For Children, For Beginners

Art for play and art as play, at the Haus der Kunst in Munich and at home

Field Trip: For Children in Munich

Field Trip is a regular column reporting on exhibitions and institutions.

I’ve written about the wave of exhibitions looking at design for children, art for children, and playgrounds by artists that we’ve seen over the past couple years. At the Haus der Kunst in Munich, “For Children. Art stories since 1968” is one of the largest and most comprehensive of these surveys, bringing together installations intended for young audiences as well as a certain level of historical and conceptual discourse around what these choices mean for the artist and for the museums.

There are two things I really like about this show. One is it speaks to a broader age range than most. When we imagine “art for children,” too often we immediately jump to older toddlers and lower primary years kids—the age set who can spend the afternoon doodling on the walls and floors, as they are indeed invited to do in Ei Arakawa-Nash’s Mega Please Draw Freely (2025), which occupies the central hall at the entrance to the exhibition. The Haus der Kunst also invites the participation of older youth and younger adults. They are given opportunities to participate in the work itself, like with Koo Jeong A’s HAUS DER MAGNET (2025), an indoor-outdoor skate park, and crucially, in the making of the exhibition, via a youth council that came together in advance of this show. As the proud father of a tween student council representative, I can confirm that there is nothing more important than making kids this age feel included in the machineries and bureaucracies that shape their lives.

The second thing about this show for me is it doesn’t shy away from the more discursive side of contemporary art—for every LEGO play tray and costume dress-up station there is a video installation or audio work. It’s able to accomplish this by stating clearly up front that “The exhibition is not a playground.” I like the effort to normalize exhibition-going as a practice for children, young people, and families: here is a hammock, check the sign, looks like it’s okay to lie down here, here is a guitar on the carpet, check the sign, not supposed to touch this one. As a result we find complex and layered relationships between reality and performance, from environments that welcome interaction to videos and documentation of moments from which we are excluded.

The title of the exhibition seems obvious and declarative: art for children. But it is an allusion to a Bruce Nauman installation that one encounters in the exhibition, a work in which we hear the artist repeat the phrase “for children” on a loop, which was itself titled after the Bela Bartok piano pieces For Children, originally intended to teach piano to young people. Bruce’s work was originally a part of “For Children/ For Beginners,” the latter half of which was a large-scale projection of “all the combinations of the thumb and fingers,” mirroring the poses of schoolyard hand games with the fingering positions of the piano.

This continues with work that I do not believe was made for children, but engages with the concept of childhood discursively, and in doing so makes itself legible to younger audiences. Antoine Catala’s Jardin synthétique à l’isolement (2014) is like this, using pictograms that were originally developed to communicate with non-verbal children. Harun Farocki’s Bedtime Stories films (1973-7) use his daughters as actors to explore the potential of the imagination of the child. In Lake Valley (2016) Rachel Rose draws on antique children’s picture books and classic animation. The result is stunning; I think Rachel is one of our top contemporary poets of both childhood and parenthood.

