Essay: Real Paintings and Fictional Painters (Part VI)

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Essays is an occasional column that teases out in greater depth how family life appears in culture.

It’s something that is repeated often about the occasionally codependent relationships artists have with their work: they couldn’t have lived otherwise. They couldn’t have lived, otherwise. I have no doubt that this is true, that artistic practice plays a constructive or even therapeutic role—that creativity and making and putting something out into the world is one of the things that makes life worth living. But it also seems to be trotted out a bit too often as an excuse for the bad behavior of artists, as if the artistic impulse were in control of their life decisions. This impulse, certainly, is a powerful thing. Over time my interest in what art can do has drifted into the camp of the pro-social, into forms of practice that are inherently social and relational. We want art to shatter our illusions, to break things, to fail spectacularly and in doing so show us the limits of what we are able to imagine, and there are ways for this revolutionary, violent impulse to be channeled into the practice. We have spent a lot of time with Alice Neel, whose two sons had an ambivalent relationship with their mother’s practice and bohemian lifestyle and took their lives in another direction. To conclude this series, I want to turn to the work of Kim Lim, a sculptor a generation or so younger than Neel whose radical work was intertwined with a life of love and cultivation, and whose two sons carry on her legacy both directly and indirectly, continuing to advocate for her profile by shepherding her estate while also developing their own pro-social creative practices. She said of the configuration of their relationship in 1966:

I virtually ceased to be an artist when the children were born and while I felt they needed my full attention. I don’t regret one moment of that time, but since one is now at school, and the other will soon be going, I have returned to art. Of course, it’s different being a woman—but it needn’t be a disadvantage. What one needs is tenacity to keep on working-to sculpture without denying domesticity.

This winter I had the immense pleasure of viewing her retrospective at the National Gallery of Singapore in the company of these two sons, Alex and Johnny, and I have to say there may be no more beautiful way to understand art than listening to brilliant creative minds speaking about another creative mind of which they have intimate knowledge. The retrospective, titled “The Space Between,” was the most comprehensive survey of Kim Lim’s work to date, and faithfully tracked the chronology of her sculpture and printmaking across four distinct chapters from her early wood constructions through her experiments in industrial minimalism to her return to wood and paper and negative space and then to her later poetic work in stone.

Born in Singapore in 1936, she moved to London in 1954 and became one of a small number of women active in the postwar British art world. One of the others, albeit a generation older, was Barbara Hepworth, who as a single mother of three left us one of the best lines about the parallel work of raising children and making art:

I think this idea of a working holiday was established in my mind very early indeed. It made a firm foundation for my working life – and it formed my idea that a woman artist is not deprived by cooking and having children, nor by nursing children with measles (even in triplicate) – one is in fact nourished by this rich life, provided one always does some work each day; even a single half hour, so that the images grow in one's mind.

You see all of these photographs of Kim Lim with her work in the 1960s looking extremely stylish next to her sculptures, the life and the work all of a piece together, completely of their moment and also completely of our moment. It’s easy to imagine how the work found the audience that it has and even easier to imagine everything it had to go through to get here. In one anecdote related by the exhibition timeline, we learned that Lim was the only woman and the only non-white person included in the first Hayward Annual; she was invited to the all-female jury of the second the following year. A figure balanced on a precipice.

