Conch Fritters and Bee Stings

Marlene Dumas, Margarita Liberaki, Celine Song, and more

Editor’s Note: Conch Fritters and Bee Stings

Editor’s Note is a regular column introducing topics, themes, and frameworks from a personal perspective.

Logically: a conch fritter is the opposite of a bee sting. I came to this impossible conclusion spending time with my family on the road this summer. When your summers consist of tumbling around the undergrowth, eating sun-warmed berries straight from the bush, bee stings are a fact of life. This August I was in Maine during that magical week of the summer when blueberries, raspberries, and blackberries are all ripe at the same time. I collected them hand over hand so enthusiastically that I found myself competing with bees loosely swarming the bushes, at times accidentally knocking them out of my way. No stings. It must be 25 years or more since the last time I was stung by a bee. When you spend your winters messing about on the decks of boats and up and down the docks of marinas in Florida and the Bahamas, conch fritters are equally a fact of life. Sometimes a little too spicy, always a little too hot, but invariably on the menu. It will have been 25 years or more since my last conch fritter. As a child, bee stings are something you hope to avoid, but nevertheless accept as the cost of doing the sweet, sweet business of berry picking, tree climbing, and general woodsy mayhem. Conch fritters are something you assume will proceed apace indefinitely into the future, an uninterrupted stream of spongy, chewy goodness that will pop up on every menu from here to eternity.

Needless to say I haven’t lived on a boat in a while, and I don’t dine on as many docks as I’d like to. When I got back to Taipei a giant blue mud dauber had taken up residence in the kitchen, but after a couple days we were able to work her out the door without a sting. Here I am, more or less an adult: minimal bee stings, minimal conch fritters. Ample berries, to be fair.

We are notoriously bad at predicting what will make us happy in the future. We think we know, but we are almost always wrong. My philosophy of life has become a lot more about acceptance than planning, almost to the point of chaos. Being in a committed, loving partnership with the right person brings color to the corners of our lives in unexpected ways, and yet planning for what the right kind of person means and attempting to seek them out almost always backfires. Finding a sense of purpose in the work that structures our days creates a scaffold of meaning that gives weight to everything we do, but it’s not the kind of purpose that can be written out in a mission statement. So many of our choices, especially the ones that feel like the big ones, don’t actually matter—at least not in the life-defining ways we expect them to. The things that do reliably make us happy tend to be the places where we can pursue the inner work within and between the milestones: coming to terms with ourselves, building a sense of home, cultivating connection, picking berries, caring for others, diving for conch.

Icon: Marlene Dumas

Icon is a regular column pairing canonical works of art and quotations from pioneering figures in the history of art and life.