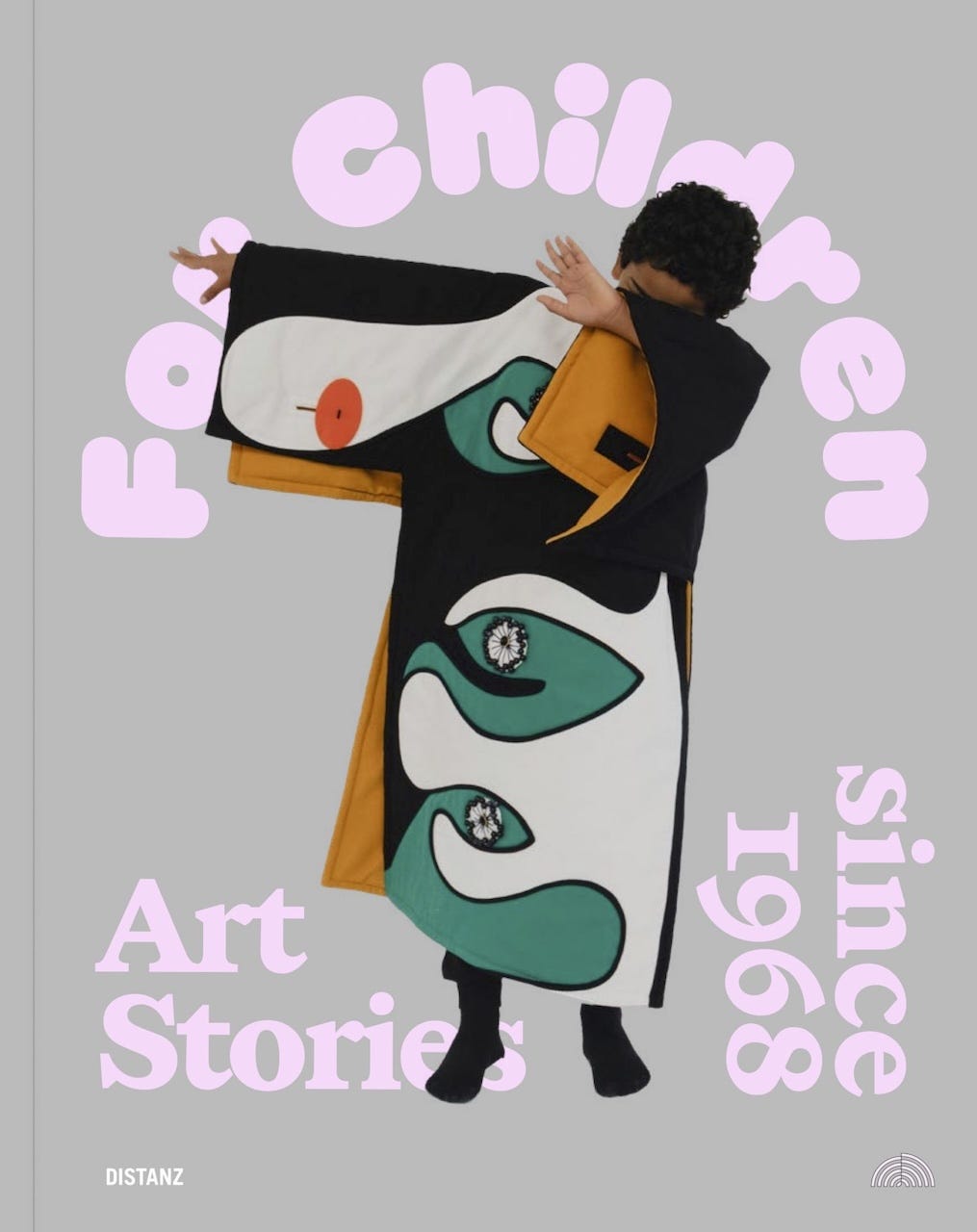

Another category of work draws on forms that will look fun and playful for children, often inviting interaction that feeds back into future iterations of the projects. Many of these were developed through the education departments or child-friendly commissions of other institutions. Basim Magdy’s How I Learned to Laugh at Failure (2018) is a set of altered ping pong, pinball, and pool tables with custom rules developed by children playing the game over time. Olafur Eliasson’s LEGO-based Cubic Structural Evolution Project (2004) we have looked at previously. Yto Barrada also used building blocks in Lyautey Unit Blocks (Play) (2010), with an optional dose of historical-political content. Rivane Neuenschwander’s The Name of Fear (2015-25) begins in workshops with children who share their deepest fears and then design capes to defend against them; Rivane and her collaborators then produce the capes as beautiful fashion objects that can be worn during certain designated times. The catalogue of the exhibition uses this image on the cover. Very much looking forward to reading this one.

Editor’s Note: Art and Play, Art as Play

Editor’s Note is a regular column introducing issues, themes, and frameworks from a personal perspective.

What I love about the projects in exhibitions like “For Children” is that while they are often interactive, participatory, and even fun, they are not always didactic. Children’s museums, whether they are the more traditional sort focused on science, technology, and society or the newer sort with educational projects by contemporary artists, almost always have a theme or a point to convey. Contemporary art as we think of it doesn’t have to be “about” anything at all—when we end up reflecting, it’s because we’ve gotten there through play.

Bruce Nauman is particularly important here. In many contexts art is told that it must be about something, that it must have a point. Bruce, with all the white male privilege of the late 1960s, asserted the moral right of the artist for art to be about nothing at all. The body in the studio: bouncing in a corner or walking around a square.

My proposal is this: What if we had an institution that showed projects like the ones in “For Children” consistently, all the time, as the heart of a program? What if they weren’t packaged as being explicitly “For Children,” but rather presented without comment to an audience that was presumed to include children as well as adults? What if there was art that you could touch and become a part of, but it wasn’t drowning in didactics?

I am so bored of thinking about art in the same binary categories: art that’s meant to appreciate in value for the market versus art that’s meant to signal the virtues of its community. The most exciting artists working now for me keep themselves far, far away from these orthodoxies. They believe in beauty and purpose all at once. Art is meant to play.

Play is one way that artists can create a space of freedom for themselves. Some playful art invites us to play along with it. This is the art that I find myself wanting to spend my time with right now. A little bit dangerous, a little bit pointless, and always very much open to the outside.

Learnings: Petra Cortright

Learnings is a regular column that digests some of the lessons from the Lives of the Artists.

