A Hole through Which the World May Penetrate

Why the spaces between SANAA's galleries matter most

I’m in Beijing this week working out of a gargantuan corporate office for a few days while my visa is being processed. I feel a bit disoriented as I’ve been bouncing around a lot of cities over the last months dealing with a lot of administrative work. I’ve spent a few weeks in Shenzhen exploring neighborhoods and visiting schools, last week with my daughter in tow, both of us trying to imagine what our lives there might be like and how we need to think of the relationship between home, work, school, and society. I’ve also passed through Hong Kong, Tainan, and Taichung, checking in on the museums on the way.

I was impressed with the new Taichung Art Museum, including the architecture by SANAA, but also the way that the programming grows along the pathways of the building. The galleries are beautiful, of course, but the life of the building happens in between them. There is a fantastic little reading library in the connecting foyer-bridge area between two of the galleries. And there are delightful little hidden doors that lead out the back ends of several of the galleries, opening into glass stairwells up or down into the rear entrances of other galleries.

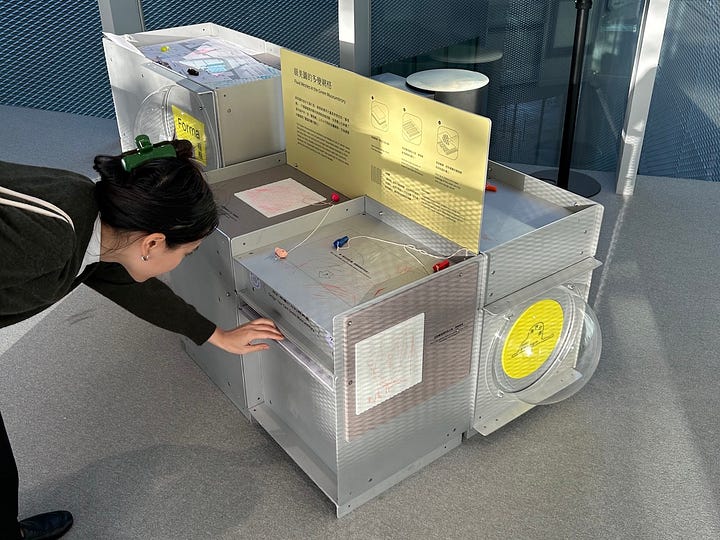

And, of special interest to us here, there are little activity areas for children scattered among the connecting bridges between galleries. These areas feel different from the galleries, more casual, more accepting of noise. It would be completely possible to make a quick pass through an exhibition space while children are occupied with one of these activities, or to break up the exhibition visit with stops at these stations.

On my second visit to the Taipei Biennial I brought my daughter with me to stop in at the Children’s Art Education Center in the basement of Taipei Fine Arts Museum, adjacent to Biennial projects by Ivana Basic and Musquiqui Chihying. The current project is “Whispers of Traces,” with work by Hsiao Yu-Chi, Liu Shu-Yu, and Delphine Pouille. The work is all quite strong, but they’ve separated the gallery into a distinct interactive zones and exhibition zones, which for me defeats the purpose of a space like this. You can feel the distinction in the space like an international border: everyone is clustered around the interactive installations, which are designed to a scale of cozy intimacy, and the “proper” works of art sit cold and lonely against higher, whiter walls. Where the differentiation among zones in the Taichung building creates a more inviting experience for families, her the latent lesson is that the art is better left undisturbed.

My winter reading project this year was finally finishing Martha Nussbaum’s Therapy of Desire, a super dense book about ethical philosophy in the Hellenistic era. I was first introduced to Nussbaum in college not as a classicist but as a theorist of civic life, and have only come around to her roots much more recently. Her understanding of Hellenistic ethics is about how philosophy emerges in the living of everyday life, and in particular through the mode of conversation and dialogue, and in creating an intellectual framework or understanding of the emotions or the passions. Hence, the therapy of desire:

Part of the sluggishness and carelessness of everyday life as it is normally lived is its failure to completely grasp its own experience and deeds, its failure to recognize and take stock of itself. The Stoic idea of learning is an idea of increasing vigilance and wakefulness, as the mind, increasingly rapid and alive, learns to repossess its own experiences from the fog of habit, convention, and forgetfulness.

It reminds me of something I read that Ian Cheng said in an interview: “The texture of life is a million little pinpricks of change.” Towards the end of the book, Nussbaum focuses on helping Stoicism find space for a more modern embrace of emotional life. As I would have imagined from her political work, she comes down on the side of love and the embrace of friendship, not as something to be feared but as a necessary condition for the life well lived:

Any person who loves is opening in the walls of self a hole through which the world may penetrate.

The most striking chapter, however, is not her conclusion but rather her close reading of Medea, in Euripides but particularly in Seneca, avatar of Stoicism. Together we are enthralled by the passions—pure sublimation—inspired by love, even love at its most jealous and possessive. As Jason says to Medea:

Go aloft through the deep spaces of heaven and bear witness that where you travel there are no gods.

I haven’t read any of the modern retellings of Medea, nor have I ever seen any of the stage adaptations, so I was thrilled to read that Natalie Hynes has just released her own version in No Friend to This House. I heard her speak about Medea on one of my favorite podcasts, The Ancients, just as I was finishing the Therapy of Desire, which has been out for 32 years and my copy of which I picked up in Shanghai years ago. It’s the kind of coincidence that means nothing and yet feels like everything when you’re traveling through the deep spaces of heaven where there are no gods.

While I’ve been reading this my daughter has been swapping back and forth between A Macrohistory of the Communist World and a selection of Russian existentialism. She’s looking forward to our move to Shenzhen, which we’re conceptualizing as a laboratory for actually existing fully automated luxury communism.

Later this week and over the weekend I’m planning on seeing a few exhibitions that I’ve very much been looking forward to, particularly Liang Yuanwei’s new solo exhibition and Yang Fudong’s UCCA show. Liang Yuanwei was one of the first artists I had the pleasured of working with fresh out of school when I was writing the press releases at Pi Li’s gallery. The exhibition “BLDG115 RM1904” consisted of around a dozen paintings from her “Piece of Life” series, each one an attentively worked textile pattern fading gently from top to bottom, one painting on each side of a handful of freestanding walls scattered around the cavernous space. Having the opportunity to sit with her and listen to the way she thought about her work and then try to translate it for the public was one of the formative moments of my early career, along with projects by Qiu Xiaofei and Yang Xinguang shortly before and after. I’ll write a bit about the Beijing exhibitions on Instagram.

I was in Shenzhen for Christmas this year, so I threw a Christmas dinner for friends and family back in Taipei on a random date in January between trips. There is no pleasure like the warmth of brilliant loving people around the table.