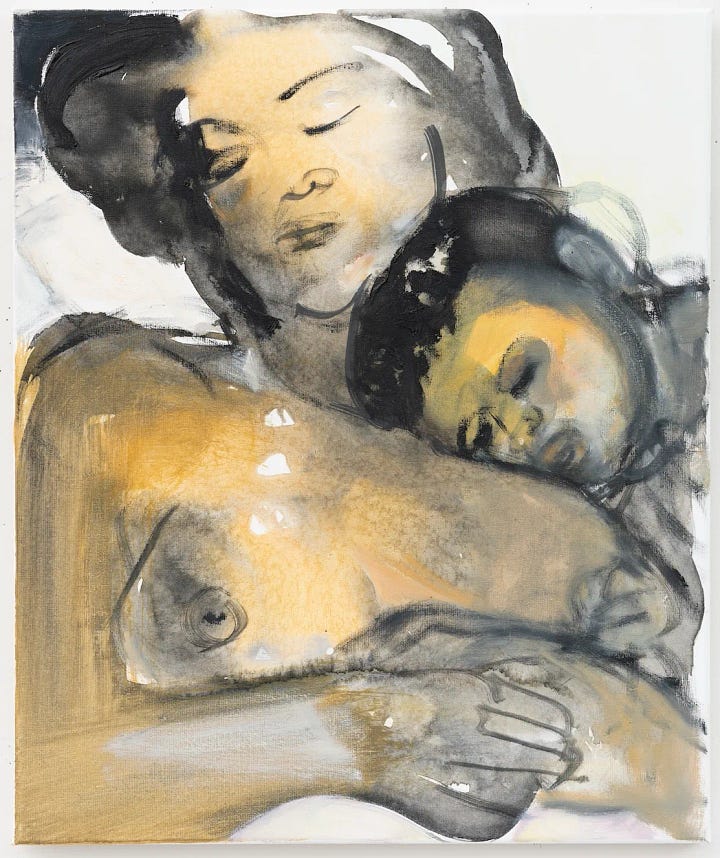

“Motherhood is a shock.”

