Hockney’s Double Portrait as a Picture of Living and Loving

Janus the god with two faces, or the beast with two backs?

Looking at an artist’s social graph through the people portrayed in his or her portraiture, we can think in terms of the dimensions indicated by the number of people seen in a single composition. In the case of the self-portrait, we bear witness to the work of making seen what can only be felt. When we’re looking at a singular portrait of an intimate person, the artist’s lover or mother or son, we get into what I have called, after Brancusi, the zero-distance of the kiss: the possibility/impossibility of seeing a person with whom one is wildly in love, or else loves unconditionally. I mean this literally. Think of how the boundaries of the other are blurred in states of ecstatic intimacy, how one must pull back occasionally in order to allow the face to resolve itself again. When we see a cluster of intricate relations, as in Lucien Freud’s Large Interior, W11 (After Watteau), with a former lover, her son, his daughter by another former lover, and his then-lover, we are asked to think through the relation between the individual and the collective. This is an extreme example, but it stands in for the genre well: What is she doing there? What is he thinking? Does he see them differently? Can we see them at all?

But today I want to look at how one artist in particular handles the third degree of social portraiture: the double portrait, the picturing of a couple, the attempt to triangulate the zero-distance of the kiss from an external (if entangled) point and imagine how one lover sees another.

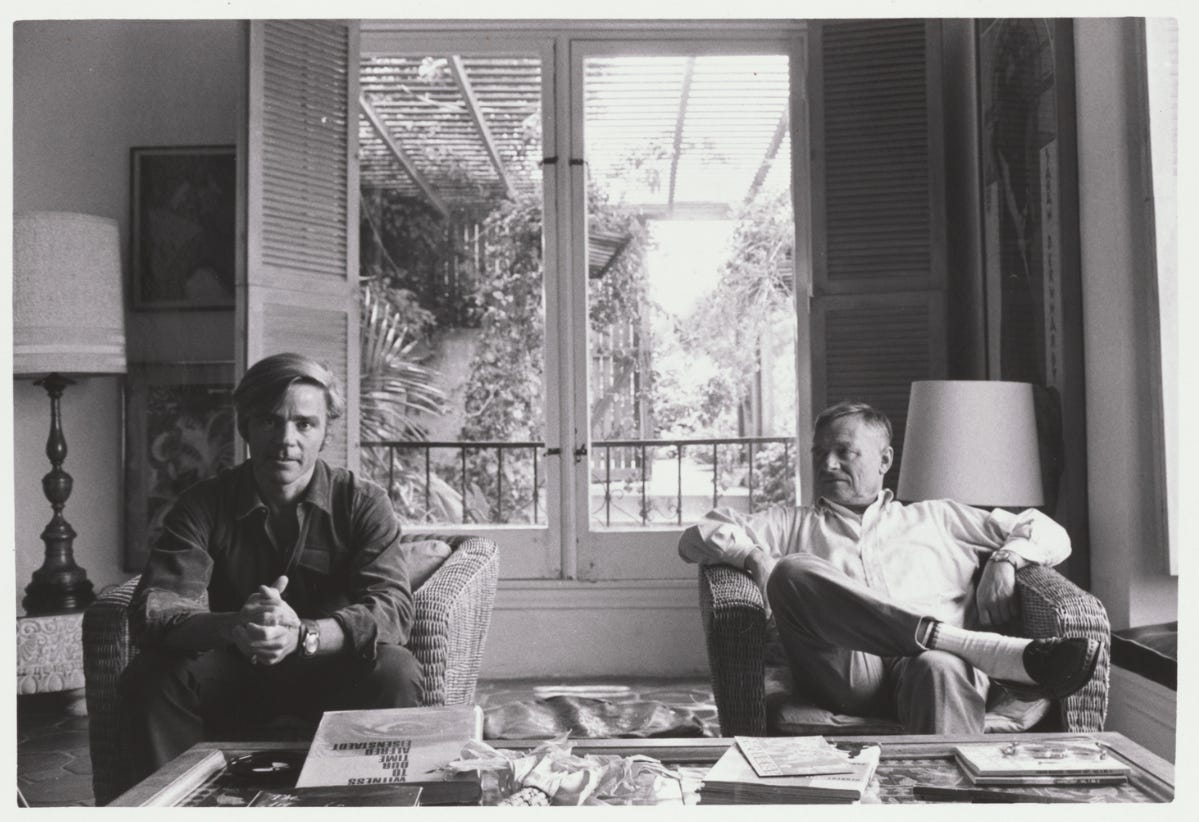

I am speaking of course of David Hockney, whose Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy (1968) was sold by Christie’s for USD 38m on Monday. This was the first in a series of double portraits that Hockney would execute over the course of a decade, and one of only two set in Los Angeles, despite the Californian breeze that we often assume to sense in so much of his work. Specifically, this one is set in the titular couple’s home on Adelaide Drive in Santa Monica, where Don Bachardy continues to live today. He is now 91. Christopher Isherwood was 30 years his senior, and passed away in 1986. Their home, immortalized in the painting, is remembered as a meeting point for several generations of Californian intellectuals, from those who fled Europe alongside Chris in the late 1930s and early 1940s to the Hollywood milieu who would become the subjects of Don’s portraiture practice over the ensuing decades.

Don looks straight ahead. Chris crosses his legs, head turned to face Don. David has written that this is the pose they assumed whenever he asked them to relax. They seem so firmly anchored in their armchairs, in perfect parallel, a balanced universe of two. While they face different directions, their bodies are much more at ease with each other, much more evenly treated than most of the couples we will encounter.

