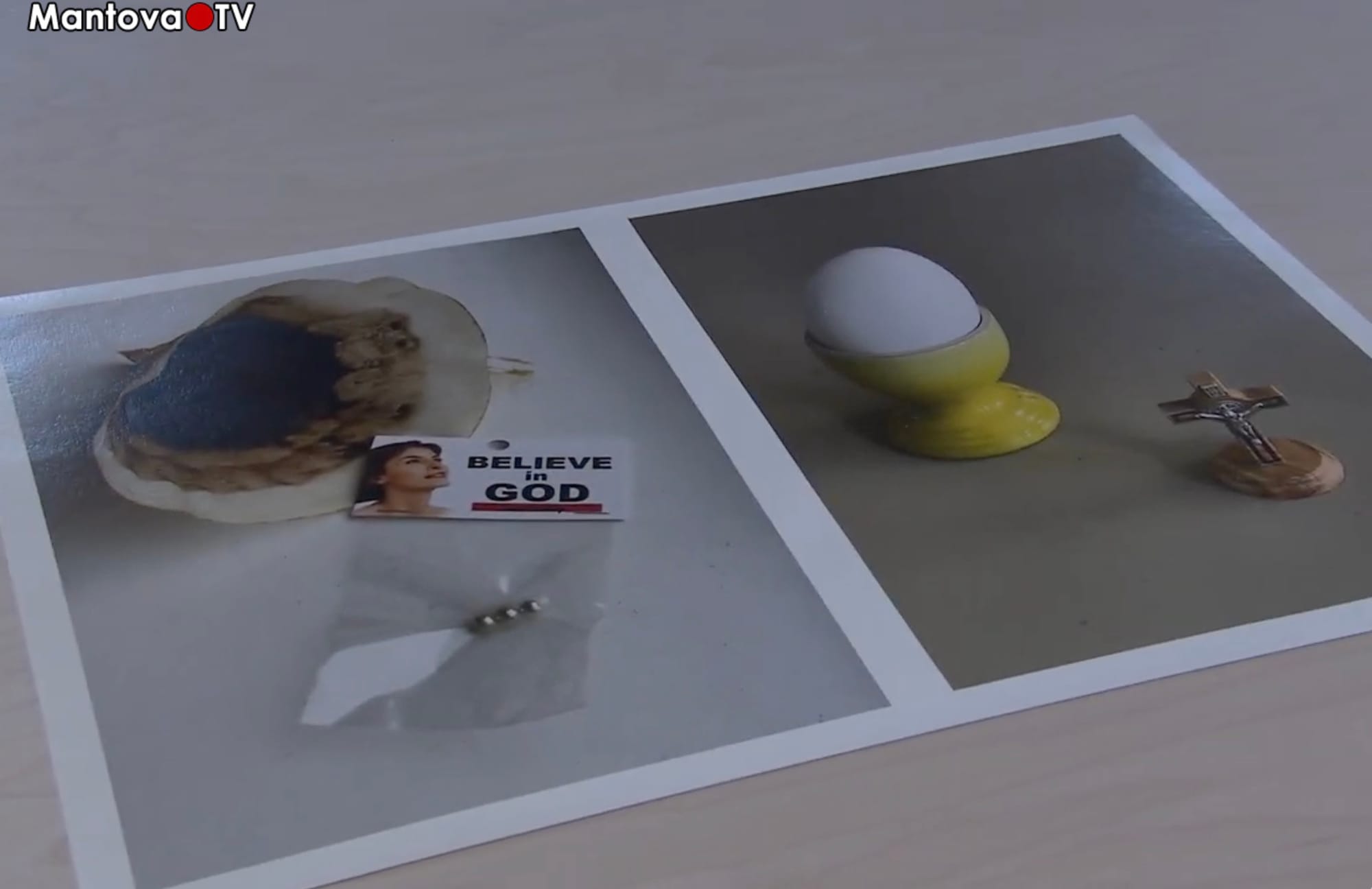

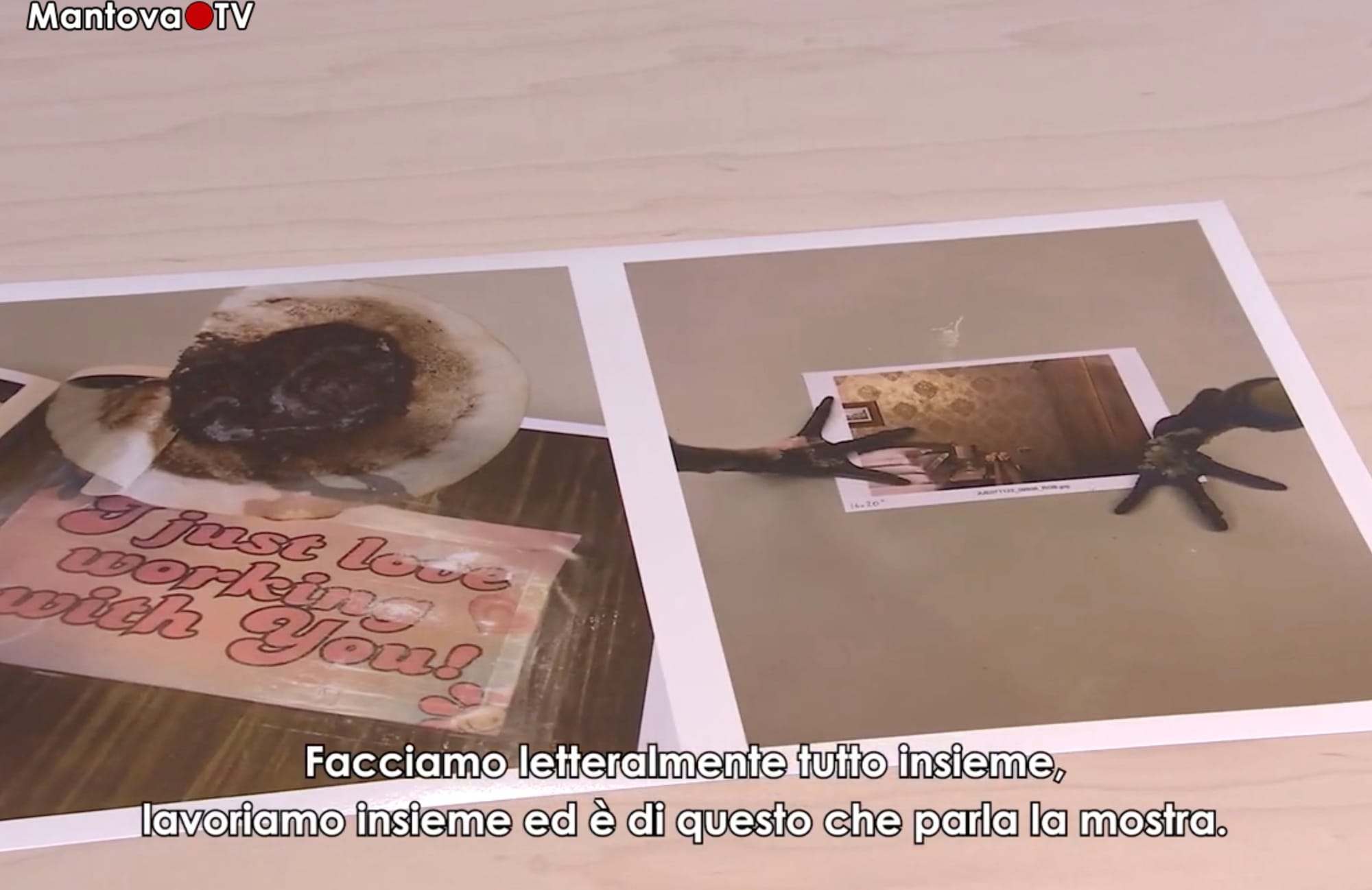

On one of the millions of artist interview podcasts I listened to last week, Juergen Teller introduced his summer exhibition “7 ½” at the Galleria degli Antichi and the Palazzo del Giardino in Sabbioneta. The show is titled after the duration to date of his relationship with Dovile Drizyte, who has become a creative collaborator as well as a romantic partner. Last year they released a beautiful Steidl book together called The Myth consisting of 97 photographs of Dovile posed with her legs in the air in allusion to the idea that the pose improves the odds of conception, one in each room of the Grand Hotel Villa Serbelloni on Lake Como. Juergen also described a new project in which he photographs the pourover coffee he has made for Dovile each morning for the last seven and a half years, then photographs the environment around the coffee. This series caught my imagination for its tenderness and simplicity, but I haven’t managed to find any images yet, save these screengrabs I’ve borrowed from a report on the exhibition by Mantova TV.

I always enjoy the contrast between the high gloss of commercial fashion photography and the offhanded nature of the personal and art images that fashion photographers take. Juergen Teller has never been afraid to put his children in front of the camera: Iggy, his daughter with Dovile, is the star of this Document Journal portfolio recreating some of his iconic shots while Lola, his eldest daughter with Venetia Scott, was a part of some of these shoots the first time around. Ed, his middle son with Sadie Coles, is the heart of the 2006 photobook Ed in Japan. For his retrospective at the Grand Palais Ephémère a year and a half ago, Teller put together an eerie triptych: on the left, a photograph of himself as a baby taken by his father; in the middle, an enlarged copy of a newspaper notice of his father’s death, “Mit Auto den Freitod gesucht?” (“Suicide by car?”); at right, a photograph of his mother hamming it up with a taxidermied alligator.

The exhibition was titled “I Need to Live” in reference to the ongoing choice to not follow his father. In 2003, Teller shot a series of photographs at his father’s grave. In one, Mother and Father, his mother faces the camera, partially crouched down, arms outstretched like a keeper in front of a goal. In another, Father and Son, Teller himself holds a lit cigarette and a bottle of beer, one foot resting on a football, completely nude.

Yiyun Li (New Yorker)

I did not particularly want this to become a theme for this week, but Yiyun Li’s writing on her sons’ suicide gives us some of the most eloquent lines there could be on what it means to choose to live, and what it means to create the conditions to allow others to carry on with their own choices in life, whether they choose to live or not:

If I train my mind on the happy moments, the framework for living seems sturdy enough. And yet it is not an indestructible shelter from catastrophes. A mother dedicating herself to the framework for living is like a ship-builder building a vessel, not asking whether the voyage is to be through calm seas or tempests, not pondering whether there will be a tomorrow or not.

Proust (Personal Canon)

In her newsletter, Celine Nguyen quotes Roger Shattuck on the meaning of Proust: it’s about “human beings faced with the appalling responsibility of living our lives.” The whole essay is wonderful and very much worth reading.

Art Collecting with Kids (Art Basel)

A collection of really cute photographs of collectors’ children tagging along to studio visits and helping to install artwork in vacation homes.