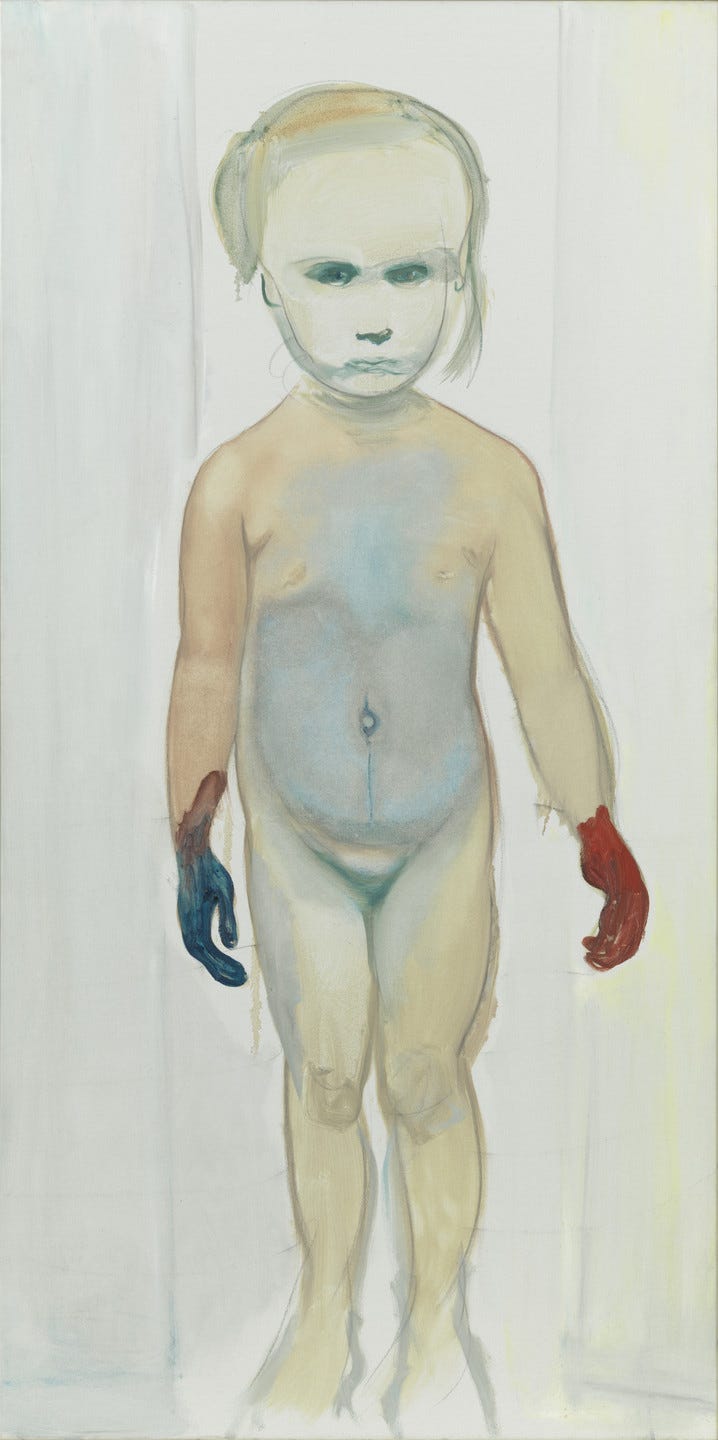

This painting is titled The Painter, and is based on a photograph of Marlene Dumas’s daughter coming in from finger painting in the garden. The painting is two meters tall and one meter wide. Hung even slightly off the ground, the figure dwarfs the viewer. There is something unsettling about the body of a baby in the proportions of an adult—think of Charles Ray’s Family Romance, coincidentally executed around the same time as The Painter.

Marlene introduces The Painter:

Historically it was always the male artist who was the painter and his model the female. Here we have a female child (the source my daughter) taking the main role. She painted herself. The model becomes the artist.

She painted herself. Marlene Dumas is one of the greatest painters of our age. She is the greatest living painter of motherhood. She is also the greatest living painter of pornography [compositions from pornographic source images]. The fact that she is such a titan of her medium means that she is automatically “the greatest living painter of ______,” where the blank represents whatever she might choose to paint. And yet I can’t help but think that the slipperiness of her bodies, the tactility of their surfaces, comes from a place of profound awareness of the ties between all