Hockney was 30 when he painted this double portrait, and looks shockingly childlike in photographs from the 1960s. Don would have been just a couple years older, Chris—one of Hockney’s points of entry to the LA scene—three decades beyond that. When David arrived in LA for the first time Chris would have just published A Single Man, the best-known of his American novels, beloved for its picture of a quotidian picture of an intellectual romance. He was, of course, already known for Goodbye to Berlin, the source material for Cabaret and one of the defining novels of Weimar Germany. Don drew or painted a wide network of friends and sitters, and recently had a retrospective, “A Life in Portraits,” at the Huntington. It closed in August.

One of the most heartrending things I have seen is Don’s book Last Drawings of Christopher Isherwood. It is utterly overwhelming. As Chris lay dying of cancer, Don captured him on a daily basis in black acrylics on large sheets of watercolor paper, ending the series only after he died. They had spent 33 years together, from Valentine’s Day of 1953 to January 4, 1986. They shared a life and a death, and the home they made continues to be Don’s. So what we see in David’s double portrait is a place, a time, a love, but also three creative practices balanced against one another, each relying on the other two in subtle ways.

Katherine Bucknell has edited a volume of correspondence between Chris and Don, published as The Animals. The title refers to their pet names for another: Chris was Dobbin, a “stubborn workhouse,” and Don was Kitty, a “playful feline.” Katherine has further adapted the letters for audio, in parallel with an audio adaptation of the play A Meeting by the River, which Chris and Don themselves adapted together from Chris’s last novel. I love this nested work of adaptation. It reveals how creative practices, when set alongside one another with an eye towards openness and connectivity, can make space for another as well as allow space for further hybrid forms.

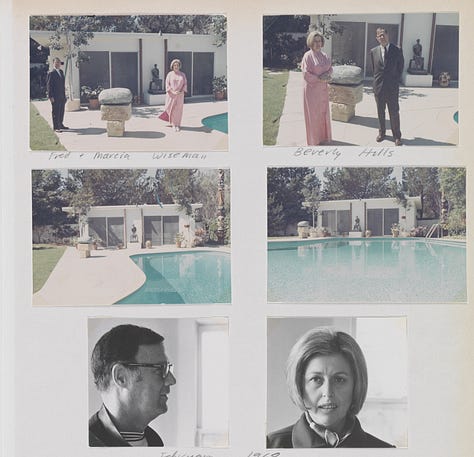

David’s second double portrait was American Collectors (Fred and Marcia Weisman), also completed in 1968 and also set in LA, in the sculpture garden of the visibly modernist home of the titular couple. Fred and Marcia were incredibly important to the foundation of the LA art scene, hosting in their home a series of important lectures that introduced modern art to a circle of people who would become major collectors and patrons. After their divorce, in 1979, Marcia donated her half of their collection to the nascent MoCA and became a founding trustee. Her brother was Norton Simon, who built up the Hunt’s Foods empire and endowed an LA museum of his own. Fred, who made his money through car dealerships after working for Hunt’s, set up a foundation for part of his collection in his home in Holmby Hills (the neighborhood between Beverly Hills and Bel-Air), though I am unsure if the home that now houses the foundation is the same home where David painted him and Marcia.

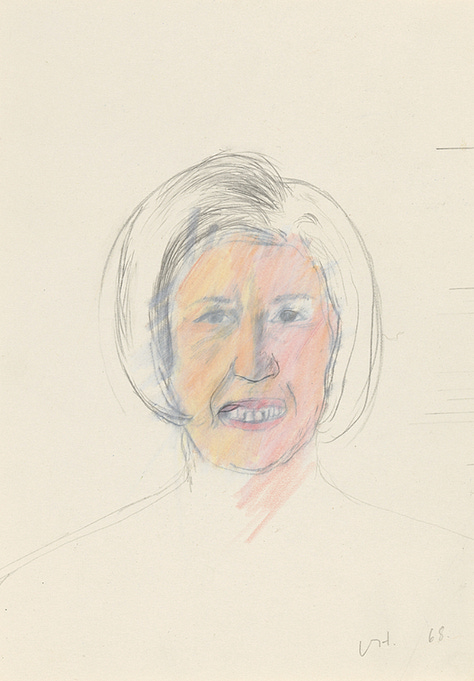

Marcia appears as the matriarch, facing forward in a bright pink dress that pops off of the seafoam greens of the poolhouse. Her face is almost grotesque. Looking at David’s photographs and sketches you can see what he did: a shadow from her bangs falls across her right lip, and he has integrated this lighting effect directly into the flesh of her cheek. He has used one set of photographs for the overall composition, and another set of close-ups for the faces. Fred faces towards Marcia but seems not to see her, gazing off into the distance. He is stiffly suited. His fist is clenched.

