A Toy is a Toy. Art is a Reality.

At a doll party with Ghislaine Leung, Precious Okoyomon, Sally Mann, and Cosima von Bonin

Editorial: A Toy is a Toy. Art is a Reality.

I’ve lifted that title from Louise Bourgeois writing on Freud:

A toy is fine, but it is only a toy. It’s not a reality. Art is a reality.

There’s a surprising amount of stuffed animal art on exhibit at the moment. Stuffed animals are such charged objects, sitting close to us in moments of weakness and vulnerability, speaking to parts of ourselves that we don’t typically take outside the house. When artists do so, we are offered an illuminating window into the making of childhood: how artists deal with their children on a logistical level, how the labor conditions of making art sit with the labor conditions of raising children, and how art gets made at all on a psychological level.

When I was a kid I was supposed to be careful with stuffed animals because of my asthma. Weirdly, I don’t remember my favorite stuffed animal—I remember there was one, and I can picture its role in my life in parallel with my brother’s favorite, which I recall as clear as day (peanut butter bear). I need to ask him to jog my memory about mine. I remember buying a stuffed squirrel on skis at the hospital gift shop for my new baby brother when he was born. My daughter has had many favorites: a succession of baby seals, one giant oversized pink thing that she referred to as her big sister, and more recently one of those custom facsimiles of our dog, Brownie. She particularly likes them in series: identical Jellycat bunny patterns in different colors, and Labubus that sometimes make it into bed with her. Repetition is a balm on the soul, as we shall see in the work of several artists I want to talk about today.

Field Trip: Ghislaine Leung at Cabinet

Ghislaine Leung’s exhibition at Cabinet in Vauxhall was advertised very minimally. The first email contained this close-up photograph of a rainbow gradient stuffed cat. The second email, conveying the timing of the opening, included just the following text:

It is the holidays. I am working. I ask my daughter to play with her bear for a minute. She’s making a dress out of kitchen roll and hairbands. I put my work away. I start back to work. I am not paid for either work. There will be no fee for this show. No guarantee it will sell. If it sells I will be paid, if it doesn’t I will not. Perhaps other things will happen. Perhaps they won’t. So. We all work. Some are paid. Some are not. It’s just how it is I am told. It is the risk you take. I know this. We all know this. Everyone knows. So. Here. I will take my risk. I will work my hours. I will know my burn time. I will let go so I can hold on. I will stop so I can continue. I will let what is already done, and being done, be enough. I do not know if it will be enough. I am frightened. I am in love. I have nothing and everything left to give.

Cabinet is one of those galleries who tends towards the minimal, with one of those wonky websites that feels like it was put together by hand in HTML when the gallery was founded in the 1990s. It’s elegant, in a way. It speaks for itself. Ghislaine is also an artist who prefers that the work speaks for itself, in that the work typically consists of itself speaking, a speech-act that is also an art-work. For the past decade her practice has involved composing conceptual scores that are executed by the space or institution.

By way of illustration, this exhibition shares a title with another solo that ran at Neuer Berliner Kunstverein over the summer: “Reproductions.” That solo contained two scores and five editions. The score of Budgets reads: “The exhibition budget is displayed.” The score of Maintenance reads: “The exhibition space is left as it is.” Ghislaine authors the scores, and institutional curators interpret and perform them. In the case of the latter score, for instance, the curators decided to leave in place some of the residue of the preceding exhibition, and not to clean the exhibition during the course of “Reproductions.” Other curators might interpret this score differently. The five other works, each titled n.b.k. Edition, consists of decommissioned infrastructural objects like lighting fixtures that Ghislaine moved from storage into the exhibition space, turning them into editioned art objects that can be sold for fundraising purposes. What you see, in the exhibition, is this: piles of lights on the floor and a spreadsheet printed on the wall. Thus spake Ghislaine.

Her text introducing the Berlin exhibition runs in parallel to the London text: “It is spring. The blossom is on the trees. My daughter dances in the kitchen …” She has turned the cumulative actions of being an artist, the actions of being a person who is working as an artist, into the practice of an artist, into the art. Is there less invention in this autofiction? Or does the invention, the creative act, simply occur at an earlier moment in the cognitive process.

Several artists are working in this area, with legacies of dematerialized conceptual art and institutional critique wedded to our post-identitarian political moment. Aside from Ghislaine, the most prominent among them might be Cameron Rowland, who is currently in the news because a flag from Martinique that is a manifestation of his work has been removed from the facade of the Palais de Tokyo. Collectively, these artists are interested in labor and in the material structure of how art is circulated, seen, and understood.