of these things, the paint and the skin and the self and the other and pleasure and pain and the future and desire and death, that part of her greatness actually comes from her willingness to dig into the creative properties of the body.

Marlene became a mother for the first time at the age of 36 in 1989 and was struck by the body horror and responsibility of the new baby. As she said in the audio guide to her MoMA exhibition:

People said that my babies looked quite horrific and alien, but actually all I did was something that is often done in art, you know, changing the scale of smaller things into very big things.

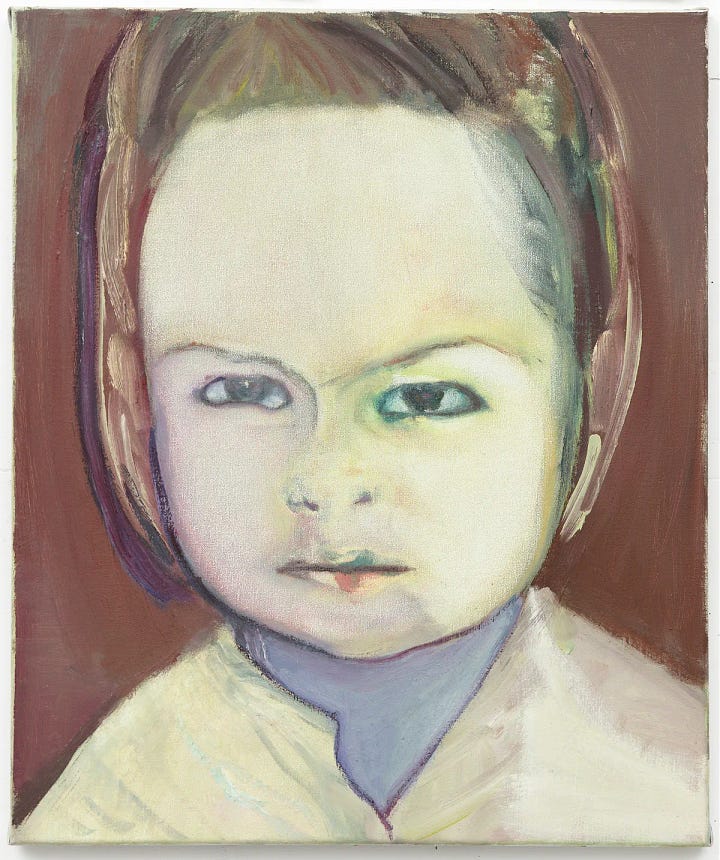

In the mid-1990s Marlene created a series of paintings on paper in collaboration with her daughter, Helena, who then would have been around five or seven years old. She has said:

Helena decorated, improved and worked on my black and white drawings with colour when she was six years old. She found them a bit too boring. I was her underground. Unlike Arnulf Rainer working on photographs, she worked ‘against’ me rather. I allowed her to play with my drawings so I could do other work. This wasn’t set up as an art project in the first place. She ‘re-casted’ my models into her own stories. One was kidnapped, she said, and walked into a horse.