Artist Homes (The Guardian)

Katy Hessel writes on visiting artist homes, and understanding domestic space as an environment every bit as important as the studio to the conception and production of the work. She mentions artists we have looked at here: “Ruth Asawa looped her wire sculptures on the kitchen table surrounded by her six children,” and “for Bourgeois, her house—both a prison and site of freedom—was her muse.” I think this would be a great topic for a book.

Sarah Manguso (LARB)

I haven’t yet had a chance to read Sarah Manguso’s new book Questions without Answers, which collects replies to “What’s the best question a kid ever asked you?”. This short interview touches on the book itself as well as her philosophy of education, and includes a couple gems:

Before I was a mother, I thought of my life as my very own masculine-coded hero’s journey. Now I raise my kid and I write, and I find both of those practices so much more interesting (and more heroic?) than the life I wanted when I was young.

And for this week, I’ll end with this:

There’s a huge overlap between making art and raising a child—and there’s an overlap between making art and being a child.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Projections is a regular column on films that touch on living in a creative family.

We tend to look on with something less than generosity when people make art too directly or too biographically about members of their family. Earlier this week Kaitlin Phillips described Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold as “pure hagiography by an underemployed nephew.” (I don’t know Griffin Dunne as a director, but he played an excellent Sylvere Lotringer in I Love Dick and I’m only slightly embarrassed to say I spent an inordinate amount of time with him in This Is Us.) Perhaps we should not expect critical engagement with the work from these kinds of projects. What we watch for instead is the anecdote of intimacy, the tendency of the lesser-known relative to share trivial moments of family life—celebrities have them, intellectual giants have them—in a way that somehow illuminates our own reading of their work. Our relationship with the work, after all, is our own. The work does not belong to us, the person certainly does not belong to us, but the way it lives with us, the experience it creates in our lives—that belongs to us and to us alone.

Tomas Koolhaas shot REM (2016) over the course of three years during which he followed his father through the far-flung offices of OMA, onto construction sites and into completed projects, and to the opening of the Venice Biennale the year that Rem curated it. Kaitlin’s criticism holds here, too: what we see is pretty anodyne. It can’t be easy to shoot your father the way you see him, the way you want to see him, the way he wants you to see him, the way you want him to see you seeing him, and the way he wants the world to see him all at the same time. As viewers, we get some well-considered quotes on architecture and urbanism from a great designer looking back on his career and beginning to think about the end of an era. He looks at the grand sweep of OMA over 50 years from New York to China and now to the Middle East, with Europe inevitably as a home base that acts as foil to whatever else he is working on. He describes his practice as a willingness to engage with impure things and look for the rigor within them.

In the opening shot, young people skateboard in front of Casa da Música in Porto, where my father lives. The building is perhaps more iconic as a skate spot than as a music venue. Later on in the documentary, intertitles will relate: “A building has at least two lives—the one imagined by its maker and the life it lives afterward—and they are never the same.” Like a child, a building has to live out its own independent life. This becomes increasingly evident as Rem and Tomas visit completed OMA buildings: they interview the unhoused about the formal qualities of the Seattle Central Library, then meet with the daughter of Jean-François Lemoine, the late publisher for whom the Maison à Bordeaux was originally designed. Full of custom mechanisms to enable the partially paralyzed man to live an active life, the house is a bit ghostly without him to activate it; we watch Rem stare into space as he moves up and down on mechanized platforms while doors open and close around him. The challenge, says the daughter Lemoine, is to give new meaning to all of these automations now that her father is gone.

There is an interesting attention to the language of the body. One scene focuses on Rem’s daily swimming practice, and the expectant and open state of mind that results after he has had his swim. In another, he talks about observing the workers on the various construction sites he visits, noting not only cultural differences in how they work individually or together but also differences in energy and morale. Aware of the criticism of starchitects, of the fantasy of globe-trotting designers plopping down their weird signature forms wherever they go, Rem says that it is not that he is interested in making the same thing everywhere, but rather that he has been allowed to do different things everywhere. My friend Jacob Dreyer wrote recently in Artforum to question the logic of OMA in our new political era: “Now our governments are more radical than our artists, who tag along behind asking the government to be careful, to consider unintended consequences.” I feel that the utopian logic that Jacob ascribes to OMA’s past work is inaccurate and ahistorical; the point has always been to engage with messy realities and, if anything, the mess to be engaged with now is only proliferating.

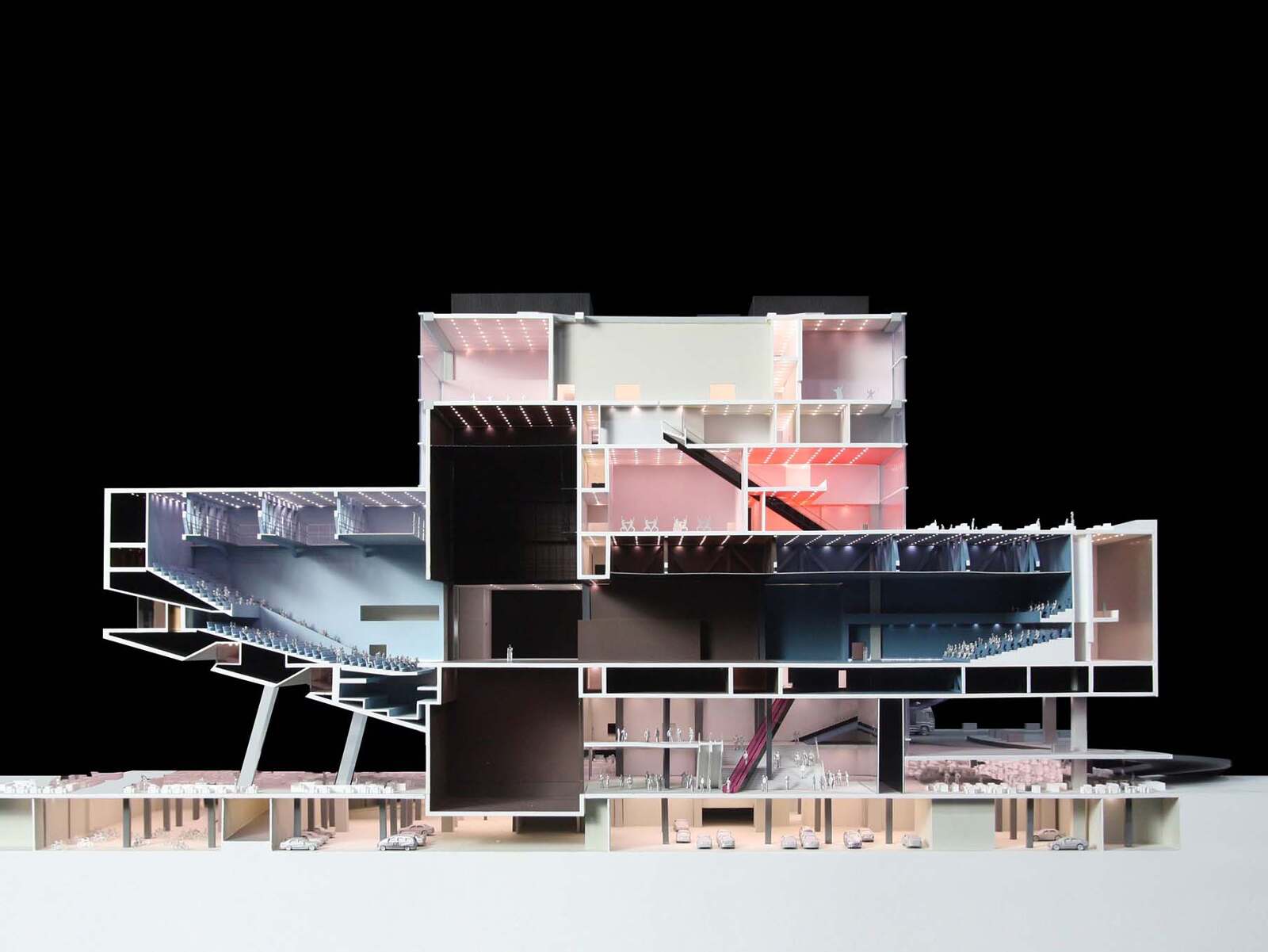

Sketches and models for TPAC by Petra Blaisse, with the combined theater space visible at right

These markers ring true to my experience of OMA projects: they embrace the impure, they celebrate the rigor of internal logic, they are more platform than stylistic statement, and they create possibilities for unexpected forms of movement. Later this week I will be back at TPAC, affectionately nicknamed the egg-on-tofu, for a performance of Łukasz Twarkowski’s Respublika. This production will, for the first time, open up two of TPAC’s three theaters to each other, creating an unexpected mega-space that has taken quite a bit of time and engineering to realize. A couple months ago, when I toured the building with Hans Ulrich Obrist and Chiaju Lin, who directed the project on behalf of OMA, Rem phoned in with excitement to hear our feedback. Living in Beijing during the construction of the CCTV tower, I heard a lot about the circularity of media production, and how the design of the building would allow for a public loop providing visibility into the circulation of the image. That being Beijing, a lot of the transparency was eventually dropped from the program. But in Taipei, TPAC has the Publicloooooop, a route that runs through the building offering glimpses of backstage production facilities as well as views of the surrounding neighborhood. Like buildings themselves—like children—ideas have afterlives of their own, popping up in unexpected places.

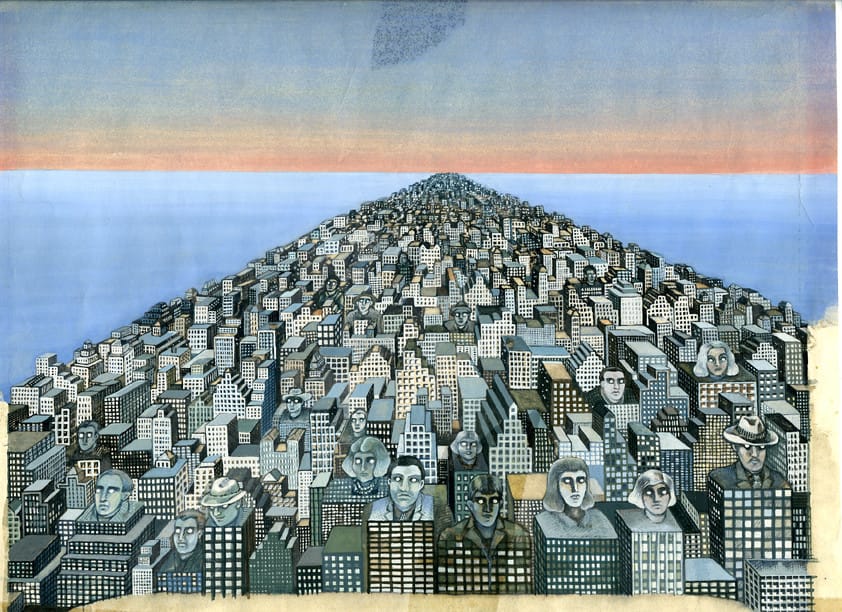

Work by Madelon Vriesendorp

In Venice for the Biennale, Rem speaks of a full-circle moment to see both of his children engaged with his professional life and with the creative world. Aside from Tomas, director of the documentary, Charlie is a photographer and artist. Their mother is Madelon Vriesendorp, a co-founder of OMA and the brilliant artist behind many of the defining images of the OMA universe, like Flagrant délit (1975), seen on the cover of Delirious New York. Madelon and Rem divorced in 2012. Rem’s partner Petra Blaisse has collaborated on many OMA projects through her firm Inside Outside, including both the landscape architecture and interior concepts for TPAC. Rem D. Koolhaas, nephew of Rem, is the founder, with Galahad Clark, of footwear brand United Nude.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about the intersection of art and life. Editor's Notes is a regular column introducing issues, themes, and frameworks from a personal perspective.

