Lives of the Artists: Adrian Wong (Part I)

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Lives of the Artists is a regular monthly interview column profiling contemporary artists, asking them to share the connections between their home lives and studio practices.

I am thrilled to share this conversation with Adrian Wong, someone who I have intense respect for as an artist, intellectual, and father. Adrian and I met in Hong Kong 15 years ago and have worked on a number of exhibitions, commissions, and other projects together. Also, our daughters once tried to smuggle a feral cat from the Saronic Gulf to Heathrow. This is the first half of our conversation, focusing on a body of video work in which Adrian traces stories of his family through Hong Kong.

Let’s start with your childhood. How did you find your way to art?

Adrian Wong: I went to school with a bunch of tech-focused, entrepreneurial people and started studying a lot of math and physics, but I got interested in the thinking behind these things so I switched to psychology and product design. I was in a master’s program in developmental psychology and got interested in art during my thesis research, when I had to spend a lot of time interacting with kids in an orphanage in Vanadzor, Armenia. The ruse I came up with was to pretend to be an art teacher. When I got back, I kept the art up and ended up with enough credits to get a degree in art alongside my work in psychology, and then when it was time to transition to a PhD I took a shot in the dark and applied for an MFA instead.

Looking at your practice, I see a few different stages, and one of them is this early interest in early childhood that comes out of your psychological research. And then as soon as you establish your studio in Hong Kong, the practice becomes very relational, and you’re working in collaboration with other people.

One of the things that led me away from the social sciences was the realization that the deeper I got into what I was doing and the better I got at what I was doing, the narrower my zone of activity became. If I started to pull things from outside, all of that was cut out by the time my research was approved. It was a complete accident that I came to Hong Kong, but I got really interested in a lot of different things, all of which were outside my area of expertise. The studio became a place where I could give myself license to explore things, to do the kinds of research that I found personally interesting, just to see what happened.