On view at the Museum of Cycladic Art this summer are paintings of Helena as a toddler as well as Helena as a grown woman with her own daughter, Eden.

Sexuality, pregnancy, childhood, and death are some of the parallel lines that track through Marlene’s work over the past half century. It might be this disconcerting suite of four paintings that captures the darkly existential joy of what she brings to painting better than any other. Here stands Helena again, maybe three years old, mischievous and defiant and innocent and knowing, flanked by three skeletons with their own dolls and children. The painter’s child is the only memento mori she needs.

I am the third person

observing the bad marriage

between art and life

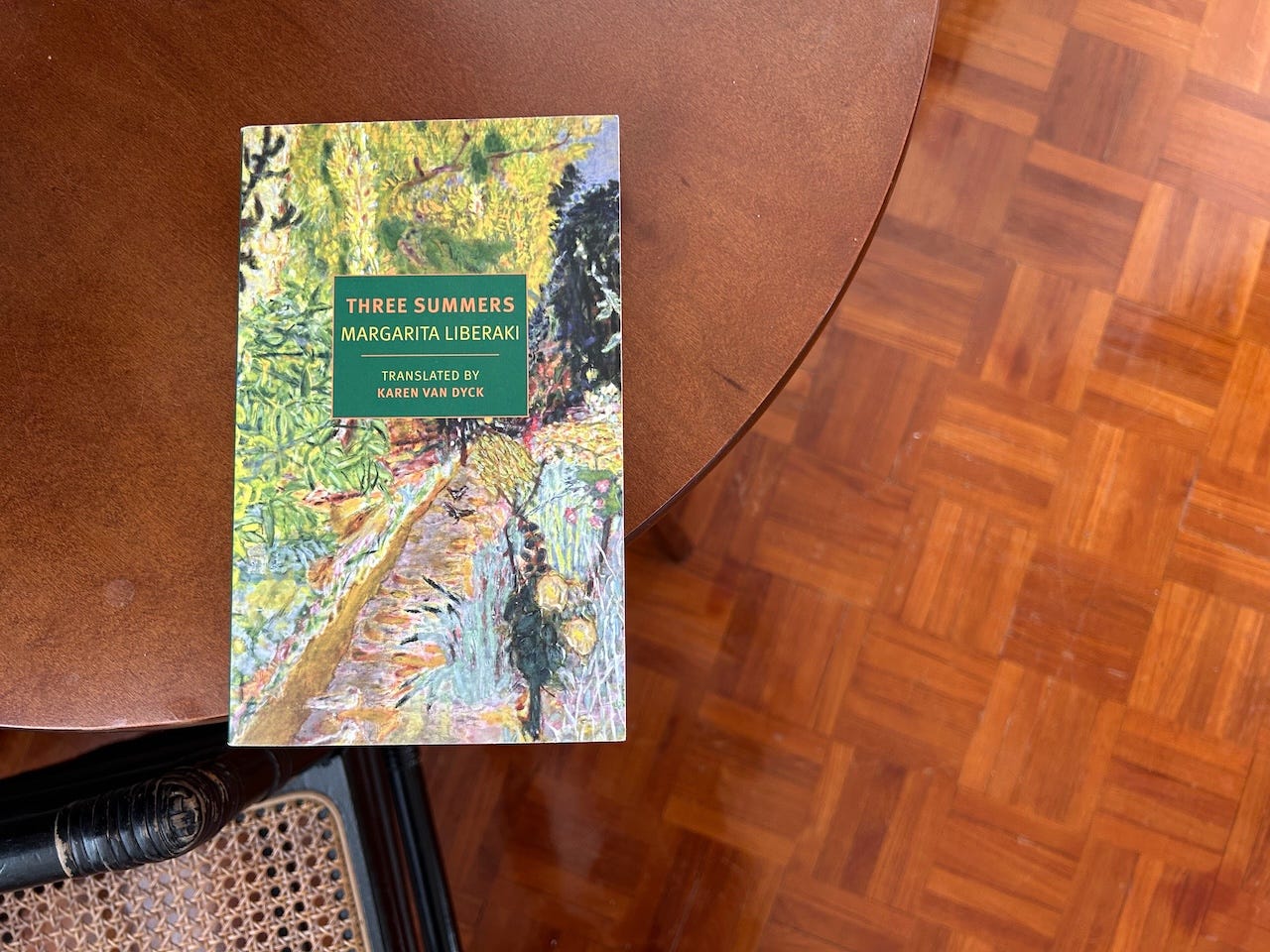

Book Report: Three Summers

Book Report is a regular column that reads books for, by, and about artist parents.

With apologies to those who have to share the beach, deck, or cabin with me, my embarrassing travel habit is reading the book about the place. A few weeks ago I picked up a copy of Margarita Liberaki’s Three Summers, which is set in the affluent outskirts of Athens in the 1930s. Liberaki tells the story of three sisters over three summers: one who marries and has a baby, one who rejects men for the company of horses and an aunt, and one who finds herself deciding between pursuing the love of an astronomer and writing a novel about seeing the world. In her translator’s note, Karen van Dyck speaks to the autobiographical aspects of this triangle, and how the third sister (the protagonist and narrator of the novel, of course) represents a synthesis between the positions of the first two sisters, who respectively represent the domestic family life and the creative life of the artist. In real life, Liberaki only had one sister.

The concluding chapters of the book are rife with fun meta-fictional reflections on the nature of storytelling and the blurry area where life runs into narrative. It all ends a bit too abruptly for me, but the material that leads up to the revelation that the sister will indeed sublimate her yearning for love into literature is beautiful:

Of course all voyages are really one—the voyage. And in this way Andreas, by leaving some days from his life in Barcelona, some in Le Havre, some in Athens, carves a single, unique line. That’s the line I want to find and express, the line that represents the essence of his life and that perhaps even he doesn’t know about. I want to be like the artist who, in a moment of inspiration, captures a resemblance, expressing the whole person, the person at all times in one painting. I once saw a painting like that. It was of a woman. But you could also say it was about submission. Submission was characteristic of that woman, but in her life it wasn’t obvious, it didn't reveal itself all at once, instead it spread itself among her various gestures, each one quite distinct from the next. It wasn’t condensed the way it was in the portrait, which managed to combine a submissive look from one day with the submissive movement of a hand from another day, and so on.

That leading line might even need to enter the poetic pantheon of my sign-offs:

Cavafy: “Hope your road is a long one”

Seferis: “The first thing god made is the long journey”

Liberaki: “All voyages are really one”

Projections: Materialists and Black Bag

Projections is a regular column on films that touch on living in a creative family.

I’ve been a big fan of Celine Song since Past Lives, which I watched in bed as a little wallowing treat on my birthday two years ago, so I was pretty heavily invested in the discourse around Materialists leading up to its release. I read a handful of reviews before I was able to see it, and somehow from the reviews I was led to believe that cynicism won out and the film came down on the side of money over all. This is not the case; Celine is a romantic in spite of everything. Which is important for our purposes because, in Materialists, this involves the protagonist choosing the struggling artist over the financier in spite of everything, choosing the compulsions of love over playing the game. Celine’s real-life partner is the writer Justin Kuritzkes; like the couple in Past Lives, they met on an artists’ residency.