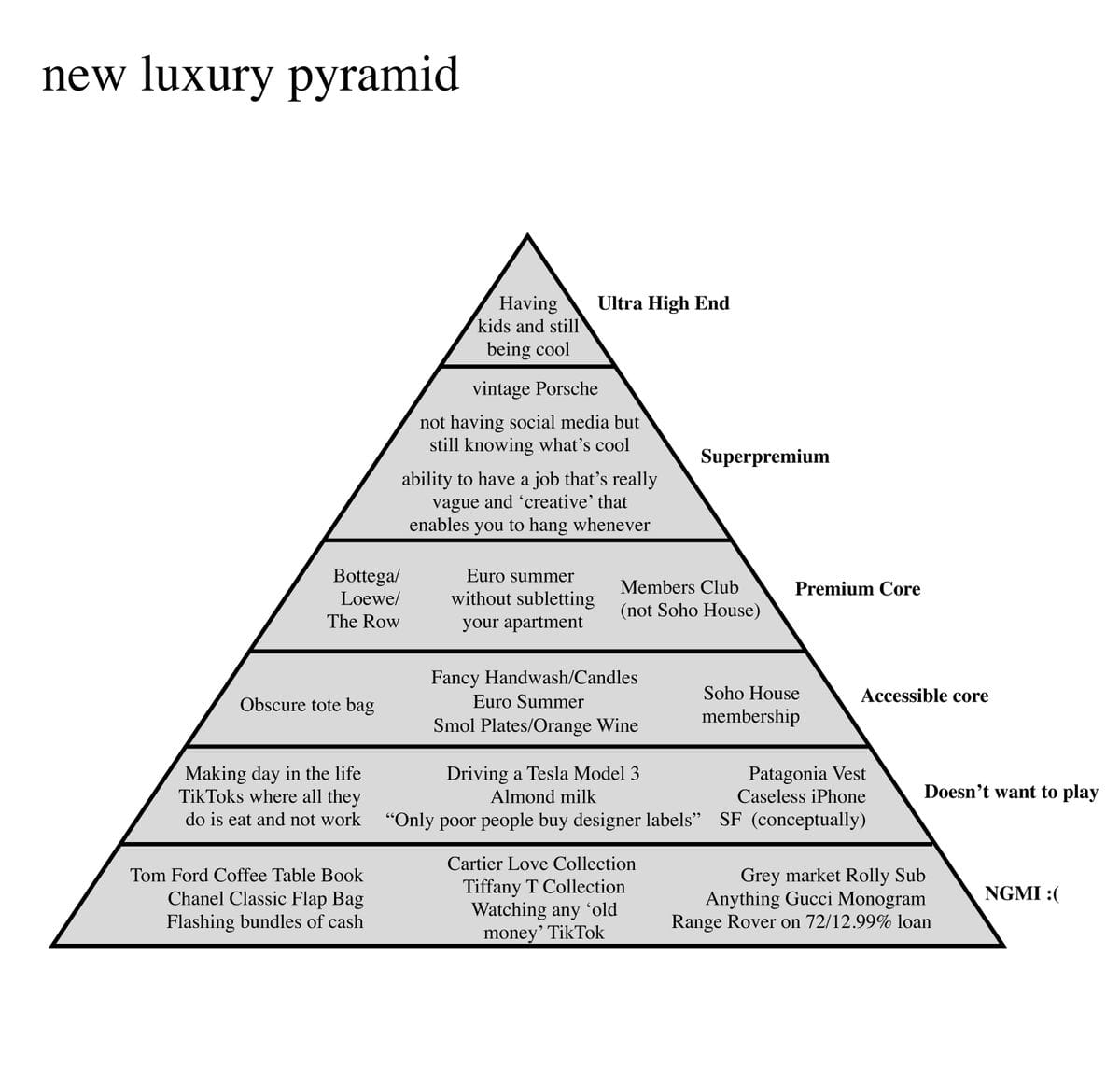

In the New Luxury Pyramid, the Ultra High End is defined by having kids and still being cool.

This graphic made the rounds in 2024 and, given my vocational interests in core values, came back to me over and over again. It comes from Edmond Lau, the strategist/ designer/ meme guy who mostly circulates on LinkedIn (which itself might make an entry somewhere in the diagram). Lau offers his own explanation:

The New Luxury Pyramid: In the time of the 'Oat Milk Elite', status signifiers can be difficult to decode. What once might have been a universal signal of wealth like a Rolex or a Chanel Bag, now can under certain circumstances instead ironically communicate the lack thereof. These days, it seems like we prefer signs that are harder to fake. Taking a photo with a Birkin? Easy. Maintaining your yuppie deluxe lifestyle with two kids and a mortgage? A little harder. Think caseless iPhones, 10.30am fitness classes, not having roommates.

I see his point about how these things signify an economic and social elite. Kids are expensive, but even more expensive is the bandwidth to continue living on one’s own terms while also caring for kids. The idea of status signaling is not so interesting for me, however. What I’m interested in is how this is framed as luxury, because that’s what this life is: it’s pure luxury. I’ve worked with a lot of luxury brands throughout my career, first in publishing and more recently in art fairs. What’s fascinating to me about their events and activations and communications with their clients in general is that so little of it is about the product. Much more of it is about the experience, the intangibles around everything. Luxury is care, attention, and intention.

Or there’s Derek Guy:

the older i get, the more i realize that the most luxurious thing is being able to live in a walkable city. wearing a nice little outfit and walking 15 mins to buy just enough groceries for a single dinner will make you feel like Mrs. Dalloway going to the market

— derek guy (@dieworkwear) June 30, 2022

This line hits hard because I am so fond of referring to myself as a “Mrs.-Dalloway-said-she-would-buy-the-flowers-herself” kind of guy. Lauren Sands writes on her Substack that selling luxury involves defining what luxury means to you and then figuring out who else would define that as a luxury. She offers a list of her favorite luxuries:

A heated toilet seat (bonus if it automatically raises) / Jewelry made by a friend / A piece of clothing I have had for years and worn innumerable times / Reliable high-quality healthcare / Living amongst things that reflect my style / Site-specific artwork / TIME / Reading / A vintage coat that I spent months tracking down on eBay / Friends that I have had since childhood / A long lunch with an artist I admire / Happy children / A pair of shoes that look good with almost any outfit / A hand massage from my husband as I fall asleep / Help (with children, work, carrying a heavy bag, really anything) / Writing a substack newsletter / Hosting a dinner party / The right kind of vacation / A handmade piece of pottery / An obscure watch that is hard to find

Having kids and still being cool. The luxury in the lifestyle I’m talking about, I think, comes in through the excess of meaning. Working in art and culture it is easy, too easy, to feel fulfilled—to feel that we are creating something of value to the human experience. (And I will insist to the death that this is a feeling that everyone deserves, and should actively seek out.) And raising a child, it probably goes without saying, comes with an inbuilt sense of purpose, one that I would extend to caring for a loved one with intentionality regardless of whether he or she is a child, a parent, a romantic partner, or a dear friend. To have both at once—it’s often overwhelming.

This week I read Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico and laughed at myself for how accurately some of the signifiers of the millennial lifestyle he’s skewering describe my choices in furnishings, hobbies, and vacations. I haven’t read Perec’s Things but somehow suspect I would feel equally called out in those pages. And yet as ennui kicks in for our protagonists I can’t help therapizing them just a little bit. They aren’t able to find quite enough meaning in their work, but only because they aren’t really trying to. And they aren’t able to find it in their family configuration, but only because they haven’t looked it in the eye.

Between the New Luxury Pyramid and these meditations on lifestyle and meaning, there is clearly a difference between working for meaning and working for sustenance. We lead lives of wild privilege. To do work because it is a pleasure, to put something out into the world. Luxury.

With the conclusion of my six-part essay on “Real Paintings and Fictional Painters,” I hope I have shared a bit of the motivations and inspirations behind Nostos. Moving forward, I’ll continue to write once a week on Wednesdays. On a regular rotation, I’ll share letters from the culture: the books I’m reading, movies I’m watching, exhibitions I’m seeing, links I’m sharing. Once a month, I’ll also share a conversation with an artist or creative focused on how they position their professional practice in relation to their personal lives, particularly their families and friends. This will be the heart of this newsletter going forward, and over time will constitute an archive in support of what it’s all about: having kids and making culture is indeed the ultimate luxury.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Essays is an occasional column that teases out in greater depth how family life appears in culture.

It’s something that is repeated often about the occasionally codependent relationships artists have with their work: they couldn’t have lived otherwise. They couldn’t have lived, otherwise. I have no doubt that this is true, that artistic practice plays a constructive or even therapeutic role—that creativity and making and putting something out into the world is one of the things that makes life worth living. But it also seems to be trotted out a bit too often as an excuse for the bad behavior of artists, as if the artistic impulse were in control of their life decisions. This impulse, certainly, is a powerful thing. Over time my interest in what art can do has drifted into the camp of the pro-social, into forms of practice that are inherently social and relational. We want art to shatter our illusions, to break things, to fail spectacularly and in doing so show us the limits of what we are able to imagine, and there are ways for this revolutionary, violent impulse to be channeled into the practice. We have spent a lot of time with Alice Neel, whose two sons had an ambivalent relationship with their mother’s practice and bohemian lifestyle and took their lives in another direction. To conclude this series, I want to turn to the work of Kim Lim, a sculptor a generation or so younger than Neel whose radical work was intertwined with a life of love and cultivation, and whose two sons carry on her legacy both directly and indirectly, continuing to advocate for her profile by shepherding her estate while also developing their own pro-social creative practices. She said of the configuration of their relationship in 1966:

I virtually ceased to be an artist when the children were born and while I felt they needed my full attention. I don’t regret one moment of that time, but since one is now at school, and the other will soon be going, I have returned to art. Of course, it’s different being a woman—but it needn’t be a disadvantage. What one needs is tenacity to keep on working-to sculpture without denying domesticity.