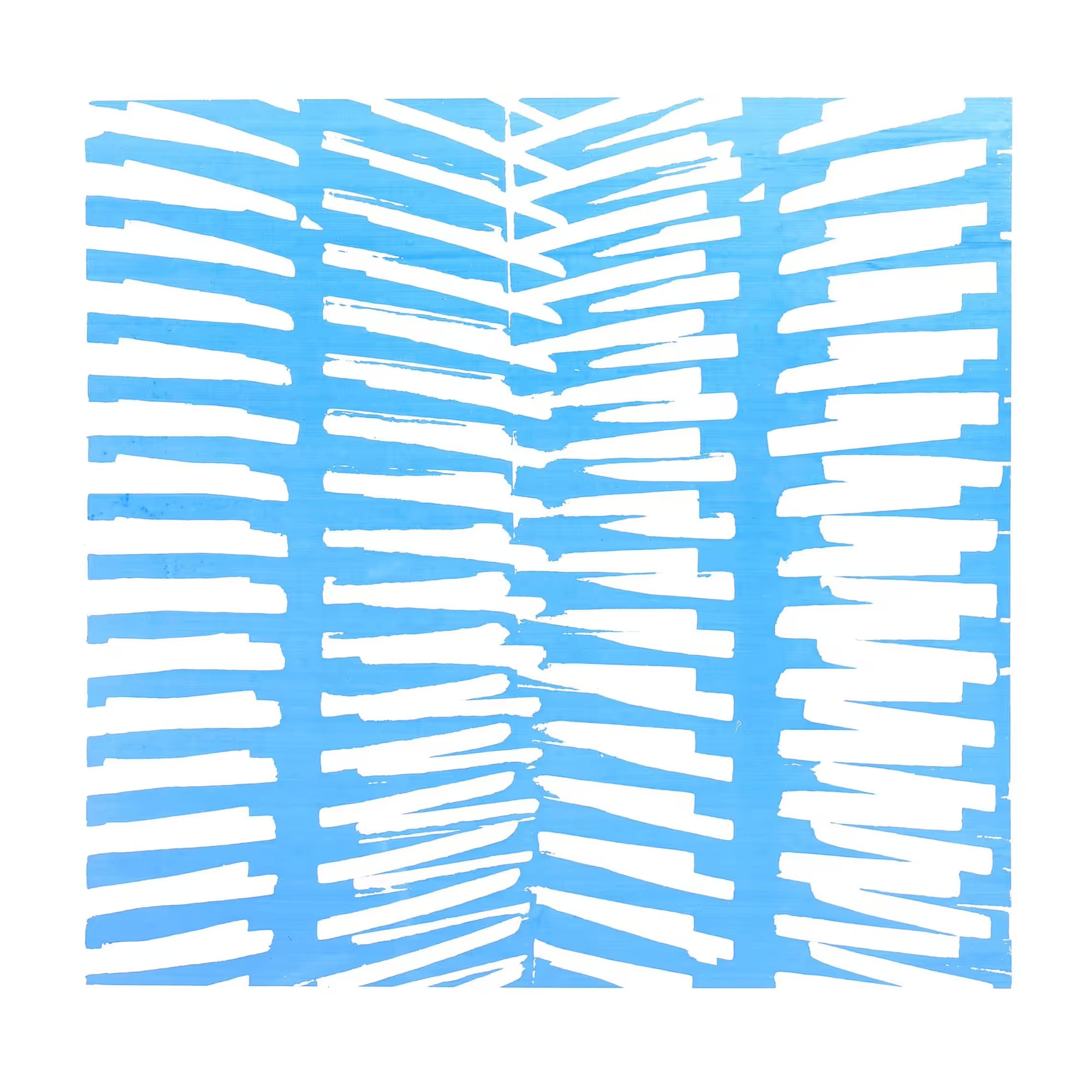

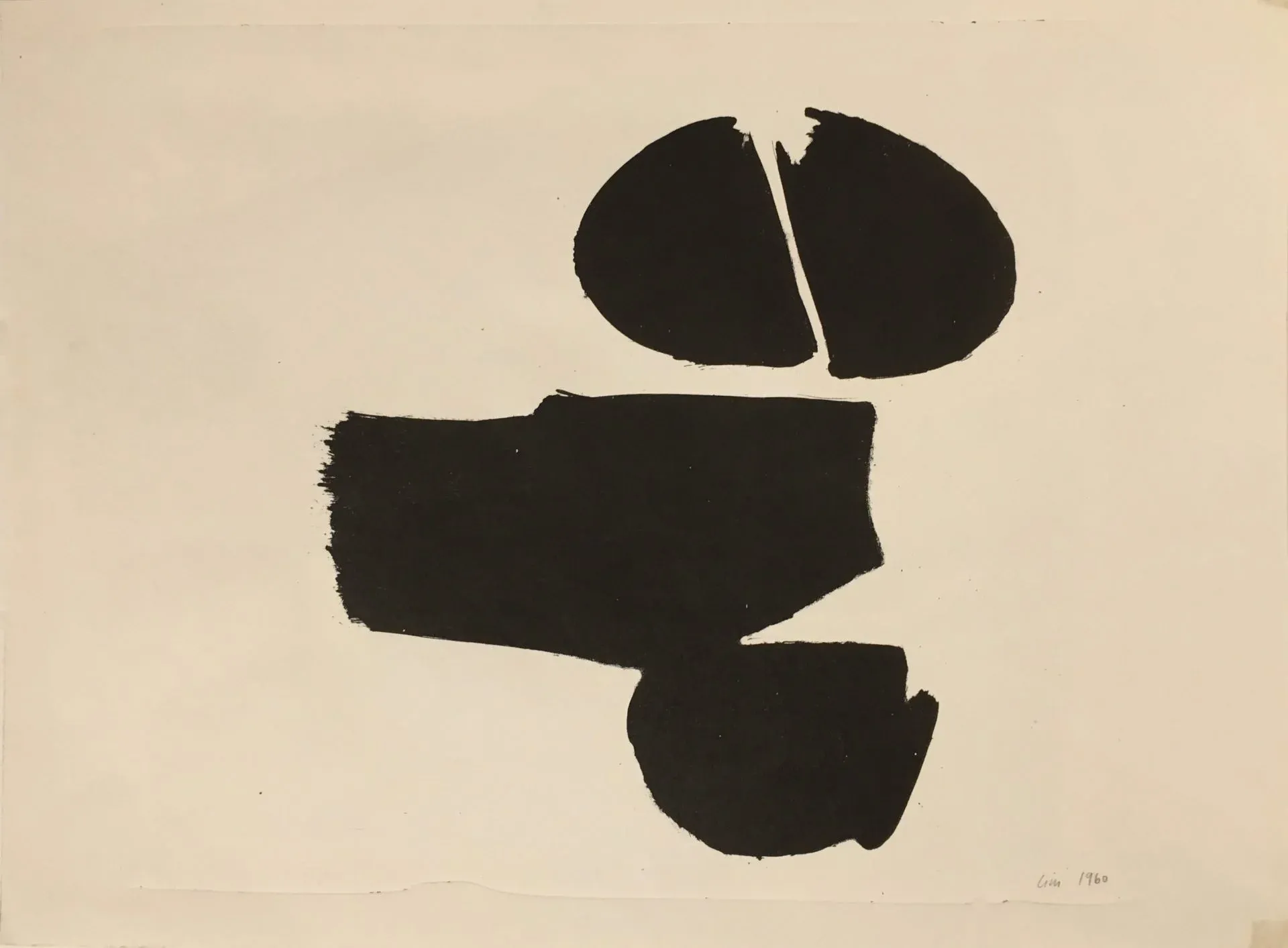

Clockwise from top left: Ronin, 1963; Intervals (Blue), 1972; Sphinx, 1959; Sphinx, 1960. All courtesy of the estate.