If pushed I would say that I find this situation more interesting, the nitty gritty of how creative people choose to make a life together, how they choose to channel all of that energy—all of that storytelling. In a way these movies are the answer. The other one I enjoyed recently was Black Bag, in which Michael Fassbender and Cate Blanchett play married spies who have to decide how much they can trust each other: how much to share and how much to keep in the black bag. This is a beautiful artistic romance. They may be spies instead of actors and directors, but the creative intellectual energy they bring to their work is so much about invention and devotion. In both Materialists and Black Bag, love wins. Art wins. I heard someone say recently that the way to balance ambition and contentment is by linking them through a practice of devotion These movies get that.

Links: Children’s Museum Exhibitions, Cooking for Gertrude Stein, Psychoanalyzing Romance, La Gonette, and Gwen John

“Not Just for Kids,” in Monocle

Kimberly Bradley asks if child-focused exhibitions might actually be the future of museums. She looks at exhibitions like “For Children,” “Radical Playgrounds,” and “The Enchanted Castle,” as well as the Young V&A, suggesting that they create inclusive forms of public space and reach out to the audiences and decision-makers of the future. I agree with all of these points and am glad to see this trend being picked up in the media. Personally I feel that positioning public art in this way also sidesteps the painful binary of the commercial and the academic, which has become ossified and almost unworkable. More on this soon!

“The Joy of Cooking (for Gertrude Stein),” in The New Yorker

Anna Russell attends a London dinner party thrown by Francesca Wade, author of the new biography Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife. She alludes to the labor of love that was the life built between Stein and her partner Alice B. Toklas, those two icons of twentieth-century arts and letters: Toklas silent in the kitchen, Stein entertaining the milieu. I look forward to reading this one and writing a longer piece on their writing and cooking.

Romance, by Parapraxis x Psychosocial Foundation

Parapraxis and the Psychosocial Foundation are running a seminar on romance from a psychoanalytic perspective with a great syllabus and list of speakers. Starts 7 September. I would sign up but it’s an awkward time slot in Asia, late Sunday nights into early Monday mornings. I really enjoy the way they introduce the question: “What is bad can feel good, and what is good can seem beyond one’s capacity to reach or realize. On the other hand, desire will not reliably bend to will or fiat. Given all this, can we engage in romance strategically? Or is the power of romance precisely that it undoes all strategy? Can we form attachments that do not provide momentary pleasure at the cost of planetary pain?”

“A Little Piece of Heaven,” in La Briffe

Ruth Reichl writes one of my favorite newsletters on Substack, in one amazing column revisiting the “Old Menus” she has archived from various stages of her career in eating and writing. I was really excited to read about her week at La Gonette, a retreat in the French countryside for creative people led by novelists Michael Cunningham and Alice Nelson. In Ruth’s description:

As far as I can tell novelist Alice Nelson and her husband, psychiatrist Danny Shub, thought about the world they wanted their infant son to grow up in. Then they set out to create it. They bought La Gonette, a 17th century chateau in the Luberon that belonged to King Charles’ favorite designer Robert Kime. Then they filled it with beautiful objects, mountains of books and an ever-changing cast of creative people. At La Gonette there is always someone in the kitchen conjuring up fragrant food, always someone on the terrace deep in conversation, always someone heading off to collect yet an even more interesting person from the station.

“The Remarkable Lives of Gwen and Augustus John,” in The Guardian

Jonathan Jones reviews Artists, Siblings, Visionaries, a new dual biography of Gwen John and her brother Augustus by Judith Mackrell. We have spent quite a bit of time with Gwen John via the books by Celia Paul and Rebecca Birrell; I know little about Augustus, who was the more celebrated in their time. Jones asks about what it means to succeed or fail under these circumstances, when the shifting grounds of aesthetic experience might completely invert over the course of a century. He frames Gwen’s creative ideal beautifully: “to be at liberty even if that meant existing in deepest solitude.”

Until next week—hope your road is a long one.