It is often remarked that, in comparison with other couples in the series, the Weismans appear rather flat, or even that David seems to prefer the Henry Moore and the William Turnbull and the totem pole to Fred and Marcia themselves. Apparently Marcia originally asked David to paint Fred, but he turned down the commission and offered to paint them as a couple instead. He worked from photographs. The couple did not particularly like the outcome, and sold the painting. If Chris and Don is a portrait of a relationship, American Collectors is a portrait of a marriage. It is now in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

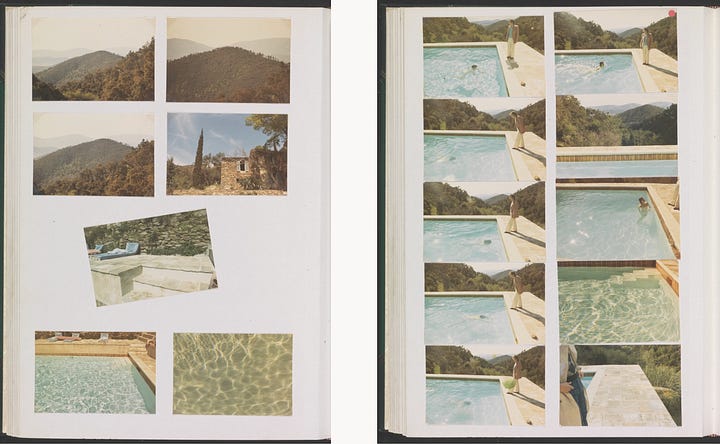

Those two paintings were done before the summer of 1968, when David returned to Europe and spent the summer with his lover, Peter Schlesinger, who then began studying at Slade. (Don studied at Slade in 1961.) During their summer trip they visited Tony Richardson’s home near Saint-Tropez, and photographed the infamous swimming pool that will soon be making a star turn in our tour of the double portraits. But first we stop in on New York. In December, 1968, and into early 1969, David was working on Henry Geldzahler and Christopher Scott.

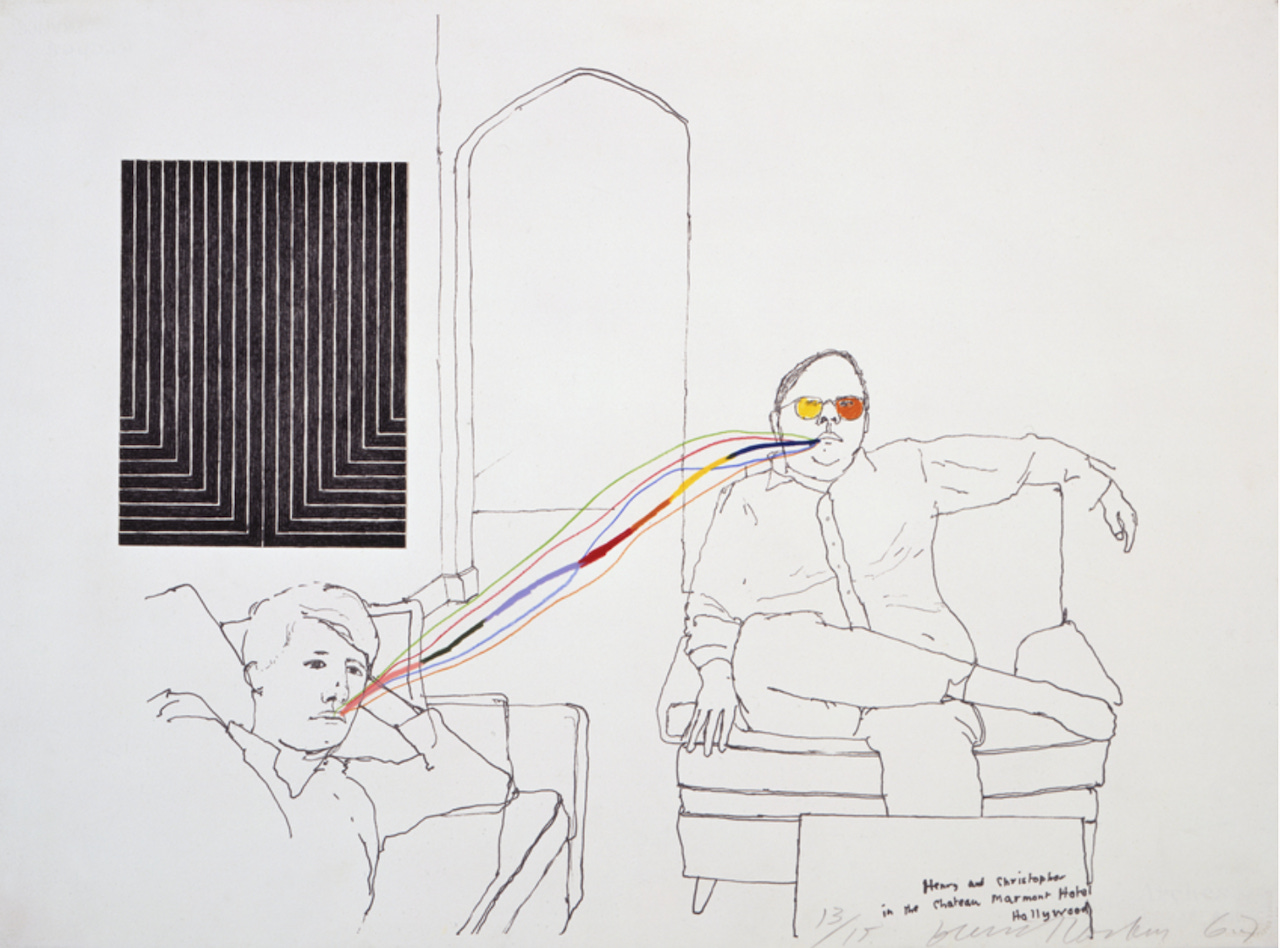

Actually, his first double portrait of Henry and Christopher was technically a lithograph he made in 1967. Scrawled in the corner: “Henry and Christopher in the Chateau Marmont Hotel, Hollywood.” Some of David’s sketches and prints are wonderfully weird. Henry and Christopher are connected at the mouth by an umbilical rainbow, a Frank Stella pasted into the space behind them.