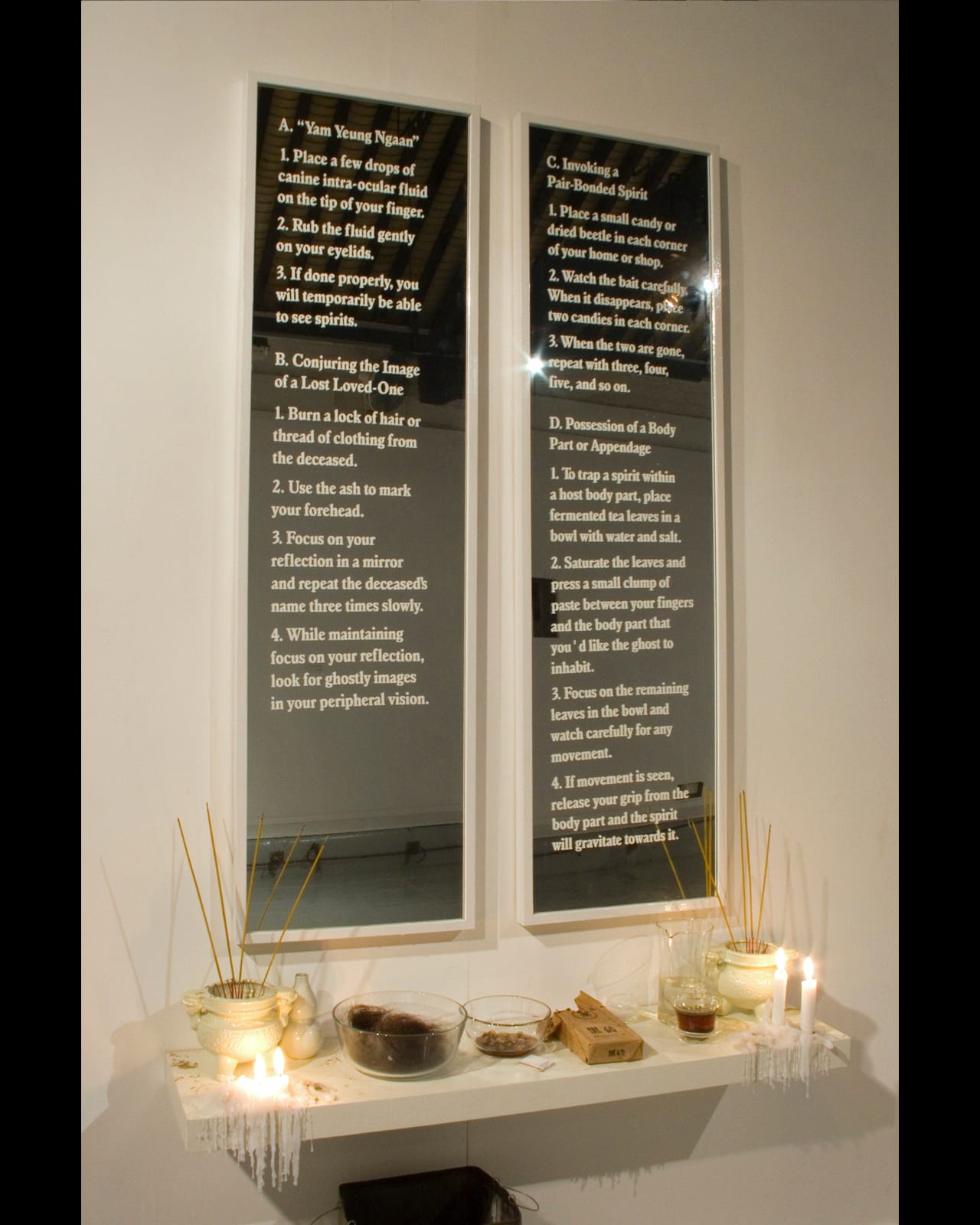

My first studio was awesome. It was a nightmarish wreck of a place. It was 4000 square feet, so in a space that big I could take the contents of my mind and allocate them real estate. There were whole sections of the studio dedicated to different branches of the practice, and they intermixed in space. I got really into vernacular architecture in Hong Kong. I was looking at local superstitions, doing a lot of stuff on ghosts. I had a section of the studio where I had set up a bunch of apparatuses to invoke spirits to come commune with me. There was a drum kit. It was the first moment where I was able to step outside of an academic context, to completely throw myself into thinking about my environment and process the world that I was living in.

And in a way you were using your practice to investigate or connect with your family history in Hong Kong, right?

I met someone in grad school who was on a teaching fellowship at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, so I just accidentally ended up in the place where my mother and father were born. My mother and father were both estranged from their families to the extent that I didn’t really know where I came from. My father’s side was a complete void for me, apart from a few comments that were made over the course of my childhood. I was partially raised by his mother, who never spoke about Hong Kong. It wasn’t until I got into that research that I realized how deep my roots were. For that first project I set out to rediscover a specific person that came up in my father’s family. This was my grandfather’s youngest brother, Calvin Wong, who was a Dick Clark-esque TV presenter in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. I was able to track him down, and found out that his son, my uncle Harry, was a celebrity magician in the 80s and 90s, so we ended up doing some work together. I art directed children’s theater as a side gig for a while for him, and acted in some of his productions.

Can you introduce the Sang Yat Fai Lok (2008) project?

That was the first proper show I had in Hong Kong. It was a two-person show at Para/Site, one of the first few shows that Tobias Berger put together when he came in. Calvin Wong had a TV program that aired for two decades in Hong Kong, and I thought it was a really interesting concept. It’s called Happy Birthday, and every Saturday he found a kid celebrating their birthday, and then threw them whatever kind of party they wanted. There would be some very surreal, strange requests, like a kid who loved ham so much that he wanted to have a ham party. And they would recruit a studio audience to play out this kid’s fantasy. When I finally tracked down my great-uncle Calvin, I found out that the show was never recorded—it was live from the studio to TVs in people’s homes and public parks. So I recreated an episode of the show, using it as a structure through which I could reinvestigate my connection to my family, with details drawn from what I learned about my father’s childhood, my grandfather’s childhood, the show and its role in my family.

Recently you’ve returned to researching your Hong Kong family with a project that loomed large in my understanding of your practice because I heard you talk about it for so many years. Can you describe your grandmother and how she entered your work?

I grew up in Park Forest, Illinois, which was the pinnacle of postwar suburbia. My grandmother lived most of her life in extraordinary privilege. My grandfather’s family fortune was vast. She gave birth 16 times. My mother was the 16th of those. Eight were viable, all eight are still alive. My mother’s oldest brother, my uncle Joseph, is over 100. My mom is 73. Her mother was not a traditional mother. I interviewed a lot of them for this project, and they barely knew her. They barely saw her. My mom has very few childhood memories of her mother. She was a socialite and spent most of her time throwing parties. My grandfather died relatively young. My grandmother did not have any formal education and got the keys to the kingdom after he passed, and spent decades burning through the family fortune. My mother’s siblings all expected some kind of inheritance, but she lived a very, very long time and ran out of money. My understanding is that she came to the United States because she couldn’t sustain herself, so she ended up landing with our family.

She took over the lower floor of our house and didn’t really want anything to do with us. She routinely wore these beautiful gowns and cheongsam, full face of makeup every day, and drifted around hardly acknowledging us, like a ghost living in our house. But she was fully immersed in daytime television, watching American soap operas religiously all day long. When she passed away she left a rack of composition notebooks, where she had kept notes on the soaps. For a long time, given the work that I was doing, I thought that if I had the opportunity to translate her notes, I would have some kind of outline of her version of the stories that she saw, and I thought I could get into that space and create a surrealistic soap opera based on her notes as a way of getting to know her better.

