Experiments in the Studio

Do Ho Suh and Li Yuan-Chia make sacred spaces for little moments

Editor’s Note: Studio Experiments

Editor’s Note is a regular column introducing issues, themes, and frameworks from a personal perspective.

Looking at Bruce Nauman last week I was thinking a lot about the space of the studio as a site of experimentation, a lab for testing out ideas both material and conceptual that is understood to be accepting of failure and forgiving of wasted time. Coincidentally a couple days later, Jeff Waldman wrote about his approach to experimentation: noncommittal, low-pressure, small-scale data collection about what works and what doesn’t. He suggests starting as soon as possible, and as cheaply as possible. And his biggest takeaway is something that I’ve said again and again about the biggest decisions we face: “The only way to learn if a thing is the right fit is to probably just do it.” Bruce Nauman’s early approach to wasting time in the studio—measuring out the space-time of being in a particular place—was a low-cost series of experiments that opened a door into what would become one of the most consequential artistic practices of the later twentieth century. A lot can come of a little experiment.

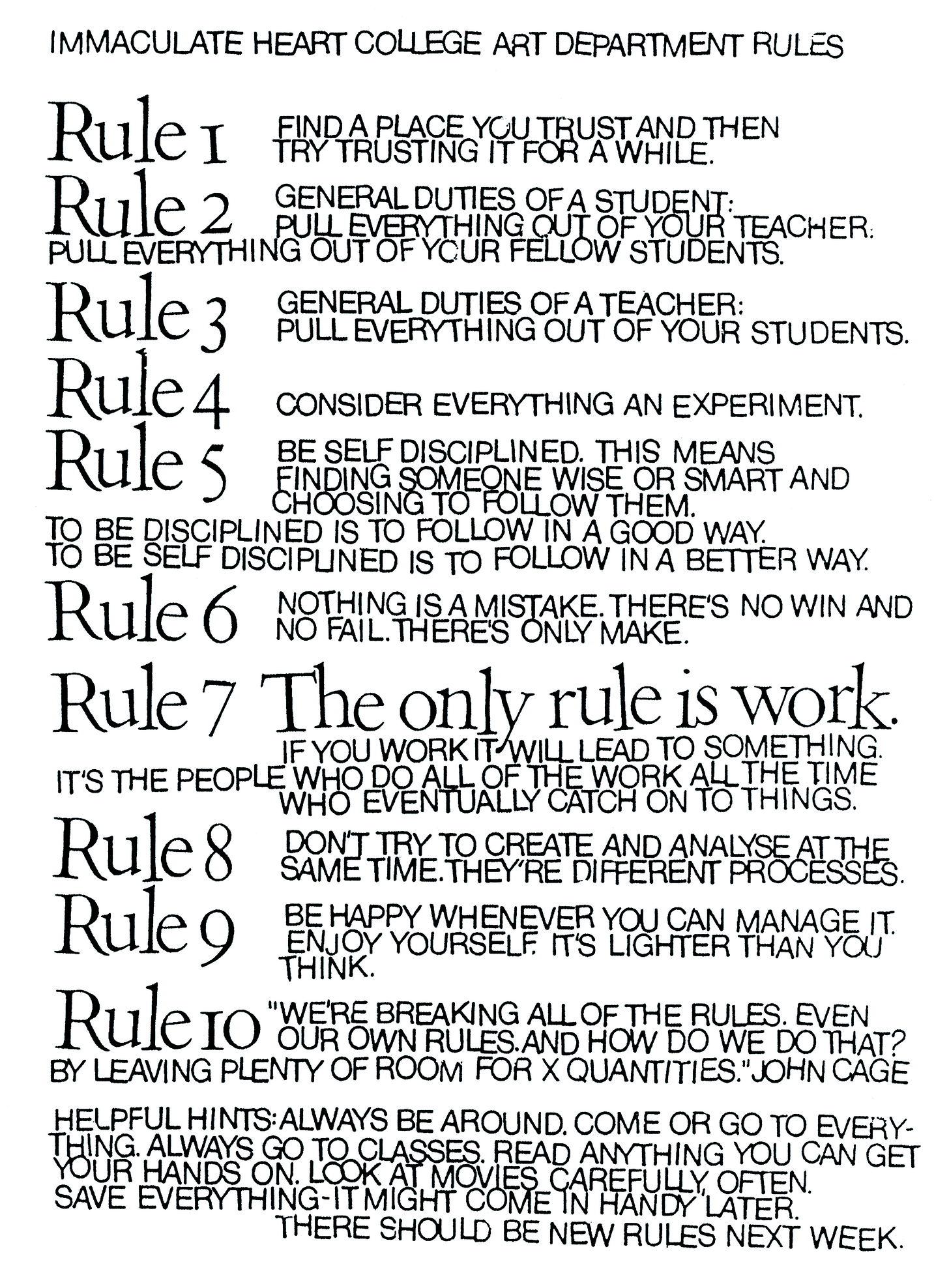

One of the things that we as non-artists need to learn from artists is how to structure the way we are in the world as a practice. Many artists do this intuitively, and bristle at the idea that there are principles in how they approach their next step. Others are clear and explicit. Sister Corita Kent listed rules for art: Consider everything an experiment. Nothing is a mistake. The only rule is work. I think there’s a great value in seeing the next thing we do as connected to the last thing we did, and pushing forward each next step as an evolution of our present moment. And of course, part of the freedom to this discipline is being okay with ripping up whatever we’re working on and turning to something else instead. Within a practice, any given experiment might result in a meaningful next step, but it also might push us closer to a meaningful dead end.

