Lives of the Artists: Adrian Wong (Part II)

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Lives of the Artists is a regular monthly interview column profiling contemporary artists, asking them to share the connections between their home lives and studio practices.

Adrian Wong is an associate professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he teaches sculpture, and a father of three. This is the second half of our conversation, in which we resume discussing the body of video work in which he traces stories of his family through Hong Kong, and then move on to his approach to collaboration and finish by discussing his approach to parenting.

In the installation in Hong Kong we got to inhabit the mind palace of your grandmother, so to speak, and in a minute I want to ask about the mind palace of your daughter. But first, I understand the video installation is going to the Singapore Biennale this fall. What’s that going to look like?

The project I’m working on for the Singapore Biennale is related in structure, but the content is very different. As a kid I was told that my dad’s dad wrote music for movies. I know that he worked for Shaw Studios at one stage. It turns out they’re one of the sponsors of the Biennale, and when I mentioned the connection in a meeting, we found out that my grandfather composed the soundtrack to over 300 Shaw Brothers films. It turns out he was as famous as my uncle Calvin. When he was working, a lot of the kung fu films were actually composed of off-cuts of footage from other films, or they were shot without a script. You’d see who was available on set that day, bring them in, have them run around, fight, and argue—all recorded without audio. Then it would be edited together, my grandfather’s soundtrack serving as the backbone of the film, and only then would they get voice actors to overdub the action. In some sense these are unscripted silent films, and that structure struck me as exciting. It also helped me solve a budget problem. I hired stunt actors who look like the actors in the soap opera, and I’m going to edit the footage like a low-budget production would have done in the 1960s or 70s. We have a soundtrack, and we’re going to splice stunt footage and soap opera footage into a semi-sensible format according to the soundtrack. I’m going to write the script after the edit is done, then we’re going to get voice actors to overdub, and then we’re going to foley all the audio. It’s a composite film.

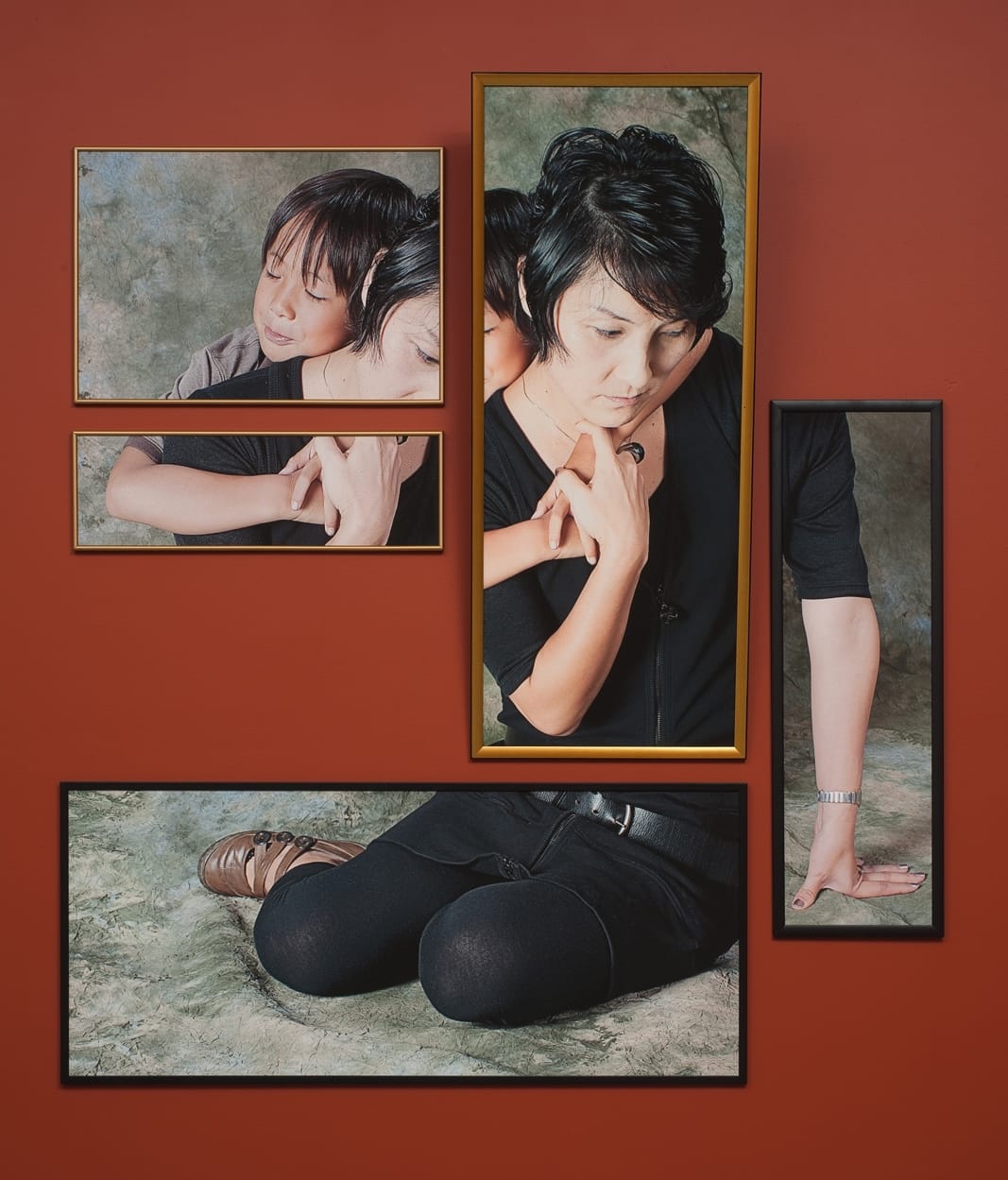

Let’s go back in time, to the end of your first cycle of work excavating your family history. You then turned to a series of family portraits.

