Essay: Real Paintings and Fictional Painters (Part V)

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Essays is an occasional column that teases out in greater depth how family life appears in culture.

Towards the end of the Suzanne Valadon exhibition, in the valedictory bit where the museum reminds you which key points you’re meant to take home with you, some objective claims are made about the daring nature of her work. She was, we are told, the first woman to paint a full-frontal male nude (Adam and Eve, 1909). She is Eve, and her lover André Utter is Adam, some 20 years her junior, guiding her hand—or perhaps arresting it?—towards the forbidden fruit. Today we see Adam/André with his genitals covered with a fig leaf belt, a later addition, and we are supplied with a photograph of the original version of the work, a double image of play and propriety. Valadon was also the first woman to paint a large-scale full-frontal nude self-portrait. And, whether or not they were the first to anything, there is something striking and raw and courageous in the way she depicts her body as she ages, as we saw in Part IV of this essay. In the 1931 Autoportrait aux sens nus we looked at last time she would have been 65.

Seeing Valadon at the Pompidou, tracing the thickness of her line and the wrinkles on her faces, brought me back to another visit to the same museum in the fall of 2022, when an Alice Neel retrospective occupied a somewhat smaller, denser space downstairs. Full of stunning pictures, that was probably the exhibition that made Neel contemporary for me, and again was one of the important links in helping me understand portraiture. It had a certain angle: it was particularly interested in Neel’s activism, and in helping the viewer understand that her sitters were not selected at random, not selected on aesthetic grounds. Neel chose who to paint out of a sense of radical social solidarity, an insistence on reflecting back a shape of society as it interested her. It was very much Neel for the high water mark of social practice. Because of how she grasps at these various cross sections of society, Neel’s work now constitutes an archive that lends itself well to such readings at a certain angle. More recently, Hilton Als curated “At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World,” another gathering of characters from her universe that has a lot to teach us about life in the queer family.

When Alice Neel painted her famous Self-Portrait (1980) she was 80, some 15 years older than Valadon in the picture we looked at previously. What is surprising about the Neel is not that she would depict herself in the nude at that age, but rather that she painted herself so rarely, and that it hadn’t happened sooner. The title “self-portrait” appears in her work only one other time, with the Self-Portrait Skull (1958), an ink drawing of a gaunt and leaky skeletal face that forms a stark contrast with the ruddy and very much alive version of herself that Neel actually encountered towards the end of her life.

And while she might not have called them self-portraits, there are a few other paintings that Neel made of herself. We see one in Mother and Child (Alice) (1930) [on the estate's website this one is titled Alice and Her Child]. Even exhibitions of Neel’s early work rarely venture this early; the style is nigh unrecognizable, though still pretty cool looking. At the risk of sliding into the kind of biographical interpretation that we have by now agreed can be simplistic, it is important to understand that she painted herself in a cemetery here because her first-born daughter died at the end of 1927 at less than a year old. Her second daughter, born in 1928, was taken by her then-husband to be raised by his family in Cuba before she was 18 months old. There is another painting, another Mother and Child, this one from 1927, in which the baby’s eyes are open, and there are no tombstones in the background. In her brilliant essay “Futility of Effort: Alice Neel and Motherhood, 1940-46,” Lauren O’Neill-Butler speculates that an even odder painting, Degenerate Madonna (1930), is a “psychological portrait” of this trying time. Her essay is titled after a third 1930 painting of a baby asphyxiated by the bars of its crib.

Until I looked at these paintings, I hadn’t thought too much about Neel’s daughters, rest their souls. I think often about her sons, whose life trajectory seems like a nightmare for the creative parent: one became a “self-described ‘right wing’ investment adviser,” and neither of them had much affection for the bohemian milieu of their childhood. Her grandchildren, fortunately, count among them an abstract painter and a filmmaker, the latter of whom shot a touching documentary that weighs up the rewards and risks of an artist’s life. To be fair, her sons share a respect for her accomplishments, if not a full forgiveness for the price they paid. The arc of history is long.