Henry Geldzahler was one of the key curators of the era, first at the Met (where his “New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940-1970” would become a pivotal exhibition just a couple years later) and then later, after the painting, as the culture commissioner of New York City. There is a Warhol film of Geldzahler smoking a cigar over the course of more than an hour. Henry and David met through Andy. Like Chris (Isherwood), Henry left Europe for the States on the eve of World War II. Henry and Christopher is set in Henry’s apartment on seventh avenue.

Christopher Scott is described in most literature about the painting as a painter and model. Most of the scholarship on this painting focuses on David’s friendship with Henry. I don’t think that’s very fair, but I can’t find much about Christopher. He may still have his coat on, but this is still a double portrait. David apparently drew him at least one more time, but an image is not forthcoming. There is a Christopher Scott who helped found the Ridiculous Theater Company with Charles Ludlam in New York in 1967. The same? Ridiculous Theater Company was “campy and outrageous,” and its Scott had a background “in the fine arts,” and was an “advisor and consultant to art and cultural agencies such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the New York City Commission of Cultural Affairs.” That’s Henry’s CV. I say the very same Chris. I couldn’t tell you why he has been elided from the discourse, but he appears in the raincoat again in a studio photo almost ten years later.

Back to the painting. Henry sits directly in the middle of a voluptuous pink couch, one leg crossed, eyes looking straight out towards the viewer. Christopher has just entered the room from the right. As with Fred, he is depicted in profile looking towards his partner without seeing him. He has not yet taken off his raincoat. There is shadowy evidence of reworked paint around his face, as if he is new to the apartment, new to the scene, new to the painting, potentially on his way back out at any moment. The picture last sold at Christie’s for USD 49.5m.

In the fall of 1969 David was best man at the wedding of Celia Birtwell and Ossie Clark in London, having spent the summer with much of the same cast of characters, including Henry and Peter, with another stop at the swimming pool of Le Nid du Duc as well as a visit to the town of Vichy. He spent much of 1970 working on Le Parc des Sources, Vichy, a double portrait based on photographs and sketches he made on their trip the year before. Around this time we begin to see evidence of David’s fascination with the optical device. The reflections in Henry’s glasses in Henry and Chris, which the painter compared to Van Eyck. In Le Parc it is a horticultural device: a formal garden planted so that two skew rows of trees create a forced perspective, giving an impression of depth that makes the lawn look larger than it actually is.

We see two figures from behind: Peter and Ossie, two halves of the two great double portraits to come. A third, empty chair has something of a conceptual remit. David describes its aim:

I wanted to set the three chairs up for the three of us … then I’d get up to paint the scene. That’s why the empty chair is there—the artist has had to get up to do the painting.

There is something in this logic that is highly description of the compositions of the double portraits overall. The artist has arrived in order to do the painting, but in arriving something in his sitters departs. That, perhaps, is the nature of portraiture.

Throughout 1970 and into the beginning of 1971, David was organizing his photographs and sketches to execute the next double portrait: Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy. That would be Mr. Clark (Ossie), Mrs. Clark (Celia Birtwell), and a white cat (who turned out to be named Blanche; Percy was another cat, not pictured, but David preferred Percy in the title). At this time Ossie Clark was the absolute star of the London fashion world, and Celia Birtwell was the textile designer whose material he designed for. It is another example of the shared artistic impulse, here set off by the series of wry jokes that David inserted into the painting. Their creative practices went hand in hand throughout the 1960s and early 1970s until their divorce in 1974 due to violence, drugs, and infidelity. They had two sons together.

The painting is set in the bedroom of their flat at Notting Hill Gate. Ossie is seated, sprawled lazily across a Cesca chair, looking towards the viewer at an angle. His bare feet are buried in a thick sheepskin rug. There is a cigarette in his hand. The cat sits on his lap, facing towards the window behind. On the other side of the window, Celia stands erect on the same rug, hands on her hips. Behind her on a wall hangs an etching from David’s take on “A Rake’s Progress” (the piece titled Meeting the Good People, to be precise), a wedding present within a wedding present. Celia remained one of David’s most constant portrait sitters for years to come. Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy is today in the collection of the Tate.