This winter I had the immense pleasure of viewing her retrospective at the National Gallery of Singapore in the company of these two sons, Alex and Johnny, and I have to say there may be no more beautiful way to understand art than listening to brilliant creative minds speaking about another creative mind of which they have intimate knowledge. The retrospective, titled “The Space Between,” was the most comprehensive survey of Kim Lim’s work to date, and faithfully tracked the chronology of her sculpture and printmaking across four distinct chapters from her early wood constructions through her experiments in industrial minimalism to her return to wood and paper and negative space and then to her later poetic work in stone.

Born in Singapore in 1936, she moved to London in 1954 and became one of a small number of women active in the postwar British art world. One of the others, albeit a generation older, was Barbara Hepworth, who as a single mother of three left us one of the best lines about the parallel work of raising children and making art:

I think this idea of a working holiday was established in my mind very early indeed. It made a firm foundation for my working life – and it formed my idea that a woman artist is not deprived by cooking and having children, nor by nursing children with measles (even in triplicate) – one is in fact nourished by this rich life, provided one always does some work each day; even a single half hour, so that the images grow in one's mind.

You see all of these photographs of Kim Lim with her work in the 1960s looking extremely stylish next to her sculptures, the life and the work all of a piece together, completely of their moment and also completely of our moment. It’s easy to imagine how the work found the audience that it has and even easier to imagine everything it had to go through to get here. In one anecdote related by the exhibition timeline, we learned that Lim was the only woman and the only non-white person included in the first Hayward Annual; she was invited to the all-female jury of the second the following year. A figure balanced on a precipice.

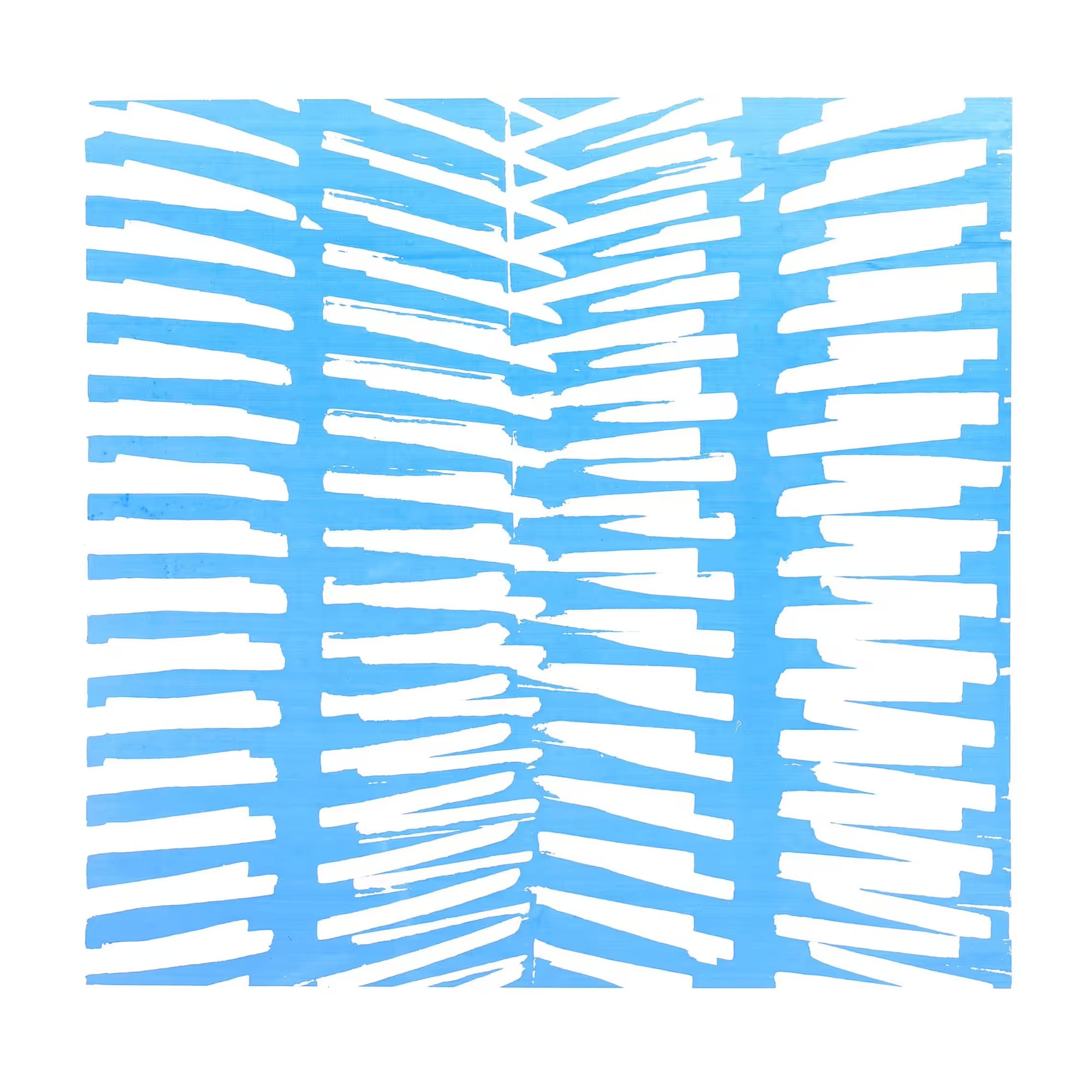

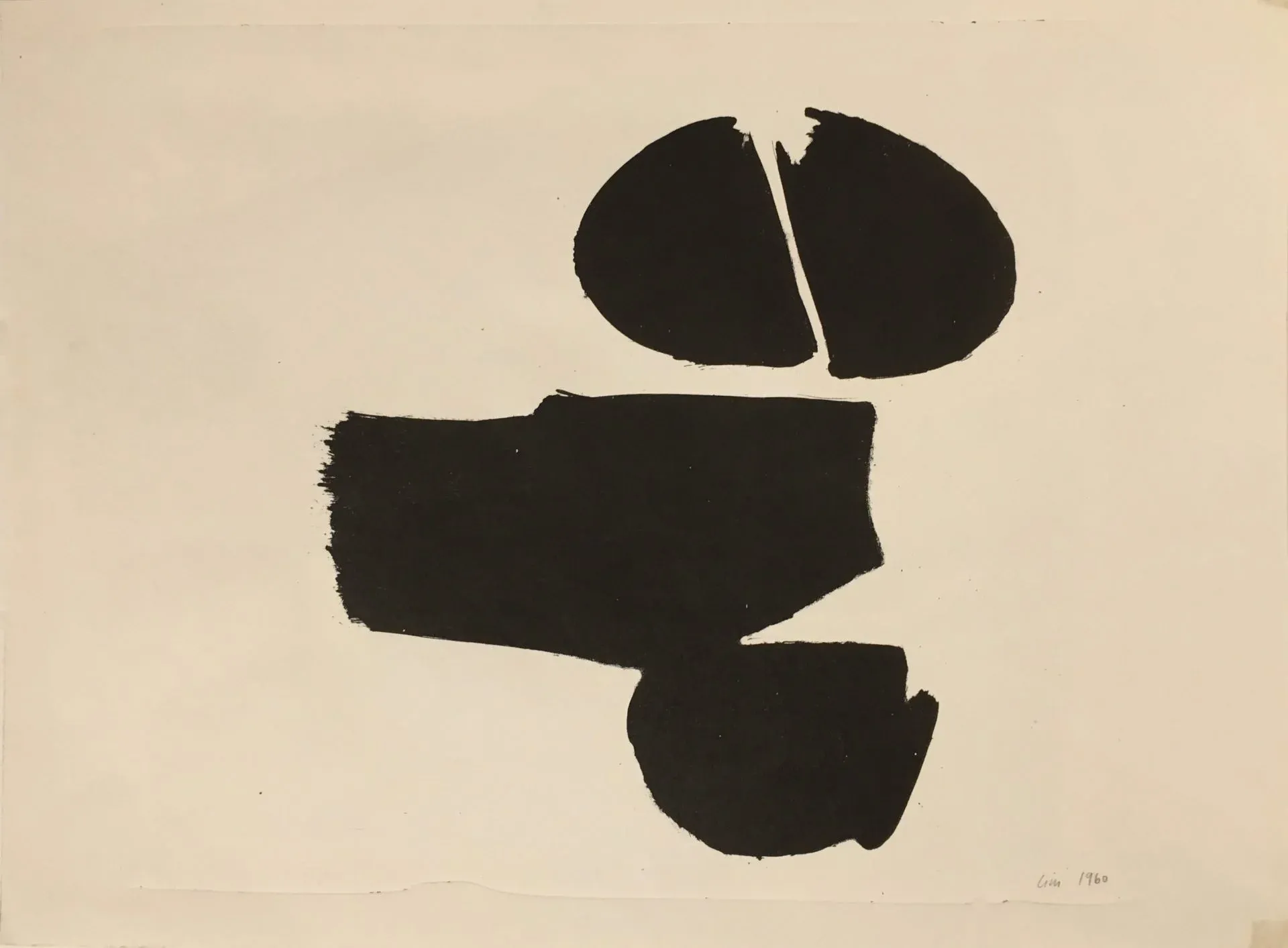

Clockwise from top left: Ronin, 1963; Intervals (Blue), 1972; Sphinx, 1959; Sphinx, 1960. All courtesy of the estate.