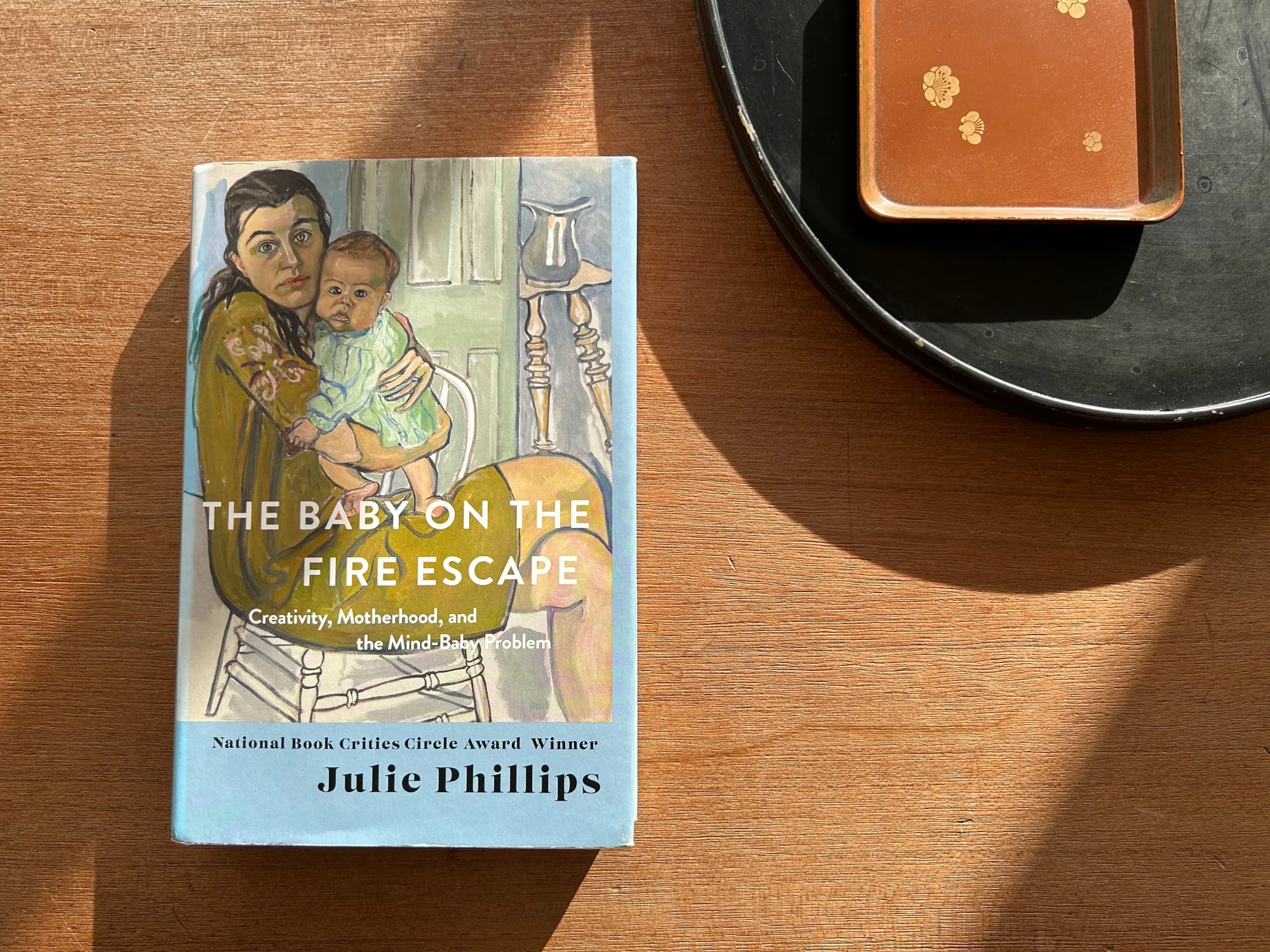

Neel’s sons come to mind often in large part because she is the first artist analyzed in one of my favorite books, The Baby on the Fire Escape: Creativity, Motherhood, and the Mind-Baby Problem. Already in the title Julie Phillips refers to an anecdote from Alice Neel’s life: Isabetta, the daughter who was taken to live with Neel’s in-laws, was later told that Neel had left her on a fire escape while she was painting. As with This Dark Country, I have learned a lot from this group biography about the limits and possibilities of writing about the artist’s work and the artist’s life side by side (“her awareness of parental entanglements often gets into her portraits”). For the most part, Phillips writes about writers: Doris Lessing, Ursula K. Le Guin, Audre Lorder, Alice Walker, Angela Carter. Neel is an exception, and this is perhaps what makes her case particularly compelling. Across these figures we read about different approaches to love and romance, to the labor of child-rearing, to domestic responsibilities, to creative labor, to gender in general. There are no answers, no conclusions, no one right way to do things. In the end, there is only the way things happened. Ginny Neel, who married Alice Neel’s youngest son, says that Alice “became famous … so it was worth it. Just the slightest twist and she could have never been much heard of. And then what, it wouldn’t have been worth it?” Towards the end of her life, Alice herself answered. “What will they think of me afterwards? You know, I had to do this. I couldn’t have lived, otherwise.”

On that 2022 trip to Paris, when Alice Neel was showing on the mezzanine floor, I attended a cocktail back upstairs hosted by Chanel’s Yana Peel for the rededication of a terrace in memory of the recently passed architect of the building, Richard Rogers. During the ceremony Ruthie Rogers gave a moving speech in which she recalled a conversation they had in their Paris years, where they lived during the construction of the Pompidou. She remembered that they had stopped at a cafe late in the evening, she in her 20s and he in his early 40s, and they were watching an older couple on a night out at an adjacent table, and he projected forward a future idyll: to be elderly, in love, and fully alive—in Paris. Paris represented something for them, a way of living that would have consequences for our understanding of how a city should work. I often listen to Ruthie’s Table 4, a charming podcast in which the host talks over her famous guests indiscriminately and retells their stories as her own, as all good storytellers do. Recently she had on Bella Freud, and they reminisced over Lucien Freud’s midday drives from Soho to the River Cafe. I love these stories, generation to generation, splintered family to familiar splinter. Bella Freud has her own equally charming podcast called Fashion Neurosis.

What a thing to imagine the early 1930s, this moment of overlap that materializes across the floors of the Pompidou: an aging Suzanne Valadon facing the mirror topless in Montmartre, her grown son by then also an artist, while in Greenwich Village a bereft Alice Neel painted through the loss of her two first children, not yet settled into her neighborhood, her apartment, her practice—not yet settled into the language that would become her own. She had to find her way there. She couldn’t have lived, otherwise.