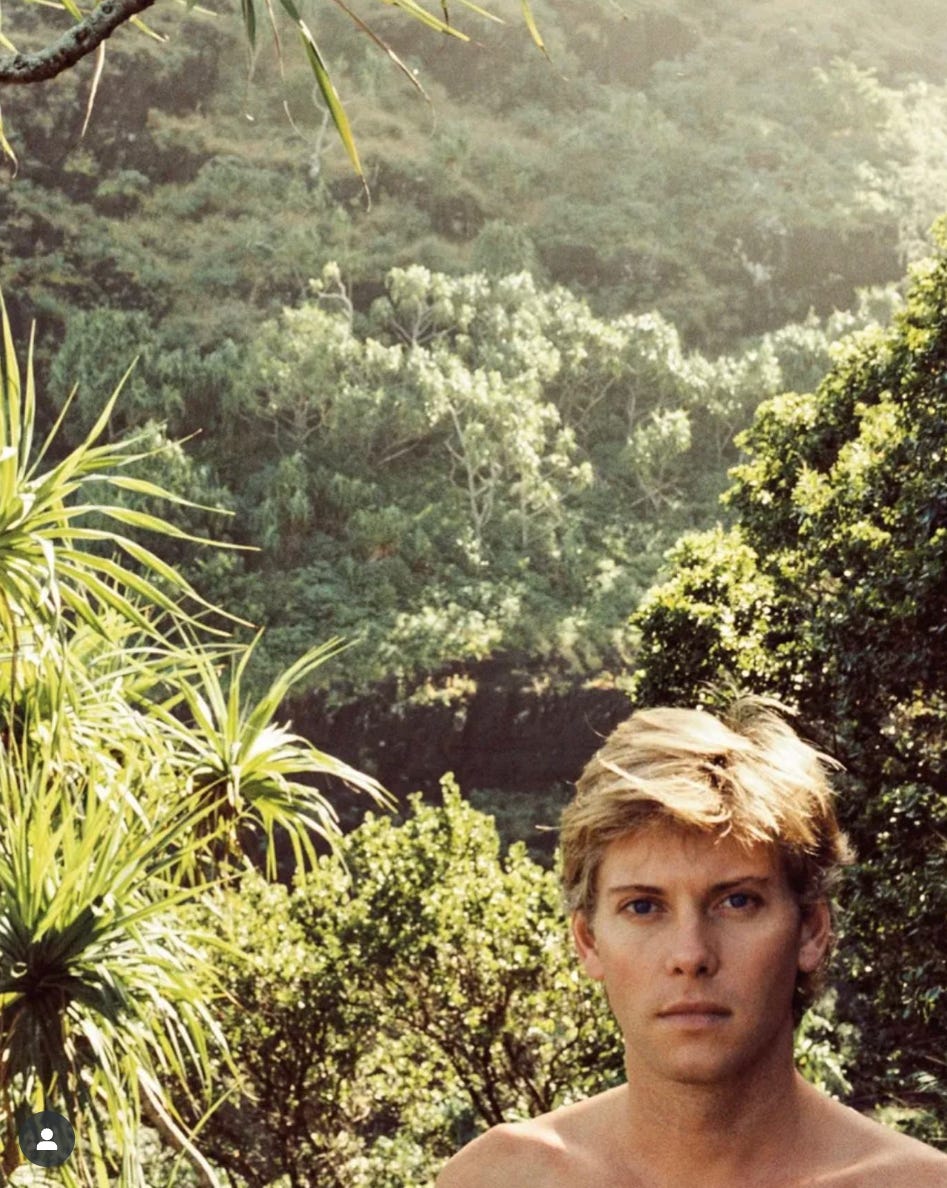

David Hockney and Peter Schlesinger broke up in Cadaqués in October, 1971, and in the year following the completion of Mr. and Mrs. there were no double portraits. There were a couple individual portraits, but mostly there were still lifes and empty studio corners. Many, many unpeopled paintings, many lonely paintings, including perhaps my favorite Hockney, the red pool ring floating alone in the vacuum. David and Peter met in the summer of 1966 at UCLA (David teaching, Peter studying), their relationship spanning the incredible period of productivity that we have covered so far, including the sublime 1967 high notes of A Lawn Being Sprinkled, A Bigger Splash, and Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool as well as the double portraits. There’s a great movie about these years. It’s also called A Bigger Splash.