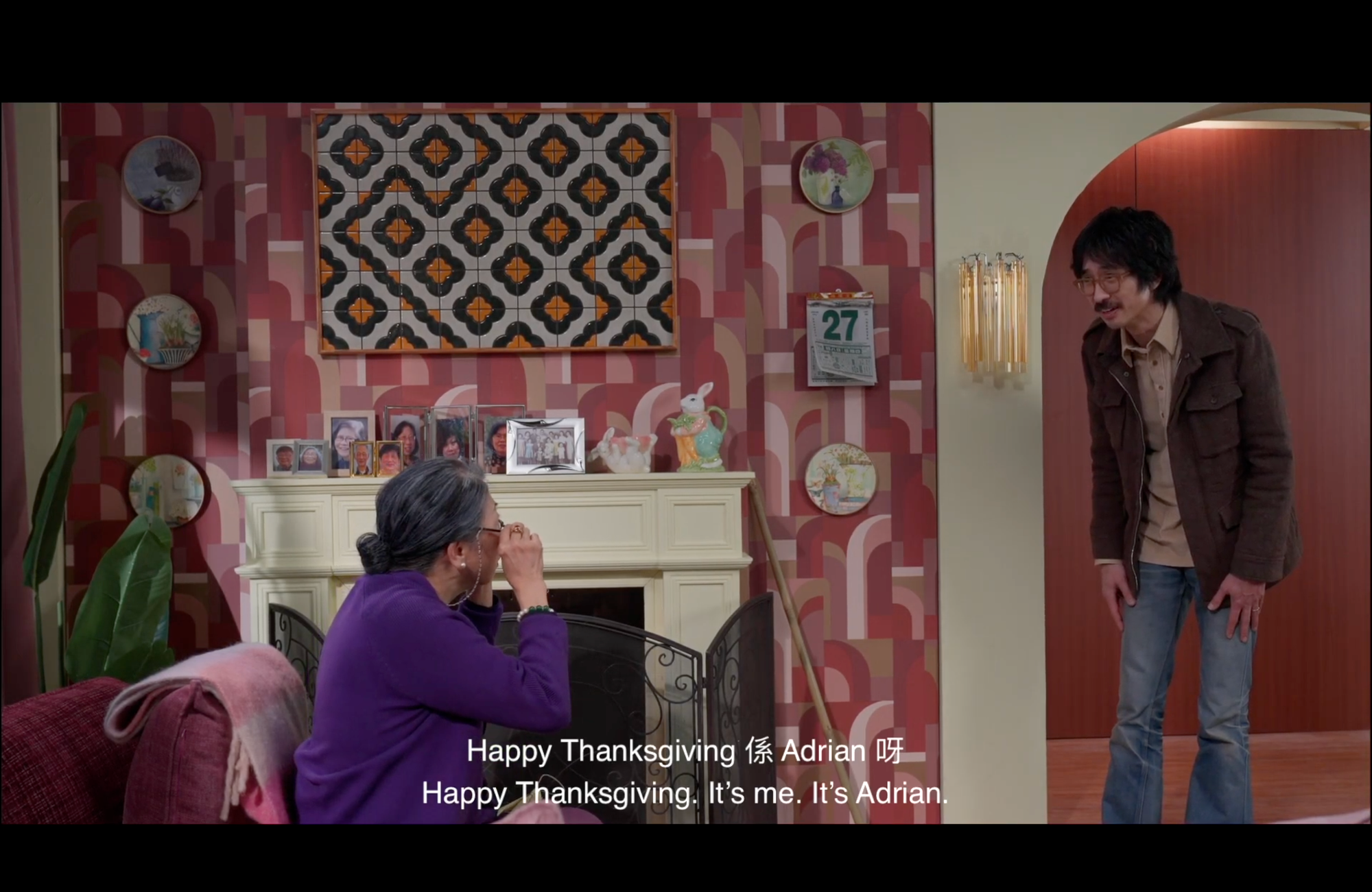

Unfortunately, when I was able to go back into those notes and have them translated, it was all gobbledygook. The project that I showed at Oil Street this spring mostly uses my recollections of that period of her life, but also tons of interviews with her kids, trying to get the bottom of what her life experience was like. Much like Sang Yat Fai Lok for my father’s side of the family, it became a loose retelling of my grandmother’s life from birth to affluence to her later years living with our family in suburban Illinois.

You’ve shown this in Hong Kong in a reconstruction of the sets.

AW: I replicated the sets, which were huge. I built four sets, with the help of an incredibly talented scenic designer, G Tsui. One set was a daipaidong, which is where she was first seen by my grandfather. My grandmother was from a lower-class family in Zhuhai, and while she was out buying the fabric for her annual new clothes at Chinese New Year, she was spotted by my grandfather, a little prince who saw her and said, “I want to marry her.” He picked her out from the crowd and arranged for a proposal to be delivered to her home. She was plucked from her family and never saw them again. There was a first wife from a notable family who was immediately demoted to maid. She worked administratively for the family and supervised the maids and drivers. My grandmother didn’t know she was actually his first wife until he died. Of all of the eight living children, not a single one of them could remember her name. Then there was a recreation of what her childhood home might have looked like, and finally a dual set split between my grandmother’s home in Hong Kong and our home in Chicago.