I was thinking a lot about my childhood home. There were cheesy portraits of my family all over our house growing up, me and my sister dressed up and posing. I worked with David Boyce on this series of “Affective Portraits” (2010). I wanted to see what emotion looks like when it’s captured, so I went back into the psychological literature and looked at different categories of emotions, and the liminal spaces between the accepted emotions—where do they come from, how do we elicit them, and how perceptible are they in other people? We came up with two distinct sets of prompts. One set was completely fabricated, in that we were eliciting aspects of real emotions from people by showing them stimuli beforehand. In one simple one we cut up a tub full of onions, and the studio was so pungent that you started tearing up as soon as you came in. So one family you see their eyes watering. I think we also showed PETA videos and war footage. With one family we pissed them off on purpose by making them wait 45 minutes while we were getting ready, and so they were angry by the time we shot them.

But then in the more interesting portraits we used directed facial action, a technique used in emotions research where you train participants to control the muscles in their face. We would specifically direct people to contort their faces to represent stereotypical expressions of joy, sadness, disgust, anger, surprise. The underlying theory suggests that doing that can actually elicit emotion.

Aside from the human actors, you’ve had a lot of animals. Did they start out as pets or as collaborators?

All the animals came in for the work. It started with a conversation with my gallery in LA, because I’d done a run of disastrous collaborations that made it really hard because there was a long list of people who needed to be credited when I was selling work, and collectors were confused. The gallery said they wouldn’t give me another show until I produced something without collaborators. But this touchstone or connection to the outside has always been really important to me to have, an element of the unknown brought into the process. I came up with the idea that if I started collaborating with animals, there wouldn’t be anything to dispute. At first I wanted to collaborate with a beaver to chew through wood, but it was complicated and as I was on the phone with the wildlife sanctuary I happened to see our first rabbit in a store window, so I Googled whether rabbits chew significantly enough for sculpture. I bought Michael on the spot. I also got rats because I read that they are able to engage with toxic materials by rotating their front teeth. I also taught them to paint with treats and rewards. Then I figured out that parakeets’ poop changes color if you feed them different fruit and seed blends. Hamsters. Cats. A chinchilla.

More recently you’ve been collaborating with your children. Obviously, the looming question is, did they start out as children or collaborators?

When my daughter, Clementine, came along, she was a very high-need child. She slept very little and was very active, very curious, so it made sense for me to invite her to my studio and get her involved. It started off with her just being in a place where she could be creative, where she had art supplies and materials. She learned how to use tools very early. I would work on one side of the studio, and she would mess around on the other side. Over time that started to blur. She was able to see a lot of art at an early age, and she was able to spend a lot of time with other artists and other artists’ kids. She’s always had a real facility with making her ideas manifest, whether that’s through customizing toys or having rich imaginary worlds. There were a few early shows I involved Clementine in. Right when the pandemic hit we repurposed work in storage in my studio—she would have me pull things out of the storage and stack them up, add stuff to them, repaint things.

Let’s talk about the dream palace that we’ve been working on.

I mentioned that Clementine has had these sleeping issues. She had hypotonia as a child, which meant that she had a lot of issues with swallowing and digesting. She also had a pretty bad case of GERD, and so she couldn’t really sleep for longer than 90 minutes at a time until she was three, and had a lot of trouble falling asleep as well. A lot of those early years I would spend hours with her in bed, and we were working with a therapist who taught us a technique that seemed to work where, as she was falling asleep, I would start describing a scene. Usually we would start in a forest. There’s tall trees towering over your head. The ground is cold, but the air is warm. We’re stepping through the woods. You can hear the twigs snap underneath your feet, and you hear a sound. You look to the right. We would talk through this scenario so many times for so many years that we fell into a routine. It would end with us arriving at a castle that we would enter into and explore, or there would be constraints keeping us from getting into the castle. We had to sneak past guards. It dawned on me that we’d done this so many times that the space was coming into clear focus for both of us, that Clementine and I were visiting a private imaginary space that was ours and ours alone. For this forthcoming project, she and I sat down with architectural drafting software to create a concrete record of this place that only she and I visit, and will turn it into a place that other people can also enter into.

We’ve been talking about your family from the perspective of the practice. If you turn that around, could you share how you would describe your philosophy of parenting, or what sort of values you bring to the relationship between your home life and your studio life?

The huge luxury of being an artist is that I’m able to maintain fuzzy boundaries. I’m a professor at the Art Institute of Chicago. Some years I only teach one day a week, and some years I’m off for two months in the winter and four months in the summer. A lot of my practice is about engaging and exploring the world on my own terms. Parenting falls into that—I hope to share the values that I have that I attached to my practice with my daughter in that I don’t necessarily want to compartmentalize her engagement with the world as art or non-art. By incorporating her into my practice, getting her involved in the studio, collaborating with her, it’s a way of showing her that she can kind of make her own world. That’s a value that I hold dear: I want her to grow up knowing that her environment is malleable, that the way that she decides to engage with it is a matter of agency, and it’s not something that she has to accept on its face.