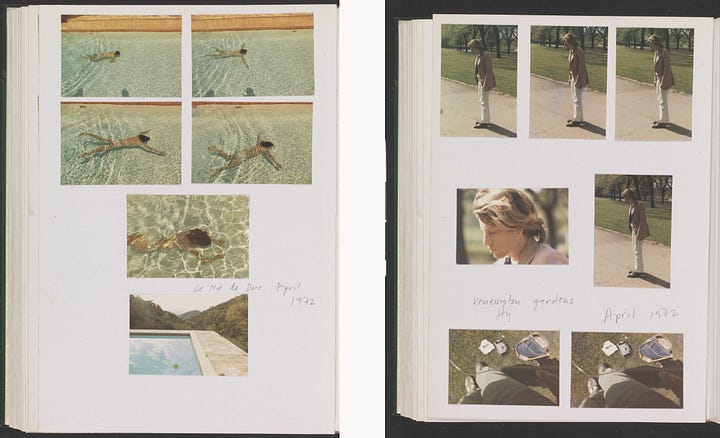

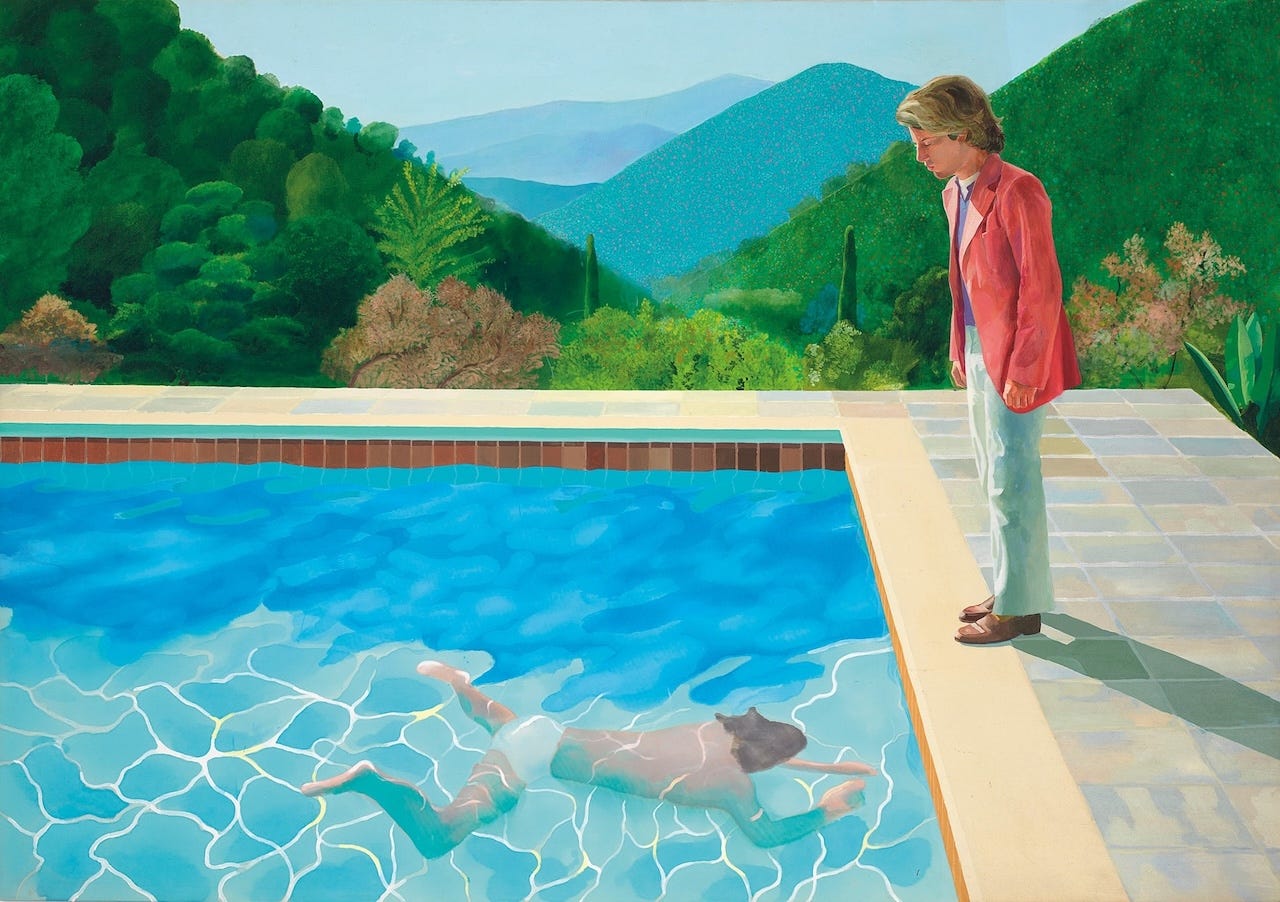

The next double portrait, of course, was Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), completed in 1972, which the market holds to be the best of the bunch. It sold for USD 90m in 2018 and now belongs to the Taiwanese collector Pierre Chen. David has said that he arrived at the composition by accident, when photographs of Peter and the pool ended up juxtaposed next to one another on his studio floor. In April of 1972 David flew back to France to see the pool at Le Nid du Duc again, photographed Peter some more, and then in May started the painting in earnest in London. It took a while, removing and replacing the background and ultimately repositioning the angle of the pool in relation to the picture plane. Although it’s the terrain of Saint-Tropez, one can’t help but see some of California in it. He is often quoted recounting all the sparkling blue pools he saw throughout the hills as he made his first approach into Los Angeles from the air.

In many ways it is an outlier among the double portraits. The light is totally different. The figures both face each another. But, weirdly, the one underwater isn’t anyone at all. That’s Peter standing at the edge of the pool on the right, fully dressed, looking towards someone underwater. But there’s no referent there. David has said the underwater figure represents some future lover (some have suggested, more specifically, Eric Boman). Peter posed for it in Kensington Gardens, so it was clearly an amicable breakup once they were out of the moment in Cadaqués.

Peter went on to develop a practice in photography and, later, ceramics, and built a home together with Eric, also a photographer, on Long Island. They met in early 1971 at Mr. Chow in London—by showing up early to a dinner party that David turned down—and spent 51 years together. A bit like Don Bachardy’s portraits, Peter’s photographs are the perfect social media record of an era that preceded the medium. The ceramics are cool too. By now it must be clear how much I dislike the imbalances that are often assigned to these paintings and the people in them. “Then-boyfriend,” “friend of the artist,” “muse.” I think they’re all very hurtful terms for people who clearly spent meaningful moments of time supporting one another, loving one another, amusing one another, and, yes, inspiring one another, too. To this day, Peter is remembered in a Portrait of an Artist, not a Portrait of a Muse or a Portrait of a Lover. It’s a portrait of two artists, really. Even three.

While Portrait of an Artist was completed in a haze of emotion, David was working on the next double portrait at the same time, George Lawson and Wayne Sleep, and found it equally frustrating. By 1973 he abandoned it and proceeded instead with Shirley Goldfarb + Gregory Masurovsky, which is perhaps even weirder than American Collectors. In the fall of that year he moved to Paris, and he became particularly interested in the architectural spaces he encountered there—see all of the balconies and windows he painted in those years, as if he took the center of Mr. and Mrs. and turned it into a whole genre investigation. In this case, Shirley and Gregory were American artists who moved to Paris in 1954, and David was struck by the arrangement of their tiny adjoining studio rooms: his, being on the inside, required him to walk through her space to exit. The window seat of studios. Again David focuses in on the little inequities of a relationship, and again it is reflected in the composition.

Both figures are seated, but they sit with a wall between them. Gregory sits on a bed with a drafting table in front of him, pen in hand, lit directly from above by a hanging lamp, facing outwards towards the viewer. On the other side of the wall, Shirley sits in a chair facing away from him, looking off to the right into the garden, her gaze echoed by a little Yorkie immediately in front of her. There is a painting, one of her own trademark mottled abstractions, on the wall directly behind. In order to show us this scene, composed as it is, David has replaced what should be a wall with a curtain, and then pushed the curtain all the way to the left, exposing a bare frame along the top and right edges of the rooms. Gregory is lit dramatically, while Shirley may as well be outdoors in California. They appear as if on a stage, actors in a play about to describe the portrait of their marriage. Shirley wears an incredible pair of heels, lacking only her oversized black sunglasses.