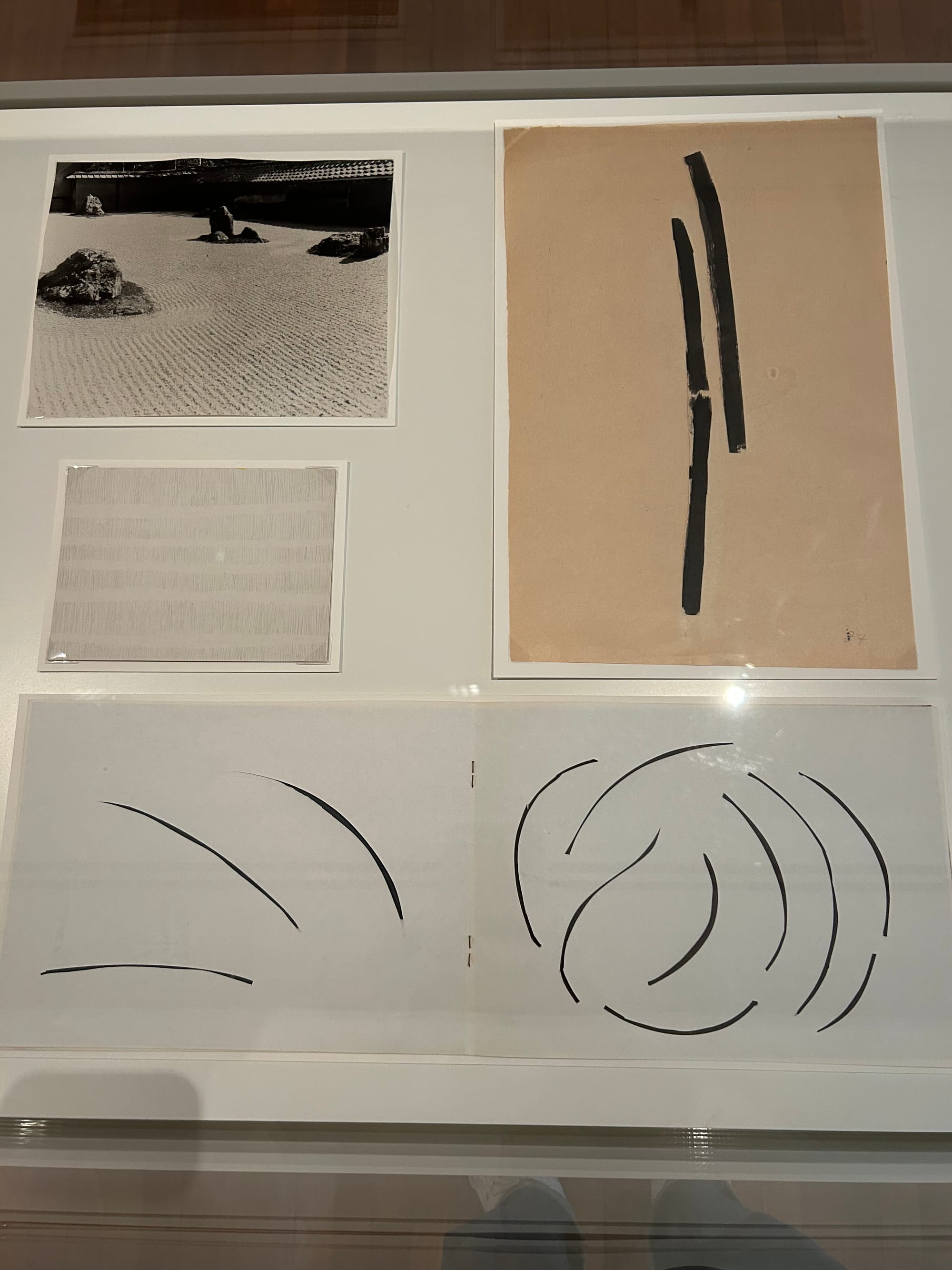

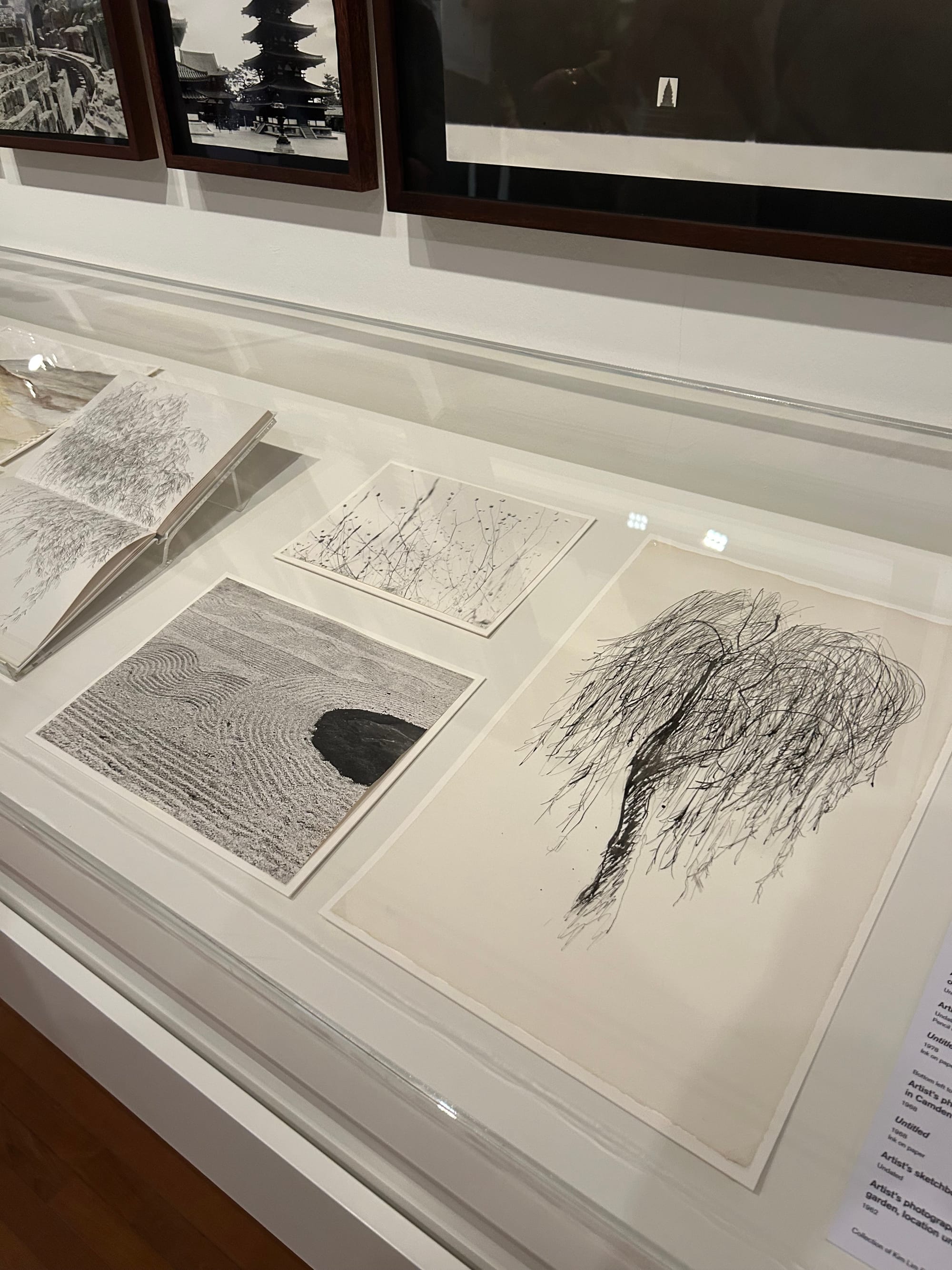

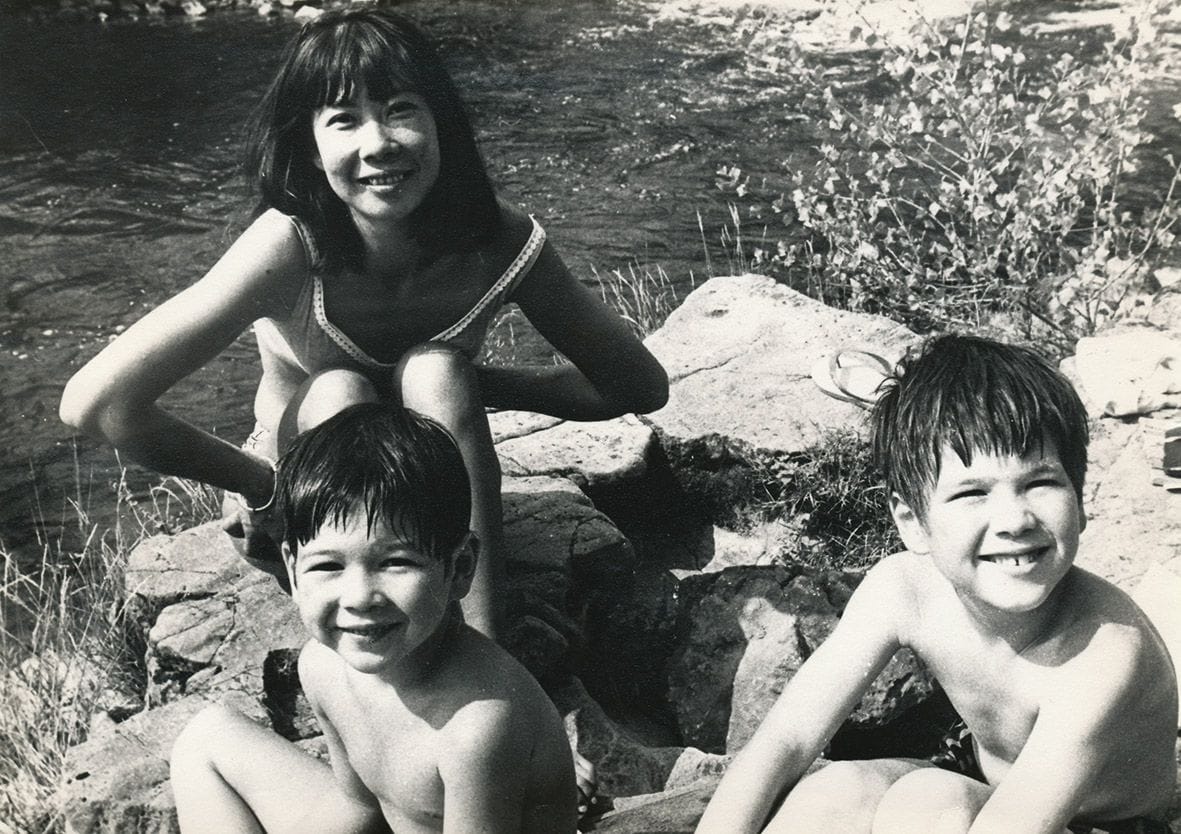

True to the title of the exhibition, some of the most touching moments on our tour of the show came in the spaces in between. The estate contributed a number of maquettes and archival material from the studio, materials that gained a particular resonance through Alex and Johnny’s familiarity. A wall of photographs became one of my favorites. At first glance, they looked like tourist snapshots. Upon closer examination, they revealed themselves as a highly curated collection of formal aspects of archaeological sites and monumental structures, many of which appear as references in Kim Lim’s work—from Stonehenge to Giza to Angkor Wat to Kyoto to the Cyclades. Then, with the added layer of personal narrative, they became a family photo album, opportunities for thinking about and sharing the aesthetic experience within the complex universe of the emotional life of a young family.