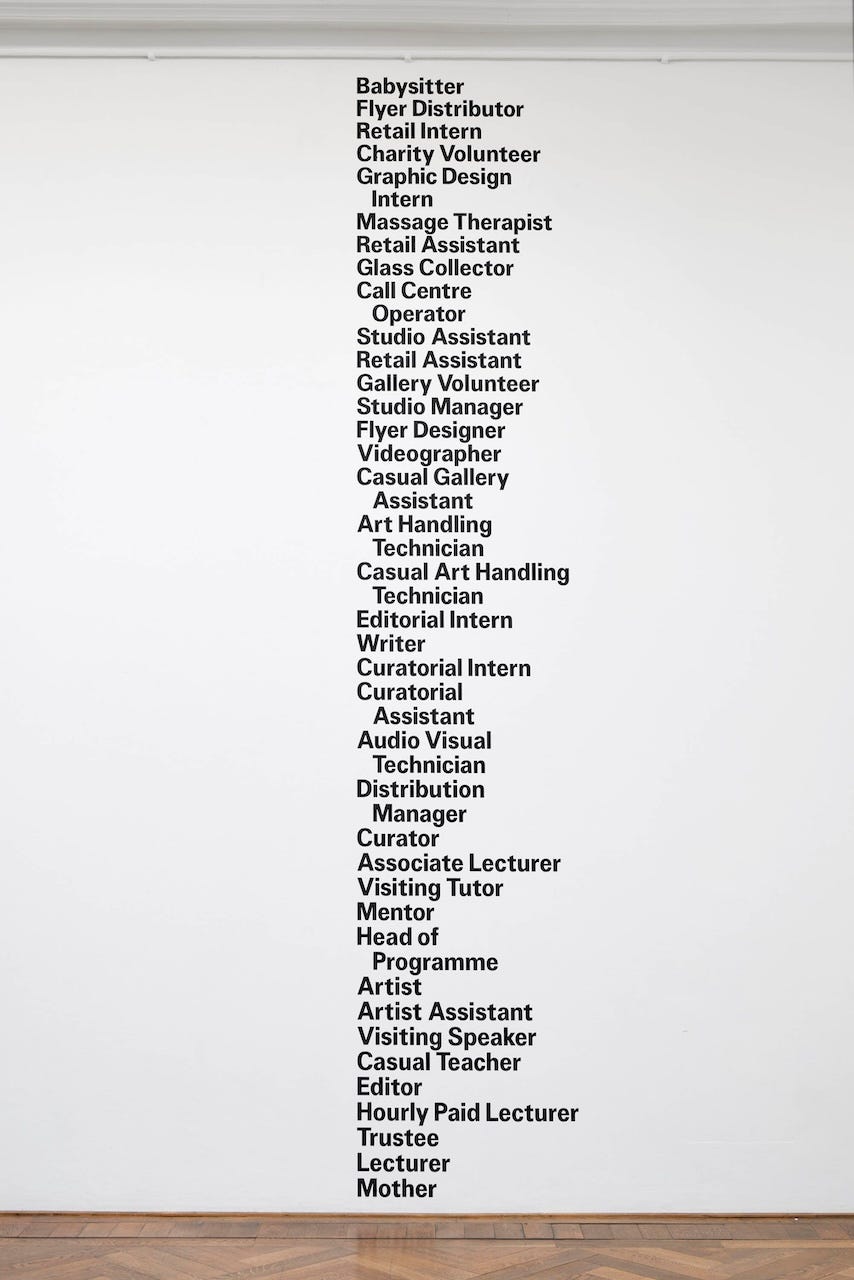

As we see in Ghislaine’s introductions to her two “Reproductions” exhibitions, motherhood is an important part of how she considers her labor—as an artist, as a mother, and as a member of society. Just one part, of course. In a wall painting titled Jobs that was also repeated on the exhibition poster for “Commitments,” her solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel last year, her many commitments are listed in full. Mother comes last. I suspect their order to be chronological, but as this is not specified in the score I remain unsure. Mothering, perhaps, is the last thing one ever does. “Commitments” also included a pair of Albers-esque geometric wall paintings. The score to Care reads:

A wall is equivalent to all the days in a year. The 2016 child care hours the artist would need to cover working full time are shown as a banana rectangle. The 1140 free childcare hours supported by the UK government are shown inset as a cobalt square.

Aesthetically, this approach is necessarily dry. It is the visual language of the spreadsheet. The practice actually incorporated toys for a number of years before the artist became a mother. The work itself was the grid, the score, the raison d’etre. The toys were a weird visual remnant of the point being made. But there is a hidden poetry here as well. Ghislaine’s book Bosses begins in address to her daughter:

I’m tired of hiding everything about it all. Hiding becomes intolerable at some point. My desire to mask my situation is a disadvantage to the understanding of the work. Love is an action, it is learnt, and must be maintained. You are my heart in the world, you told me. I did not know how to love, or I had forgotten. Freedom is often conflated with autonomy, but dependence is perhaps less the incarcerator than the liberator. I am free with support, not without. I am big and you are small, you say. But I am as dependent as you are and this is not an issue because care exists socially, is required and reciprocated a thousand times over in a moment. That I fail to acknowledge this is the price I pay when I misattribute agency to individual life, as identity in a monological sense, in my vivid financialised disincorporated life. Because love is not romance but trust. And trust is not an attribute of the adult.