A lot of the artists I’ve spoken to for Lives of the Artists invite their children into the studio and let them have at it with whatever materials happen to be on hand, be that paints or scraps or a video camera. Part of what makes the experiment work is that there is no expectation of an outcome. There will be nothing to hang up on the fridge afterwards, nothing to hand in to a teacher. Instead you get mess: mess on paper, mess on the floor, mess on hands. When non-artists expose their kids to art education, they tend to want to see something come out of it, and they tend to want to like what comes out of it. When artists let their kids into the studio, nearly everything ends up in the trash. There’s no judgment. When there’s commentary, it tends to be in the process of the experiment, not on the result. What comes out of these kinds of experiments in the studio is something the kid carries forward with them—they’ve taken an invisible step that can inform how they approach the world around them. They can choose to take another step, and another.

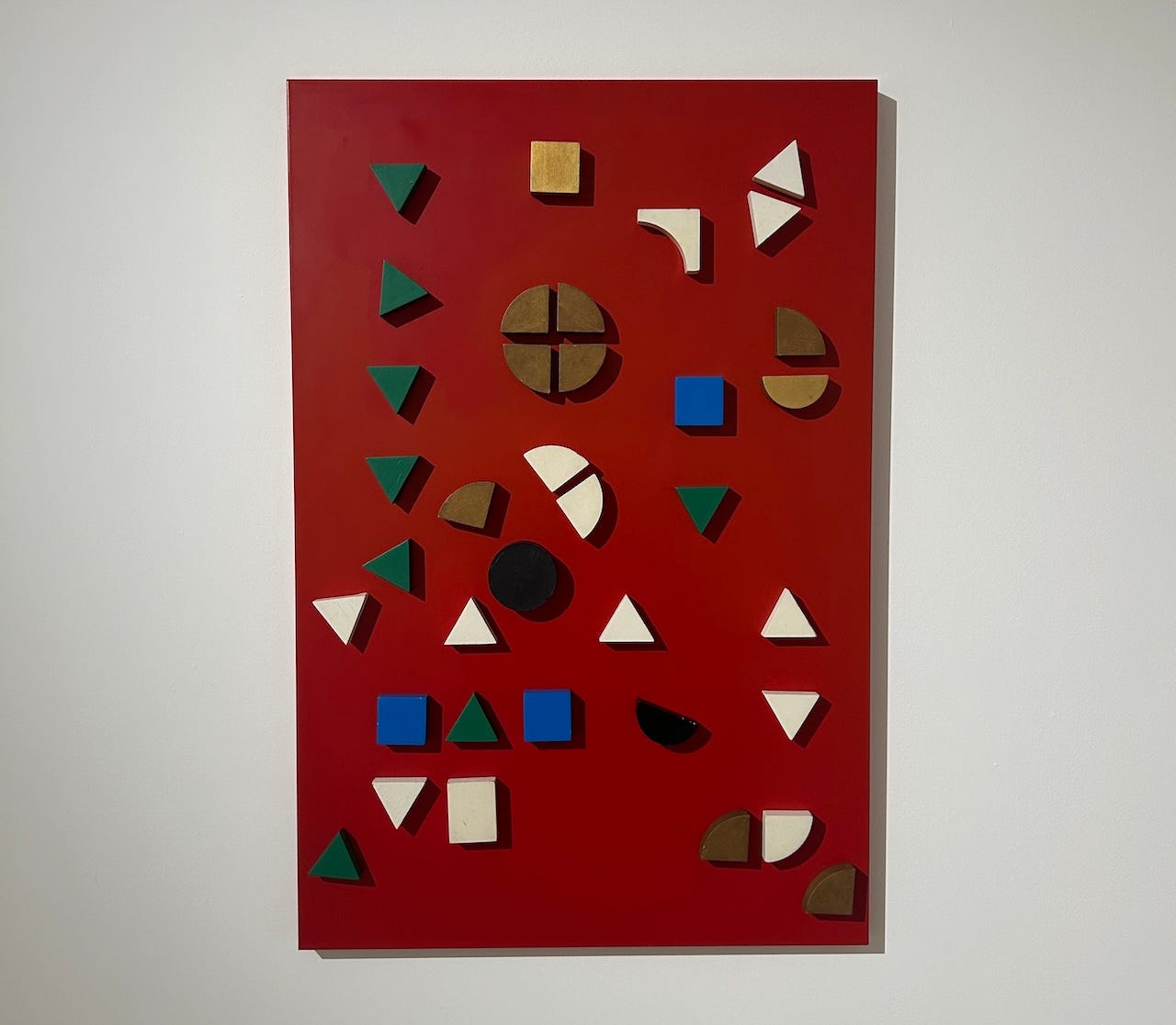

My daughter spent her weekend experimenting with a hot glue gun on the floor of her bedroom. While she was busy with that I visited two exhibitions, one of the late Li Yuan-Chia at Winsing Art Place, and another by Felix Treadwell at Dopeness.