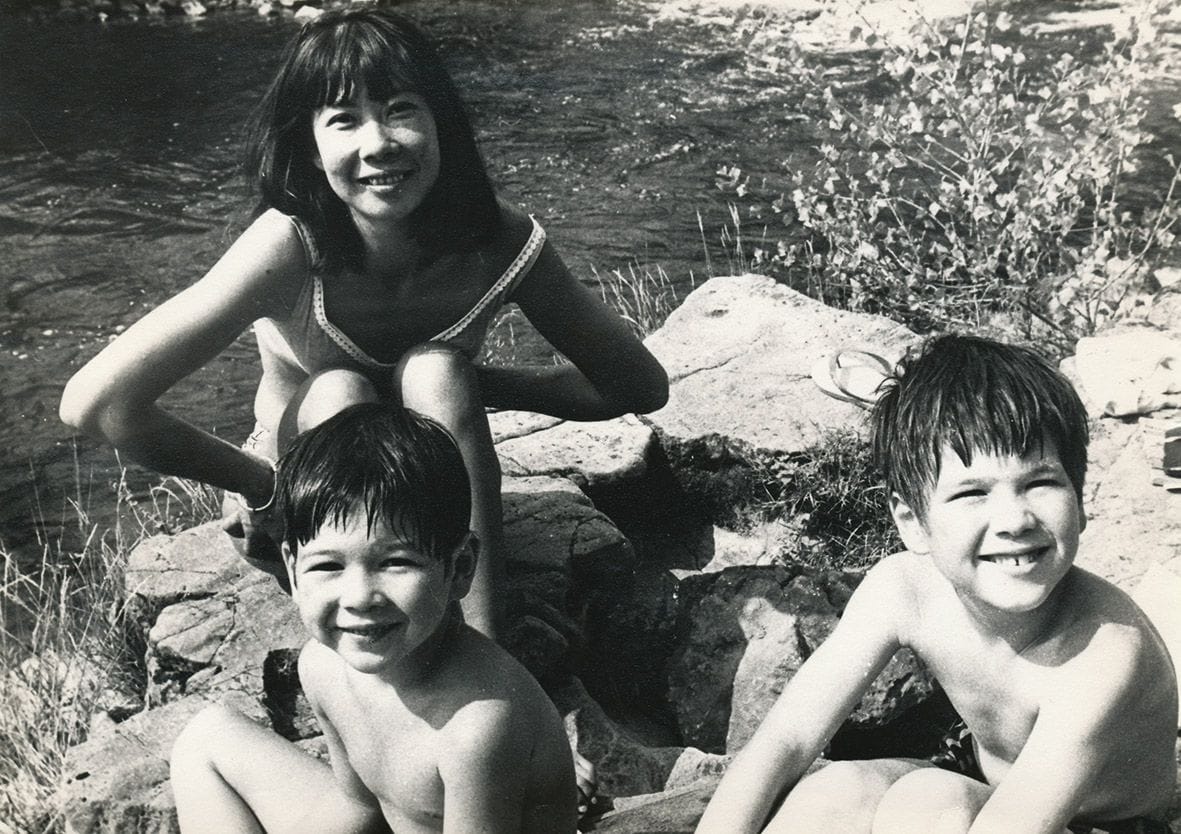

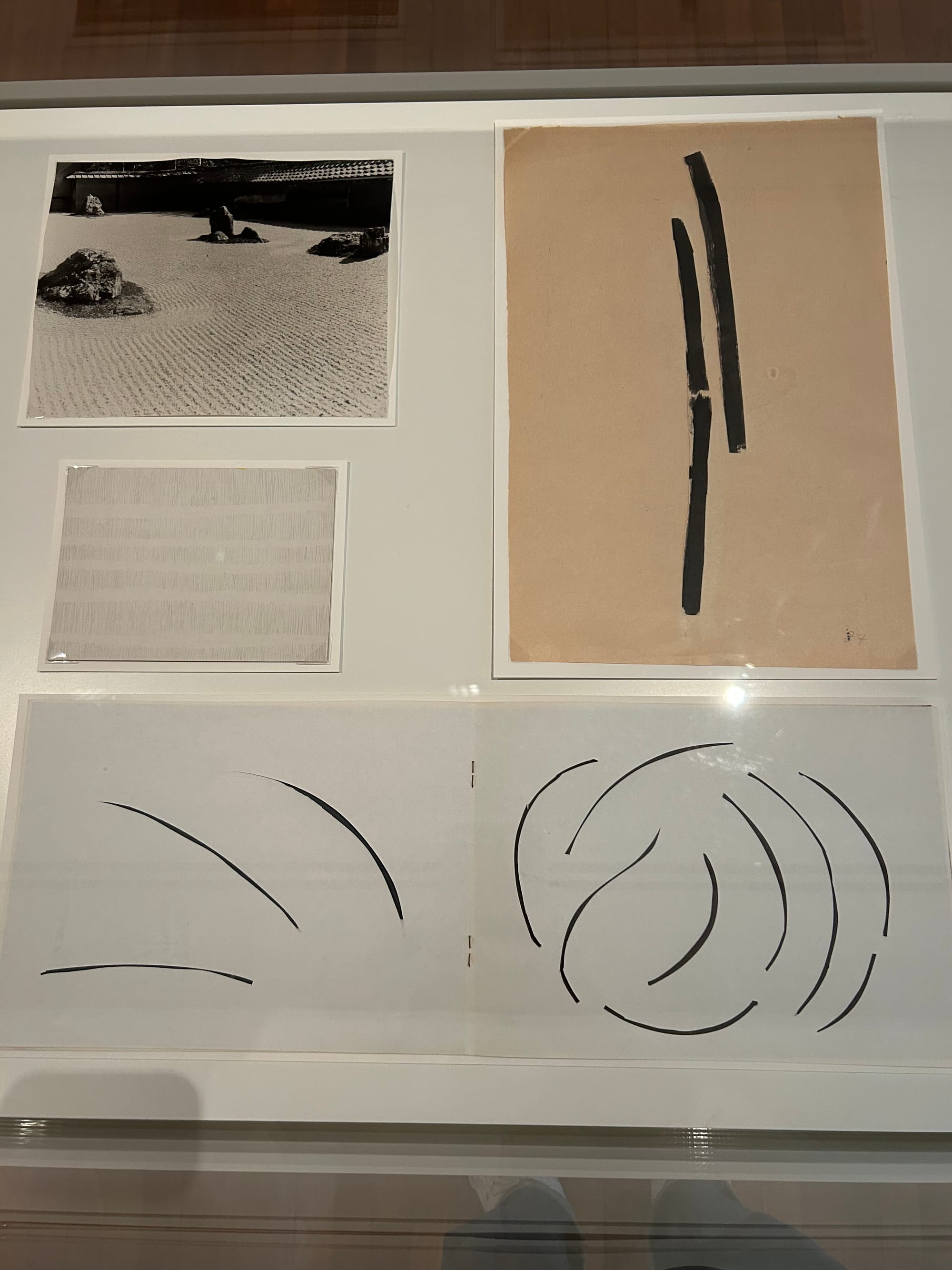

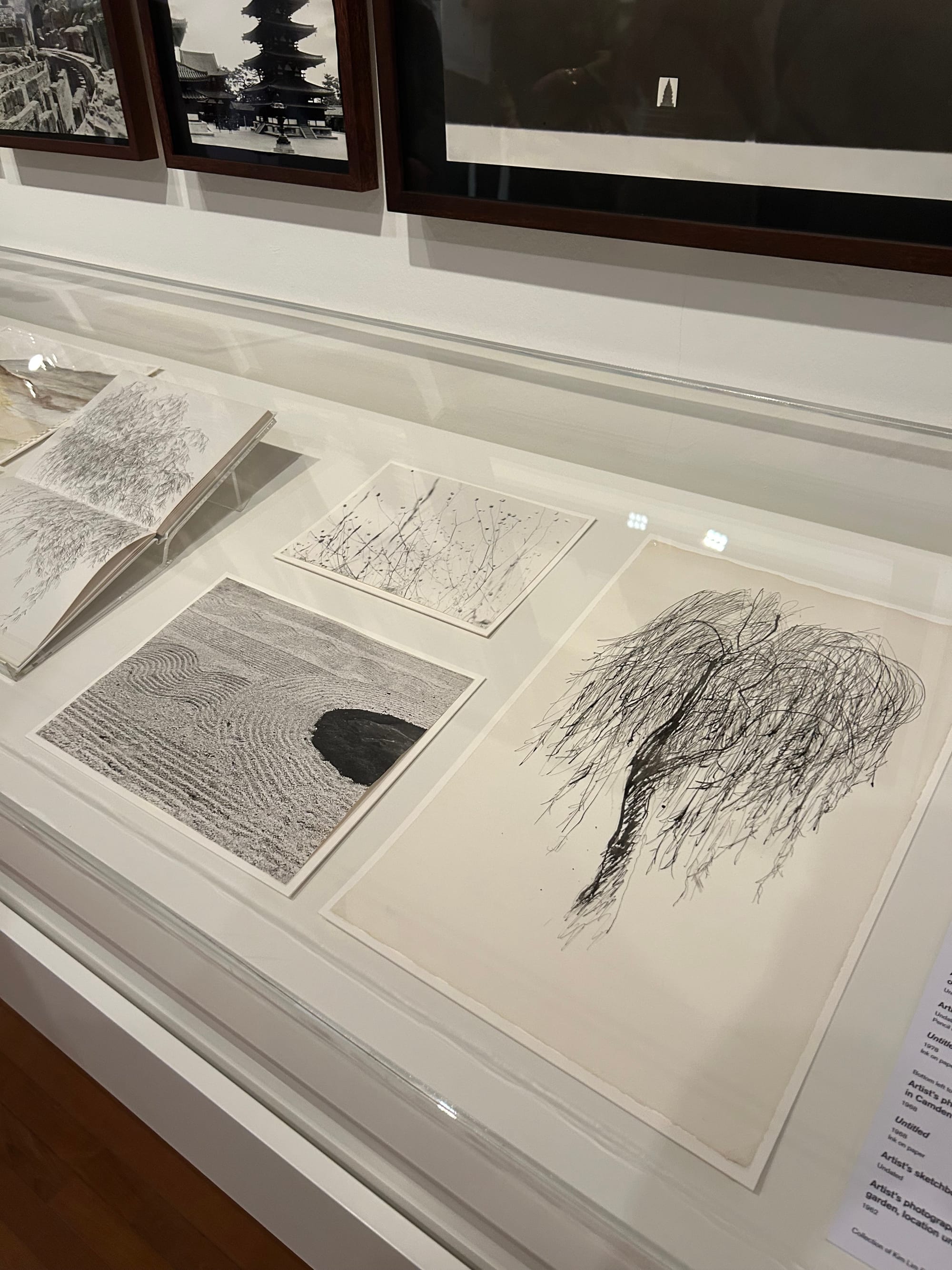

True to the title of the exhibition, some of the most touching moments on our tour of the show came in the spaces in between. The estate contributed a number of maquettes and archival material from the studio, materials that gained a particular resonance through Alex and Johnny’s familiarity. A wall of photographs became one of my favorites. At first glance, they looked like tourist snapshots. Upon closer examination, they revealed themselves as a highly curated collection of formal aspects of archaeological sites and monumental structures, many of which appear as references in Kim Lim’s work—from Stonehenge to Giza to Angkor Wat to Kyoto to the Cyclades. Then, with the added layer of personal narrative, they became a family photo album, opportunities for thinking about and sharing the aesthetic experience within the complex universe of the emotional life of a young family.

Alex and Johnny explained that these were study trips and working holidays, really, something that their parents started before they were born, seeking out direct access to art historical references that could be fruitful for their separate practices. Study trips but also honeymoons; study trips and then also family vacations. Growing up in this environment—and with a working stone carving facility for a backyard—it is no surprise that Alex and Johnny should have engaged with the creative life from a young age. To quote Alex:

There was an incredible respect and love between them [Kim Lim and William Turnbull]. You see in these amazing photos of them when they were young—both striking individuals. There was clearly a physical attraction but also a profound intellectual and artistic connection. They were drawn to each other not just as people but as artists, deeply inspired by each other’s work. Bill always said she was the best artist he knew, and I think he found as much inspiration in her work as she did in his. Though there are intersections in their art, their work remains distinct. … It’s fascinating that my parents came from such different backgrounds—Bill from a shipyard in Dundee and Kim from a well-off family in Singapore. Despite growing up in environments without art, they were somehow put onto this planet to do precisely what they did.

For all of these reasons I have always known that Kim Lim would play an important role in Nostos, but it was only when we arrived at the last chapter of the Singapore retrospective, the rooms about her later work in soft stone, that I started to understand how she would fit into this first essay. Titled “The Weight of Line,” this part of the exhibition draws explicit parallels between her mark-making practices at the foundation of her work with prints and the approach to form that we see in her best-known stone work made after 1979. (I say best-known, but in point of fact the resurgence of museum interest in her work has largely manifested itself in the other lesser-known bodies of work, particularly the wooden constructions, so perhaps this balance has already shifted.) Again the work came to life through Alex and Johnny, who described how their mother would go through cast-off blocks of stone from British quarries looking for a form she could work with, bringing them home to continue muscling them around in the garden. They pointed to a few specific lines that they found particularly weighty, instances of negative space