As a painter, Shirley had perhaps the bigger career—the light reached her sooner—but died young at the age of 55 in 1980, while Gregory survived until 2009. Her career tracked the transition from abstract expressionism to minimalism, as well as one from the school of New York to the school Paris (though Roberta Smith called her “not a very original artist”). He was a printmaker and typographer, and edited and published her journals after her death. Again, the shared creative practice, a product of two lives lived side by side, each one absorbing and reflecting aspects of the other.

David returned to George Lawson and Wayne Sleep in 1975 before abandoning it for good. Looking at the preparatory sketches and early photographs, he was clearly bothered by the handling of the large blank wall space, inserting and removing a pile of books and working over the surface repeatedly. During this phase his painting overall turns increasingly away from the naturalistic moment that encompassed the double portraits, and you can feel the energy for these kinds of large-scale social projects petering out. It looks like a dull painting at first, especially in comparison to the luminosity and theatrical eccentricity of the preceding pieces. But I think that blank space is a damn fine wall, dappled in a nasty London light.

George Lawson was an antiquarian book dealer and Wayne Sleep a star ballet dancer. It is set in George’s flat at Wigmore Place. This one only looks like an age-gap relationship—George was only six years older. He just dressed funny. But the composition remains unbalanced. George sits, of course, but here it is his gaze that avoids the viewer. Although positioned at center, he looks off to the left. Dressed formally in a suit, his right hand holds down a key on a clavichord. Wayne, by contrast, stands casually in the doorway, leaning against his elbow in tee shirt and bellbottoms, his eyes fixed on his older lover. In 2016, George described how he could still hear the G that he played during the sitting.

It was David who had introduced George and Wayne, giving him something of a special angle on the triangle of the picture, as with his role as best man to Ossie and Celia. George and Wayne dated in the early 1970s and maintained a lifelong friendship until George died a year ago. David donated the painting to the Tate in 2014, apparently finally deciding it was finished, and in 2015 George and Wayne did a goofy, charming photo shoot in front of the painting together, which makes me want to cry almost as badly as Don’s drawings of Chris on his death bed. I wish everyone in these portraits had the same chance. I will begrudge no one the opportunity to recreate Portrait of an Artist on the edge of a pool, and hope Celia gets to hold the cat next time.

There is copious scholarship on the double portraits as a body of work, and I can only summarize it in broad strokes here. As early as 1976 David himself agreed that in nearly all of them we find one figure rooted in space and another somehow passing through; we find them looking in different directions, creating a dynamic pattern of movement that passes from one figure to the other and then back to the viewer and the phantom of the artist. One compelling reading by Marco Livingstone sees in this dynamic a parallel with the Annunciation, which I find beautiful: the presence of the lover in one’s life as a kind of divine visitation. In their poses and architectural configurations, Marco reads “the sense of struggle between the impulse to connect with another human being and the need to remain separate.”

That would mark the end of the cycle of double portraits, more or less. Many of David’s circle continue to appear in his paintings, Henry and Celia most often, as well as others we have not yet had the opportunity to meet, like Gregory Evans.

But there is one final picture that both completes and breaks the series: My Parents. It occupies a special position because it is square, rejecting the logic of the room-like rectangular containers that have made space for all of these off-kilter bohemian relationships. And because David started the piece in 1975, including a self-portrait in a mirror positioned between his parents, then destroyed it and started fresh, leaving himself out for the final version in 1977. In the early stages he reflected:

It’s a very traditional thing to do, I know, painting one’s parents, but I think it could be a lot more than just that—their predicament, their lack of fulfillment, the desperate-not-knowing what they could have had out of life. And their relationship with me.

This painting, too, is in the Tate collections.

I will close with two pieces that do not belong to the double portraits as a series, but bookend this experience in time. The first is the only work by David to actually be titled Double Portrait. Dating to 2011, it is an iPad drawing of two pairs of scissors. Different colors, different sizes, still facing slightly away from one another.