Alex and Johnny explained that these were study trips and working holidays, really, something that their parents started before they were born, seeking out direct access to art historical references that could be fruitful for their separate practices. Study trips but also honeymoons; study trips and then also family vacations. Growing up in this environment—and with a working stone carving facility for a backyard—it is no surprise that Alex and Johnny should have engaged with the creative life from a young age. To quote Alex:

There was an incredible respect and love between them [Kim Lim and William Turnbull]. You see in these amazing photos of them when they were young—both striking individuals. There was clearly a physical attraction but also a profound intellectual and artistic connection. They were drawn to each other not just as people but as artists, deeply inspired by each other’s work. Bill always said she was the best artist he knew, and I think he found as much inspiration in her work as she did in his. Though there are intersections in their art, their work remains distinct. … It’s fascinating that my parents came from such different backgrounds—Bill from a shipyard in Dundee and Kim from a well-off family in Singapore. Despite growing up in environments without art, they were somehow put onto this planet to do precisely what they did.

For all of these reasons I have always known that Kim Lim would play an important role in Nostos, but it was only when we arrived at the last chapter of the Singapore retrospective, the rooms about her later work in soft stone, that I started to understand how she would fit into this first essay. Titled “The Weight of Line,” this part of the exhibition draws explicit parallels between her mark-making practices at the foundation of her work with prints and the approach to form that we see in her best-known stone work made after 1979. (I say best-known, but in point of fact the resurgence of museum interest in her work has largely manifested itself in the other lesser-known bodies of work, particularly the wooden constructions, so perhaps this balance has already shifted.) Again the work came to life through Alex and Johnny, who described how their mother would go through cast-off blocks of stone from British quarries looking for a form she could work with, bringing them home to continue muscling them around in the garden. They pointed to a few specific lines that they found particularly weighty, instances of negative space inserted into reality. For me these lines and the phrase, “the weight of line,” called to mind something I have said about my dog’s collar: “the weight of belonging.” It’s a distinctly heavy chain, but she enjoys wearing it—whenever she hears someone pick it up off the counter she trots over and wags her tail and waits for it to be put back around her neck. My theory is that she bears its weight as a reminder of the affection and the mutual responsibility that comes with making a home together.

This weight of line brings us full circle to Alice Neel and Suzanne Valadon, to the distinct mark they share, the heavy dark outlines of their figures, one of the defining visual features of this practice of portraiture—a line that creates a relationship between the viewer and the viewed. In the case of Kim Lim I believe the weighted line holds together her practice across media, from the deep cuts in her stone sculpture to the physical weight of the pressed object that composes her prints. Throughout Lim’s work there is a play of rhythm and repetition, positive and negative space, a work of rocking back and forth to loosen and tighten, as if each time a form is repeated it settles further into a groove and deepens further its line. Art is a practice of discovering gravitas through experimentation.

Both of Kim Lim’s sons are highly creative people who have forged their own idiosyncratic practices and paths through art, music, film, and fashion across Europe and Asia. Alex Turnbull most recently completed the documentary Kim Lim: The Space Between, featuring a soundtrack by his brother Johnny Turnbull. Through this triangulation, they open up for all of us the rich matrix of ideas, forms, and love that they have spent their lives building.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Shorts is a regular column with links and commentary on family culture.

Matt Copson (KW Berlin)

Matt Copson, the artist whose laser animations are instantly recognizable, has his first major exhibition up in Berlin at KW with “Coming of Age. Age of Coming. Of Coming Age.” The main work is a trilogy following a baby that grows into / attempts to swallow the world, an everyman character born out of the fundamental contradiction in which we exist today: everything is horrible, and there’s nothing you can do about it.

And also, it’s an opera. The baby is an artist, a politician—all of us. Last weekend Copson and the writer Dean Kissick invited three children to join them on stage for a panel conversation on “Art and Meaning in the Contemporary Age.” It sadly doesn’t seem to have been filmed but perhaps we can cajole Dean and Matt into sharing some of the highlights with us.

Kasia Fudakowski (ChertLüdde)

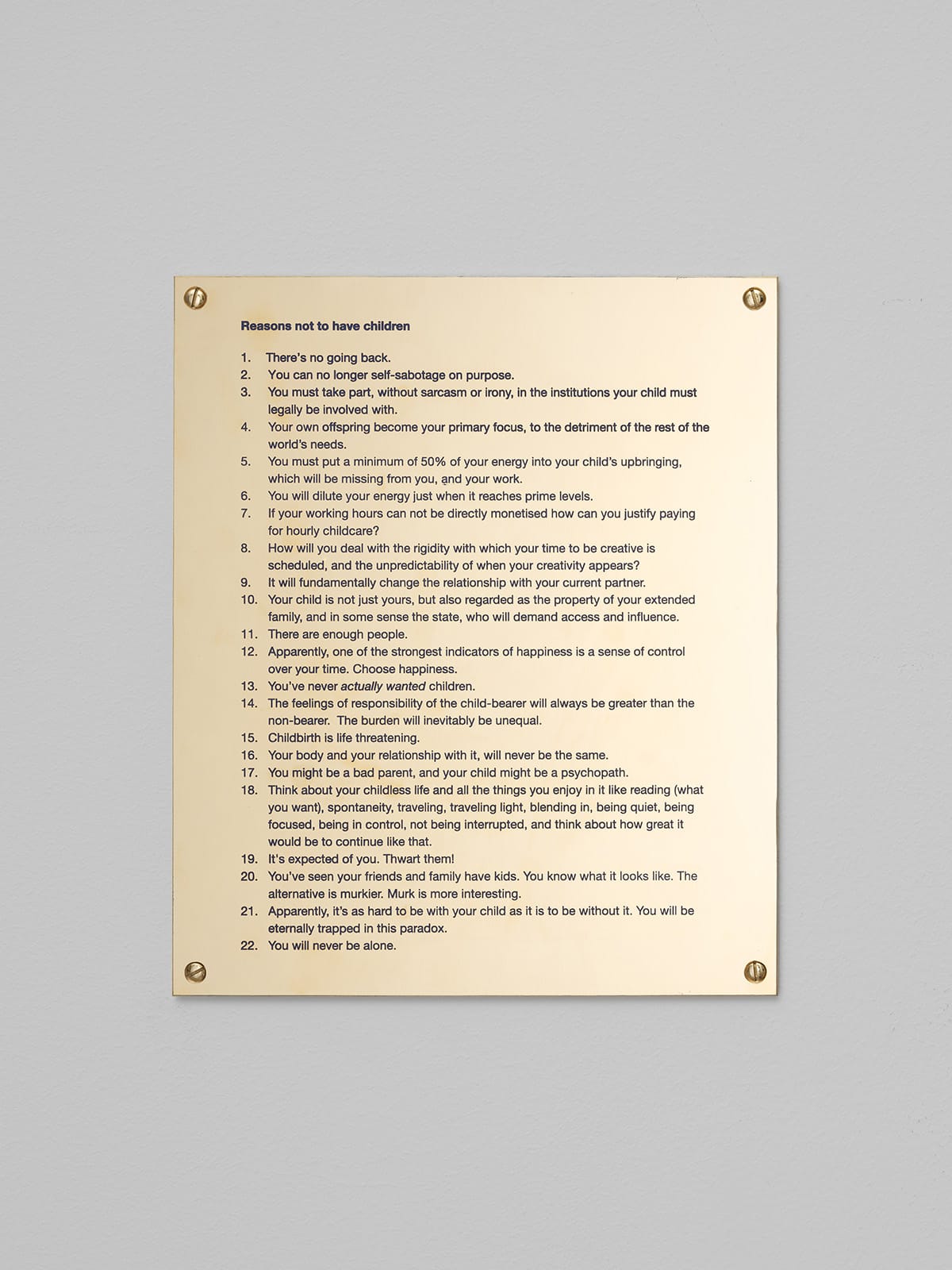

This work popped up on my feeds last week and I’m not sure exactly why, but since we’re on the topic of art and children in Berlin exhibitions I thought I’d share it here. I like how the pro and the con are presented side-by-side with no resolution, making permanent the state of the question, the debate, rather than the decision or the outcome.

Kasia Fudakowski, Reasons to Reproduce, Reasons Not to Reproduce, 2023

This was initially part of a solo exhibition by Fudakowski a couple years ago that was thinking about energy in the context of art, and she made some really interesting comments about how the question of reproduction becomes an energy sink at a certain age, to say nothing of reproduction itself. “You will dilute your energy just when it reaches prime levels.”

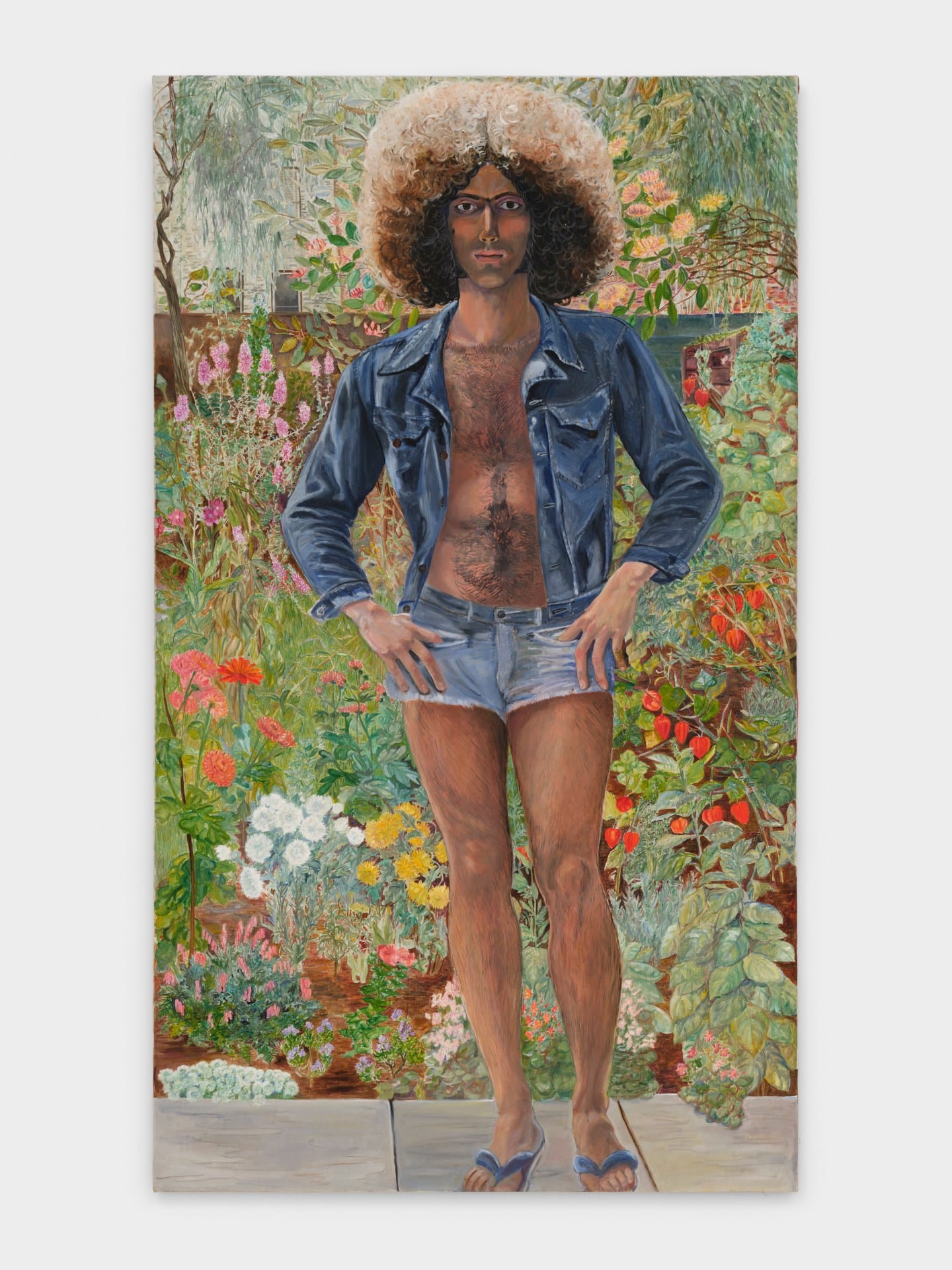

Sylvia Sleigh (Lévy Gorvy Dayan)