inserted into reality. For me these lines and the phrase, “the weight of line,” called to mind something I have said about my dog’s collar: “the weight of belonging.” It’s a distinctly heavy chain, but she enjoys wearing it—whenever she hears someone pick it up off the counter she trots over and wags her tail and waits for it to be put back around her neck. My theory is that she bears its weight as a reminder of the affection and the mutual responsibility that comes with making a home together.

This weight of line brings us full circle to Alice Neel and Suzanne Valadon, to the distinct mark they share, the heavy dark outlines of their figures, one of the defining visual features of this practice of portraiture—a line that creates a relationship between the viewer and the viewed. In the case of Kim Lim I believe the weighted line holds together her practice across media, from the deep cuts in her stone sculpture to the physical weight of the pressed object that composes her prints. Throughout Lim’s work there is a play of rhythm and repetition, positive and negative space, a work of rocking back and forth to loosen and tighten, as if each time a form is repeated it settles further into a groove and deepens further its line. Art is a practice of discovering gravitas through experimentation.

Both of Kim Lim’s sons are highly creative people who have forged their own idiosyncratic practices and paths through art, music, film, and fashion across Europe and Asia. Alex Turnbull most recently completed the documentary Kim Lim: The Space Between, featuring a soundtrack by his brother Johnny Turnbull. Through this triangulation, they open up for all of us the rich matrix of ideas, forms, and love that they have spent their lives building.