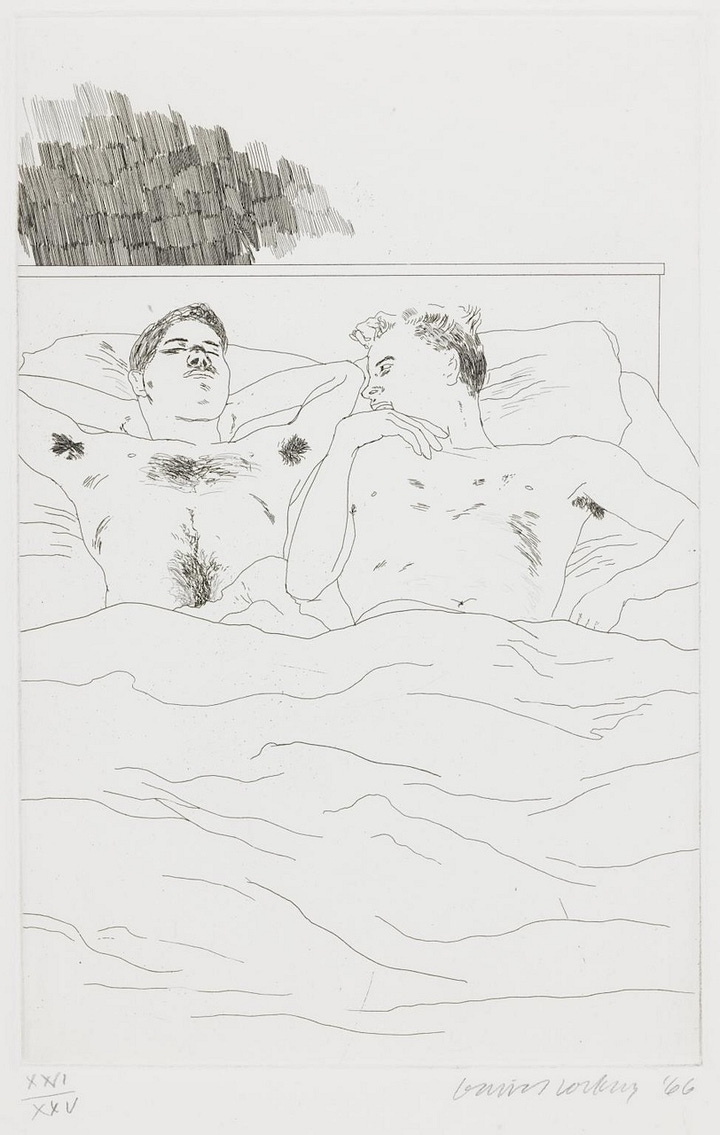

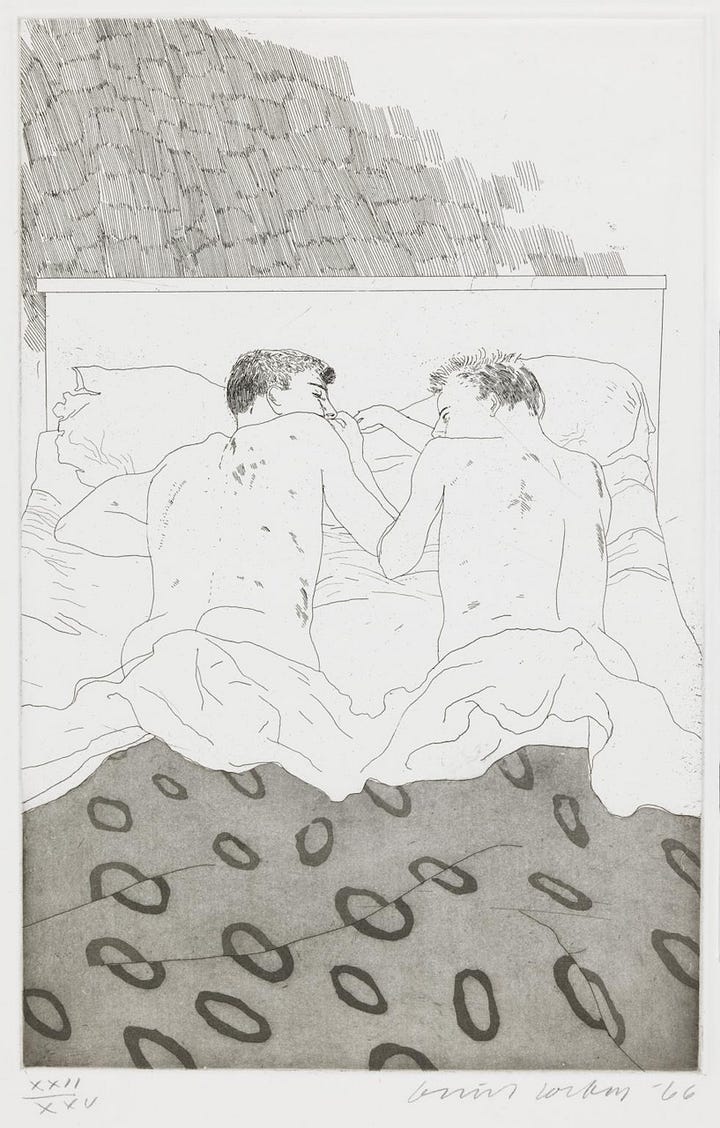

The second is In the Dull Village and Two Boys Aged 23 or 24, which I believe to be the first double portraits that David executed. They belong to a series of drawings known as “Illustrations for Thirteen Poems from C.P. Cavafy,” though in fact the published edition consists of twelve etchings for fourteen poems, edited and translated by the poet Nikos Stangos.

It is quite something to realize that David Hockney, too, is a Cavafy fan, although he appreciates the homoeroticism where I savor the yearning for a lost home. Nevertheless, looking at his position on the outside looking into these couples—functional or dysfunctional, lasting or already falling apart, balanced or tortured—I believe that these things are not so far apart. One of the poems in the illustrated edition reads:

When he went out in the evening (as it happened he had to get something to eat) to the coffee house where they often went together the squalid coffee house where they often went together— a knife in his heart.

The observation about one figure rooted in space and another passing through is brillant. It really captures the tension between connection and seperation that defines relationships. Your reading of Don Bachardy's deathbed drawings of Isherwood alongside the original 1968 portrait adds such emotional weight. The way Hockney uses architectural elements like the wall in Goldfarb and Masurovsky to literalize that emotional distance is striking.

Excellent essay! Another possible inclusion, or satellite, to the series of double portraits is his “Model with Unfinished Self-Portrait” from 1977. Gregory is asleep and Hockney, pictured within the picture, seems to be looking over him; very much like an annunciation or nativity scene.