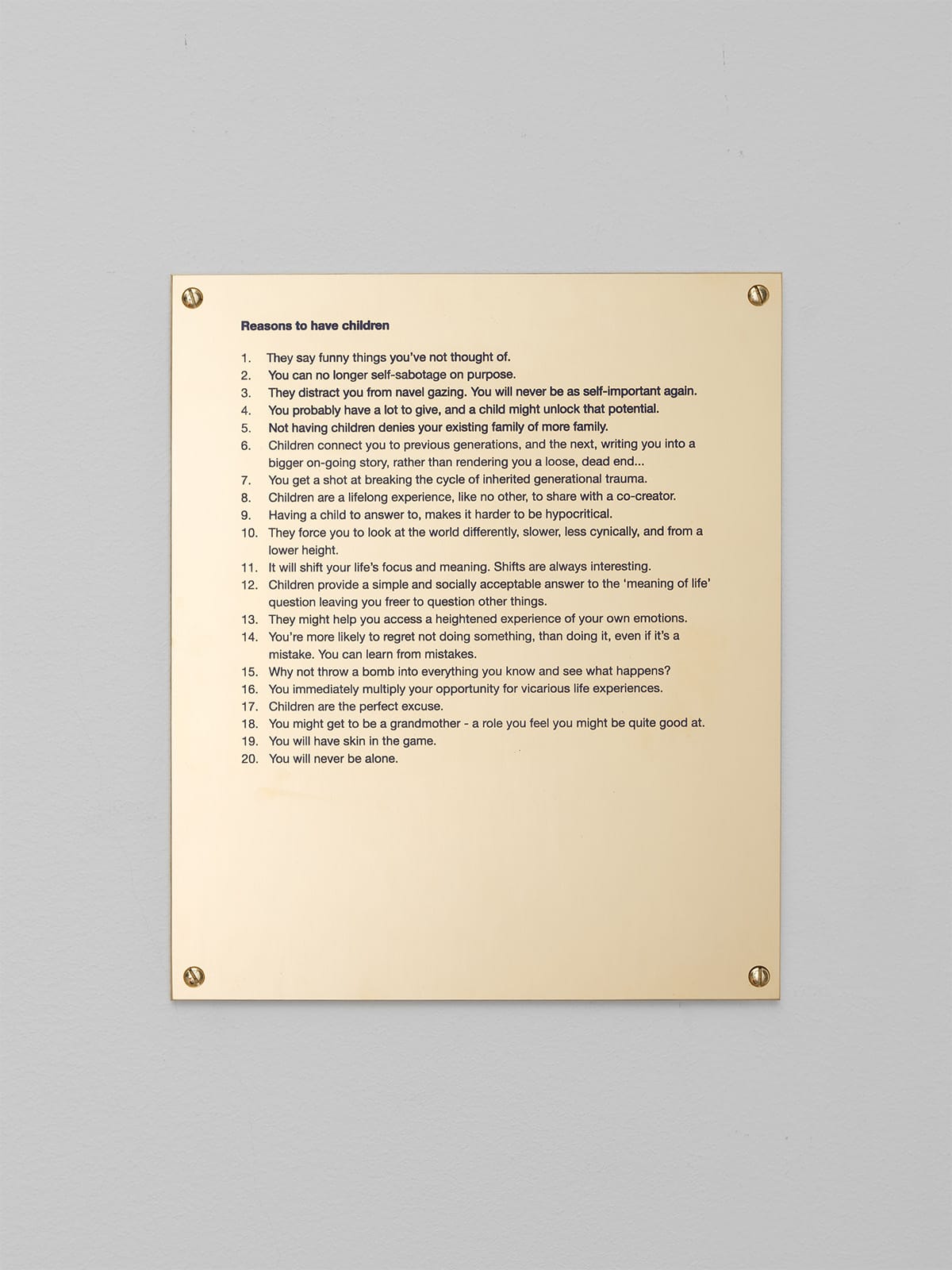

Rather unexpectedly the artist of the spring has been the late Sylvia Sleigh, whose solo exhibition with Ortuzar Projects ended in early April and then has been quickly reaffirmed by the tightly curated Lévy Gorvy Dayan group exhibition “The Human Situation,” which puts her alongside Alice Neel and Marcia Marcus. As with Neel, one of the most engaging aspects of Sleigh is the network of relations that is embedded into the portraiture.

If Neel’s talent was for leveling and humanizing, sympathetically stripping everyone down to a psychological essence, Sleigh’s was more like a drag show, swapping familiar figures into new and surprising roles. She’s been getting a lot of attention, for instance, for the way she strips down her male colleagues and lovers, turning art critics into odalisques, turning he who gazes into something to be gazed upon. In many pictures the textures of body hair and tanlines sit against foliage and patterned textiles, a delicate riot of sensation and experience.

And sometimes it’s a literal drag show: this is her husband Lawrence Alloway in a wedding gown, to my eye the very face of Orlando. There’s also a great episode of the Great Women Artists to listen to.

Coco Chanel’s La Pausa (New York Times)

Coco Chanel’s residence in the south of France has rejoined the house of Chanel after a half-century detour through Texas. Initially designed by Robert Streitz with reference to the Abbaye d'Aubazine where Chanel spent some of her childhood, the house has now been restored by Peter Marino to what is described as its 1936 state. From what we can see in the photographs released so far it is minimal and modern but not radically or dramatically so, of a piece with her mirrored Paris showroom, and seems like it would have made for a naturally informal and lived-in mode of entertaining.

Her many guests included Dalí, who lived and worked there in an unofficial artist-in-residence capacity. It will be exciting to see if Chanel’s art and culture programs will reinvigorate it in an interesting way—it says there will be a literary program in the fall and perhaps more to come.

Christopher Adams

Finally, as we are coming out of Taipei Dangdai Art & Ideas this week I want to share a couple projects by friends locally in Taipei. The first is “Island of Another Scene,” a stunning small-scale solo exhibition by Christopher Adams, which I somehow knew nothing about until it opened. I was blown away by the work and by its framing: Christopher presents some dozen portraits of artists, sometimes their faces, sometimes their work, sometimes a combination of the artist in the work.

Left to right, portraits of Luo Jr-Shin, Michael Lin, and Item Idem, with fragments of Fameme, Su Hui-Yu, and Su Misu

In the introduction to the project he talks about how the idea of relational aesthetics changed our understanding of what art is, and how the relationships that constitute art and its audience become a part of how we see the art. You could call it a practice of relational portraiture.

Penghu Perennial (PILL)

The day after Taipei Dangdai closed I flew to Penghu, an outlying island off the coast, for the inaugural edition of the Penghu Perennial hosted by the Penghu Institute of Labor & Leisure, a new art space founded by the Paris-based multihyphenate Item Idem. We gathered for the premiere of the new film Joss Joss by Cheng Ran and Item Idem, and I moderated a talk between these two brilliant artists while food designer Slow Chen conceptualized a hospitality experience using foraged local ingredients.

I think this can become an exciting place to gather and look forward to future iterations of the Perennial—but it will also be a great spot for artists and particularly artist families to rest, recover, and make new things.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Bookshelf is a regular column that reads books for, by, and about artist parents.

I recently read The Long Form by Kate Briggs, who is also a translator of Barthes and dragged a whole bunch of Barthes into this important novel. The title sets of up the terms of engagement: “the long form” is a term that Barthes uses to refer to the novel, and Briggs plays with the question of how the masculine, continuous, monumental conception of the novel (the Great American Novel and its ilk) intersects with other experiences of time, particularly the fragmented days of early motherhood. Over the course of a day, or a couple days intertwined—who can really tell in that haze—the narrator tends to a young baby, walking, bathing, nursing, napping, holding, reminiscing, and occasionally reading a freshly delivered secondhand copy of Tom Jones. This is the situation:

Caring for a baby was an activity, productive of its own relationality, and therefore open to anyone, to everyone. Its meaning came from the day-by-day walking and carrying through of an ancient set of gestures that were new to her, while also keeping on with her own self-care activities - feeding herself, washing herself - and finding original ways of doing them too (now accompanied, often while holding someone else). Undertaking these tasks, thinking about them: also, by necessity, doing the thinking that arose from the doing of them: testing and wondering, querying and revising, inventing and projecting. And it was true that they sometimes gave rise to unexpected, open-ended, unusual sorts of thoughts. Her days with Rose were making her look at herself, and the world, from other angles. They were making her do things (and think things) she had never considered doing (or had thought of) before. They were bringing her up against old questions, big questions, strange combinations of questions, hyphenating them and bracketing them and reaccenting them. They forced open the imagination in ways that might one day reveal themselves to have been transformative. For now, though, she just felt stupid. Or was it disappointed.

The narrator is much better versed in the history of the early modern English novel than I am, and of course also in the ins and outs of being a mother. But the fragmentation of time is instantly recognizable. It pulls me back to my first year with a baby in the apartment, to the frantic blocks of work wedged in during naps and quiet moments, to the single-minded bouts of activity aimed at attending to a newly awoken or newly upset or newly hungry baby, and to the sheets of pure presence that fell in between all of that, the skin and the smells and the smiles. It’s enough to call up a sentimental mood.

But why not ‘sentimental’ also in the sense that poet Friedrich Schiller ascribed to it? As one of two distinct attitudes towards writing and the world (towards writing the world). On the one hand: ‘naivety.’ The direct reporting of experience. Telling it. On the other: ‘sentimentality,’ a mode which draws on and makes explicit the poet's relationship to the materials, to the situation, to the experiencing of experience: ‘sentimental’ on his terms meaning situated and self-aware.