Perhaps it is only my personal bias, but the emotional power of this framing hits me harder than the spreadsheet aesthetics, and returns me to the exhibition budgets in a new frame of mind. There are stakes to what we do. I’ll close on what is probably Ghislaine’s most iconic score, titled Four Years in Ten Years in Twenty Years, which reads in full:

A three-tier anniversary cake to mark four years of being a mother, ten years of being an artist, and twenty years with her partner.

Field Trip: Precious Okoyomon at Mendes Wood DM

I want to pick up on the last line of the first paragraph of Ghislaine’s book, when she says that “trust is not an attribute of the adult,” and read it again in the context of Precious Okoyomon’s solo exhibition at Mendes Wood DM in Paris, “It’s important to have ur fangs out at the end of the world.” It is exciting to pair these two artists together in commercial gallery solo exhibitions because they are so committed to the practice of art outside of the commercial gallery sector. The mind struggles to imagine what kind of objects might potentially even be for sale.

And yet, there is one distinct difference: you will find no photographs of Ghislaine’s exhibition on Instagram. As of this writing, literally not a single image. Cabinet is not on Instagram. Ghislaine is not on Instagram. Her face is not on the internet. I waded deep into the Vauxhall geotags. Nothing. Precious’s exhibition, on the other hand, you will have seen everywhere, even if you didn’t know it was her work. It’s instantly iconic, and almost assured to show up in the next round of QAnon cultural crusades alongside Demna, Borremans, and Matthew Barney.

These are the creepiest of stuffed animals: slick, oversized teddy bears with flames in their eyes, wearing translucent frilly couture panties, pinning each other down amorously or violently—or totally innocently. Precious’s show is about the Venn diagram of innocence and knowingness, described as “oneiric inner worlds where the childlike and the erotic become paths to understanding how fragility can be a radical condition of care and transformation.” The labor of being a childhood, juxtaposed beneath the labor of mothering.

This takes me back to the Lauren Oyler piece on vulnerability that we read last week, and Lauren’s preference for the recognition of weakness in place of the performance of vulnerability, and for un-gendering the whole thing, seeing systemic problems as systemic rather than as part of a gendered identity.

Precious has been working with things that look like kids’ toys for a while. She sees the bears as a reservoir of the “innocence, violence, submission, play” that is the stuff of childhood. They often appear in horticultural configurations, like Beloved, the animatronic bear in the same couture lingerie breathing and blinking, passed out at the heart of a garden of poisonous plants. Smaller toys started appearing more recently. Mendes Wood had a group of them at Basel last week, captioned as “artist-made children’s toys with taxidermied bird wings, rope, motors.” They are equally adorable and horrifying.

Ghislaine and Precious show us two sides to childhood, two sides to the practices of love that protect and deform us as we try to grow into the world alongside the flawed and broken people around us who can only try their best. One analytical, one evocative, both reaching towards the sublime of human experience in touching on the grittier corners of the ways we love. Love is work. Work not as in labor, not as in effort; work as in art work.

Also like Ghislaine, Precious has a publishing practice. Her poetry collection But Did You Die? has become one of my very favorites. She speaks of the bears:

Invocation of the Bears They plotted in play In love to dream to love in a way that was freedom Outside of the apocalyptic visions of utopia Open something in the wound DREAMS RUINED THE DESIRE ECONOMY

Links: Sally Mann and Cosima von Bonin

“Sally Mann,” on Great Women Artists, plus

“Demystifying the Life of an Artist, the Sally Mann Way,” in the New York Times

Katy Hessel interviews Sally Mann, who has recently published a second memoir titled Art Work: On the Creative Life. Sally is a particularly productive speaker on the topic for how closely she has drawn from her family life and domestic life in her practice as a photographer. Her photographs of her children in everyday life have been a flashpoint of the culture wars across several decades now, first in the 1990s when she first published Immediate Family and now, again this year, when police in Fort Worth, Texas, confiscated the same photographs from an exhibition at that city’s Modern Art Museum. Some 15 years ago, she shot another body of work on the body of her husband, Larry, who had then recently been diagnosed with muscular dystrophy. She has continued to shoot him as his condition deteriorates, with new images coming in her next Gagosian exhibition in 2027.

“Cosima von Bonin’s Works Are Dumb. That’s the Point,” in ArtReview

JJ Charlesworth writes about yet another exhibition toying with stuffed animals this season, in this case Cosima von Bonin in her first London solo exhibition at Raven Row. His opening line says it all: “Plushes, plushies everywhere.” Von Bonin’s soft toys, often on plinths on the corners of art fairs booths, are one body of work that has consistently evaded me, in the sense that I’ve never quite been able to figure out how to place them. In a sense it feels of a piece with the Kippenberger scene, and in another sense it seems to be taking the piss. Either way I appreciate them as the manifestations of flaccidity that they are.