Li Yuan-Chia was a colleague of Hsiao Chin, both pioneers of abstraction who came of age in Taiwan and then founded the cosmopolitan Punto group in Italy. He moved to the UK in the 1960s and fell in with the Signals group, eventually settling in Cumbria and opening the LYC Museum. This museum was partially a place for Li to exhibit the work of friends and peers and partially a community art space, welcoming contributions from neighbors and, importantly, children from the area. In this sense it preceded the participatory public art galleries that we see today. The exhibition in Taipei is strong, including work from my favorite series—wooden blocks attached by magnet to metal surfaces that can be reconfigured at will. Li was all about the spirit of the experiment.

Felix Treadwell is an emerging English artist who has a studio in Taipei where he paints a series of iconic characters that expand with psychic interiority: there are dinosaurs (many dinosaurs in this newest exhibition), an androgynized fashionable version of himself, and occasionally something like the xenomorph from Alien. For me Felix’s work is a reminder that what makes us who we are more than anything else is the terrain of the childhood we come from. In his new work I see him moving more into painting per se, letting the material guide the composition instead of working to an image. There are some clever color fields and blending practices on view, and it is evident that the studio remains a site of experimentation for him, too.

Read Jeff Waldman’s piece on experimentation here:

Icon: Do Ho Suh

Icon is a regular column pairing canonical works of art and quotations from pioneering figures in the history of art and life.

We bring our memories with us when we move and my memories inhabit the architectural pieces that I create, which are physical, but also psychological and metaphorical. What I bring is a skin, the thin skin of the bigger physical thing.

Do Ho Suh’s exhibition “Walk the House” is on at the Tate Modern for another month, closing on 26 October. I write a lot about concepts of home here, so it should be clear why Do Ho Suh has become such a touchstone for me. His most iconic work involves recreating spaces in which he has lived in fabric with traditional sewing techniques, so that they are sculptural and soft and monumental and translucent and present all at once. One of the centerpieces of this exhibition is Nest/s (2024), which sews together various liminal apartments and studios in which he has resided over the course of his life, each one its own striking color. What results is a monument to the places he has been and the versions of himself that he was when he lived in them, and a tunnel that allows us to walk through the space-time of his life as a young man, an artist, a father.

Do Ho’s first engagement with home was with his childhood ur-home, which he rubbed, inverted, and reconstructed for Rubbing/Loving Project: Seoul Home (2013-2022). You can feel the tenderness with which he approached this dwelling as an object, every detail of every corner preserved in its own slowly sagging mirror dimensions. Since then he has become interested in concepts of home more generally, often working with communities and documenting the architecture—as it is lived as well as how it is designed—in social housing and other sites of psychological significance.

Today I shared this quote because I wanted to point out this gentle pair of Time Pockets (2021). Do Ho sees architecture and clothing as intimately related, skins or envelopes that come between the body and the world and mediate states of thinking and feeling as much as they modulate our physical perceptions. I want to share his explanation of the project in full:

My wife and I decided early on that we would try and keep hold of as many of the little objects used by our children when they were young that we could. Our daughters were constantly growing out of their clothes and toys, and making the decision of what to keep and what to throw always felt impossible. We couldn’t come up with a system and decided to keep everything until our kids could decide for themselves. This is a huge privilege and a storage problem, but I’m so glad we did it!

I think the objects we touch the most accumulate our energies – which is partly where the idea of the fabric specimen (doorknobs, switches, sockets etc.) comes from. Because I always think about the interplay of clothing and architecture – the question of what is the space that houses us – we decided to try using clothing as a vessel for memories of the children’s early years. We made two smocks and asked the girls to pick the objects that were most meaningful and held the most memories for them. They were then placed in the pockets, like a three-dimensional photo album, only so much more tactile and physical than a photo album. The choosing process was the best part really!

Do Ho Suh also has a touring project for children called Artland, which has been through the Buk-Seoul Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and Singapore’s ArtScience Museum. Kids and other visitors get air-drying foam clay with which they can sculpt flora and fauna to add to big jungly environments. The results are cute and I’m sure it’s a fun way to get kids doing something hands-on in the museum, but if I’m being honest I’d rather just be one of Do Ho’s daughters sewing my most treasured possessions into the pockets of a phantom dress.

Until soon, enjoy the long way home.