That resonates nicely with the way that I’ve been thinking about biographical criticism and autofiction, gently pulling together a framework to evaluate the degree of self-awareness that these modes of writing or making art bring to each other. Briggs is extraordinary for the way her criticism is built directly into her fiction. The Long Form plays with the way that language is broken up, both within the narrative of the text and in the housing of the narrative. I love this bit in particular, as a demonstration of this point but also because it’s a beautiful realization of what it means to be alive, the weight of responsibility for the self and sometimes others that we wake up to every day:

… no one had taken her aside and warned her. There would be no sudden extension to the space of her character, no instant expansion of patience and tolerance — no. To be clear: there would be no immediate, radical inner change. Instead, there would just be —

THE DOING OF IT

It was her discovery.

Listen - she wanted to tell someone: this is what it involves.

Doing it.

That line that’s written all in capital letters in the middle? That’s a section or sub-chapter heading. The passage preceding it ends a left-hand page, cutting off the sentence right in the middle with the dash, and then the title of the next chapter resumes the sentence. After which the body of the chapter continues on, so that the chapter heading isn’t an interruption at all but a bit of concrete poetry that carries on its own weight within the story. The book, which achieves the length of its form through an accumulation of fragments and is all the richer for it, becomes a vessel for the holding of all of this poetry. And holding is what the whole things is all about—it’s what occupies the narrators day:

Their day was the story of their holding arrangements: an ongoing narrative of finding (sometimes planning, sometimes inventing, making up) and holding to (for as long as they lasted: believing in), then collapsing little scenes.

Allowing them, stretching them out.

The meaning of holding: to maintain, to sustain, to support. To stop and stay. To keep to, and persist in. A situation involving an intentionality as well as the promise of a certain duration.

This practice of holding is something that is familiar to anyone who works as a caregiver to children, anyone who works as a homemaker, but also to anyone who works with creative people and helps to guide the creative process. (As an aside, my favorite thing about the physical format of these Fitzcarraldo Editions novels is how the blue slowly wears down to white, revealing a how the book has been held over time—its holding pattern.

Tolerating the collapses and the breaks, committed to re-establishing the sorts of environments that hold steady enough and prove flexible enough to accommodate someone else's discoveries: the provision of a mutually invested setting to imagine out from.

This is what I love about what I do, in my professional work as someone who tries to make interesting contexts for artists to bring their work to the world, and equally also in my personal work as a father to someone who is struggling every day to bring herself out into the world. Love is holding space, building an architecture for that space to appear. I’m fond of saying that love is a practice:

It’s alright if love feels like a rhythm of reaching and falling short. Then an unexpected receiving—a sometimes wholly unsought interaction, having nothing whatsoever to do with ambition. A dispossession. Not an achieved steadiness.

It’s alright if the feelings you feel are so mixing and mixed. If there can be patches of the day when you feel panic, then nothing - not a thing for anybody, not even for yourself.

The key is to keep going.

It’s alright if the whole project can sometimes feel like an unsupported invention, an unprecedented co-production.

It’s alright. Say it's alright.

It’s okay. It is (going to have to be) alright.

In her reading of Tom Jones (and not just Henry Fielding, also E.M. Forster and Bakhtin, among others) alongside and throughout her rituals of love and holding, the narrator establishes that the novel always contains disruption and discontinuity, and that to pretend otherwise is to be blind to their rhythms. In my favorite sub-plot, the driver delivering the novel rings the doorbell and awakens the baby, which seems thoughtless to the narrator and of course completely innocent to the driver. But we get to follow the driver for a bit on his route through the neighborhood, and we come to understand that he is waiting for a text from a paramour. With the Barthes connection in mind, I immediately jumped to A Lover’s Discourse and the temporality of waiting, the expectant yearning that Barthes unravels so beautifully: the lover is the one who waits. The lover carries the weight of that empty space. As the driver continues through the streets and alleys and the narrator attempts to hold her baby we become privy to two kinds of time running in parallel. Intertwined processes of reading and writing bring the text into life.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Essays is an occasional column that teases out in greater depth how family life appears in culture.

Towards the end of the Suzanne Valadon exhibition, in the valedictory bit where the museum reminds you which key points you’re meant to take home with you, some objective claims are made about the daring nature of her work. She was, we are told, the first woman to paint a full-frontal male nude (Adam and Eve, 1909). She is Eve, and her lover André Utter is Adam, some 20 years her junior, guiding her hand—or perhaps arresting it?—towards the forbidden fruit. Today we see Adam/André with his genitals covered with a fig leaf belt, a later addition, and we are supplied with a photograph of the original version of the work, a double image of play and propriety. Valadon was also the first woman to paint a large-scale full-frontal nude self-portrait. And, whether or not they were the first to anything, there is something striking and raw and courageous in the way she depicts her body as she ages, as we saw in Part IV of this essay. In the 1931 Autoportrait aux sens nus we looked at last time she would have been 65.

Seeing Valadon at the Pompidou, tracing the thickness of her line and the wrinkles on her faces, brought me back to another visit to the same museum in the fall of 2022, when an Alice Neel retrospective occupied a somewhat smaller, denser space downstairs. Full of stunning pictures, that was probably the exhibition that made Neel contemporary for me, and again was one of the important links in helping me understand portraiture. It had a certain angle: it was particularly interested in Neel’s activism, and in helping the viewer understand that her sitters were not selected at random, not selected on aesthetic grounds. Neel chose who to paint out of a sense of radical social solidarity, an insistence on reflecting back a shape of society as it interested her. It was very much Neel for the high water mark of social practice. Because of how she grasps at these various cross sections of society, Neel’s work now constitutes an archive that lends itself well to such readings at a certain angle. More recently, Hilton Als curated “At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World,” another gathering of characters from her universe that has a lot to teach us about life in the queer family.

When Alice Neel painted her famous Self-Portrait (1980) she was 80, some 15 years older than Valadon in the picture we looked at previously. What is surprising about the Neel is not that she would depict herself in the nude at that age, but rather that she painted herself so rarely, and that it hadn’t happened sooner. The title “self-portrait” appears in her work only one other time, with the Self-Portrait Skull (1958), an ink drawing of a gaunt and leaky skeletal face that forms a stark contrast with the ruddy and very much alive version of herself that Neel actually encountered towards the end of her life.

And while she might not have called them self-portraits, there are a few other paintings that Neel made of herself. We see one in Mother and Child (Alice) (1930) [on the estate's website this one is titled Alice and Her Child]. Even exhibitions of Neel’s early work rarely venture this early; the style is nigh unrecognizable, though still pretty cool looking. At the risk of sliding into the kind of biographical interpretation that we have by now agreed can be simplistic, it is important to understand that she painted herself in a cemetery here because her first-born daughter died at the end of 1927 at less than a year old. Her second daughter, born in 1928, was taken by her then-husband to be raised by his family in Cuba before she was 18 months old. There is another painting, another Mother and Child, this one from 1927, in which the baby’s eyes are open, and there are no tombstones in the background. In her brilliant essay “Futility of Effort: Alice Neel and Motherhood, 1940-46,” Lauren O’Neill-Butler speculates that an even odder painting, Degenerate Madonna (1930), is a “psychological portrait” of this trying time. Her essay is titled after a third 1930 painting of a baby asphyxiated by the bars of its crib.

Until I looked at these paintings, I hadn’t thought too much about Neel’s daughters, rest their souls. I think often about her sons, whose life trajectory seems like a nightmare for the creative parent: one became a “self-described ‘right wing’ investment adviser,” and neither of them had much affection for the bohemian milieu of their childhood. Her grandchildren, fortunately, count among them an abstract painter and a filmmaker, the latter of whom shot a touching documentary that weighs up the rewards and risks of an artist’s life. To be fair, her sons share a respect for her accomplishments, if not a full forgiveness for the price they paid. The arc of history is long.

Neel’s sons come to mind often in large part because she is the first artist analyzed in one of my favorite books, The Baby on the Fire Escape: Creativity, Motherhood, and the Mind-Baby Problem. Already in the title Julie Phillips refers to an anecdote from Alice Neel’s life: Isabetta, the daughter who was taken to live with Neel’s in-laws, was later told that Neel had left her on a fire escape while she was painting. As with This Dark Country, I have learned a lot from this group biography about the limits and possibilities of writing about the artist’s work and the artist’s life side by side (“her awareness of parental entanglements often gets into her portraits”). For the most part, Phillips writes about writers: Doris Lessing, Ursula K. Le Guin, Audre Lorder, Alice Walker, Angela Carter. Neel is an exception, and this is perhaps what makes her case particularly compelling. Across these figures we read about different approaches to love and romance, to the labor of child-rearing, to domestic responsibilities, to creative labor, to gender in general. There are no answers, no conclusions, no one right way to do things. In the end, there is only the way things happened. Ginny Neel, who married Alice Neel’s youngest son, says that Alice “became famous … so it was worth it. Just the slightest twist and she could have never been much heard of. And then what, it wouldn’t have been worth it?” Towards the end of her life, Alice herself answered. “What will they think of me afterwards? You know, I had to do this. I couldn’t have lived, otherwise.”

On that 2022 trip to Paris, when Alice Neel was showing on the mezzanine floor, I attended a cocktail back upstairs hosted by Chanel’s Yana Peel for the rededication of a terrace in memory of the recently passed architect of the building, Richard Rogers. During the ceremony Ruthie Rogers gave a moving speech in which she recalled a conversation they had in their Paris years, where they lived during the construction of the Pompidou. She remembered that they had stopped at a cafe late in the evening, she in her 20s and he in his early 40s, and they were watching an older couple on a night out at an adjacent table, and he projected forward a future idyll: to be elderly, in love, and fully alive—in Paris. Paris represented something for them, a way of living that would have consequences for our understanding of how a city should work. I often listen to Ruthie’s Table 4, a charming podcast in which the host talks over her famous guests indiscriminately and retells their stories as her own, as all good storytellers do. Recently she had on Bella Freud, and they reminisced over Lucien Freud’s midday drives from Soho to the River Cafe. I love these stories, generation to generation, splintered family to familiar splinter. Bella Freud has her own equally charming podcast called Fashion Neurosis.

What a thing to imagine the early 1930s, this moment of overlap that materializes across the floors of the Pompidou: an aging Suzanne Valadon facing the mirror topless in Montmartre, her grown son by then also an artist, while in Greenwich Village a bereft Alice Neel painted through the loss of her two first children, not yet settled into her neighborhood, her apartment, her practice—not yet settled into the language that would become her own. She had to find her way there. She couldn’t have lived, otherwise.