Since my conversation with Petra I’ve been thinking about how different we all are as people, as parents, and as children, and how our preferences and inclinations define what we think of as good art, good parenting, and ultimately a good life. Petra and her husband Marc have completely different approaches to making art: he needs to bounce ideas around, take feedback, and work through it in relationship, while she wants to put her headphones on, close the door, and make her work completely on her own. Yet, somehow, their partnership works, and their expectations of each other are understood and respected. Petra also spoke about her approach to travel and self-promotion, on how she doesn’t like to bring the kids along to things. I decided early on that I was going to bring my daughter to everything that would have her, and institutions were actually remarkable accepting of that, often offering plane tickets and sometimes childcare to make the trips work. I’m glad that my daughter got the early exposure to art and culture and different parts of the world, but now as a middle schooler she’s completely lost interest and doesn’t even want to think about all the art fairs and biennials she’s seen, so maybe there’s something to the waiting strategy that Petra has opted for. Jin Meyerson also preferred a bit more distance between his second daughter and the studio life. Clearly there isn’t a right or wrong approach here. So many things work, and so many things also cause their own problems. One thing that I really loved about Petra’s approach was her inclusion of her own mother in their family dynamic. I think everyone who has access to help from grandparents has a great leg up. The conversation with Petra is here:

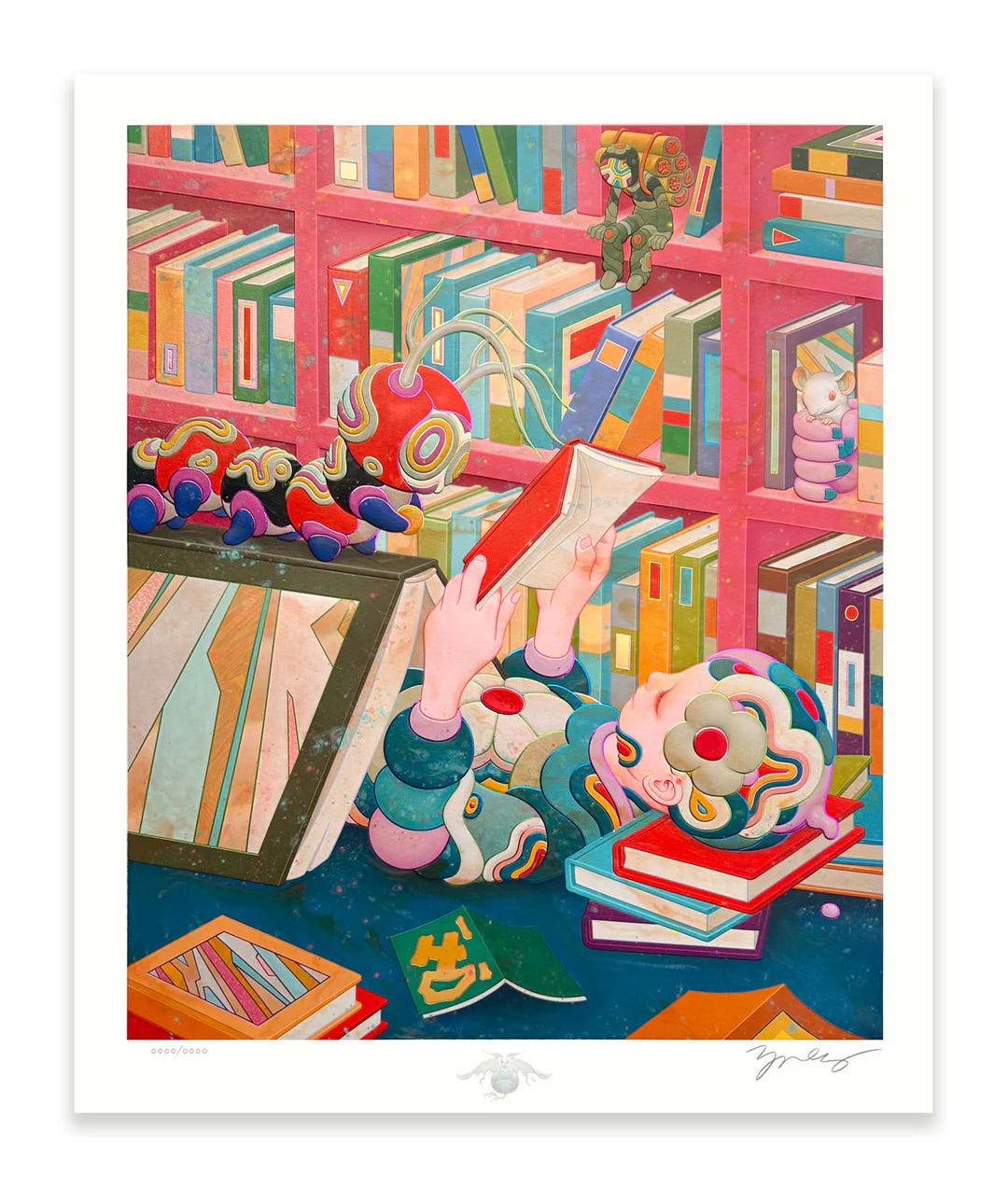

I wrote this week’s newsletter listening to Tito Puente, whose son sells a line of hot sauces along with El Rey del Timbal merch. I’m very excited that Lives of the Artists will be back towards the end of the month with a new interview with James Jean, the LA-based painter and father who is known far beyond the art world for the posters he’s drawn for many of your favorite movies. James has a new print that’s available today for 24 hours only that happens to be based on his son’s reading habits. Buy an edition here. Until next week, take the long way home.