Lives of the Artists: James Jean (Part I)

Is being an artist an excuse to shirk responsibility?

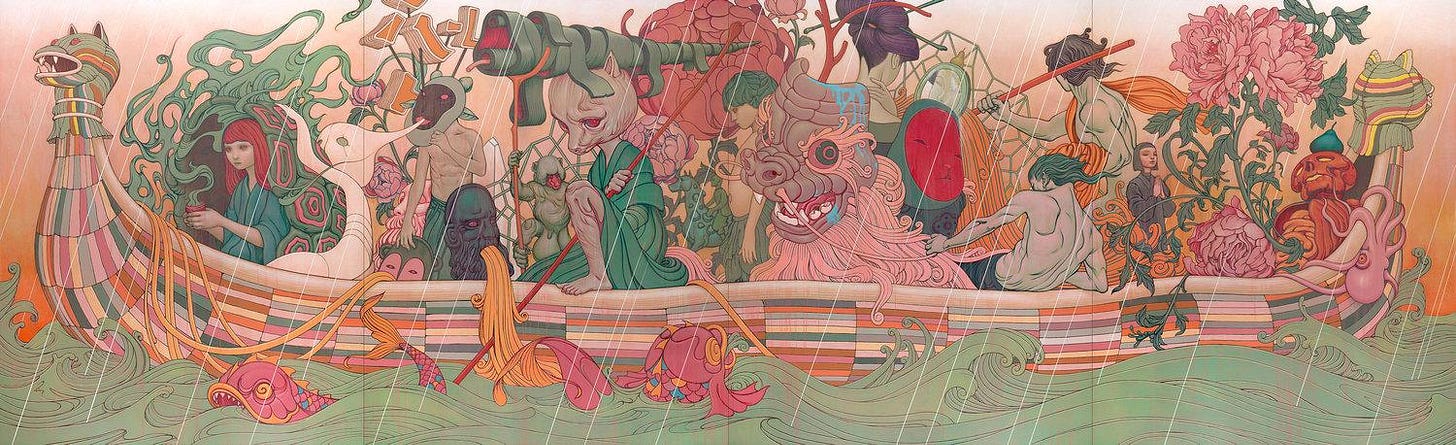

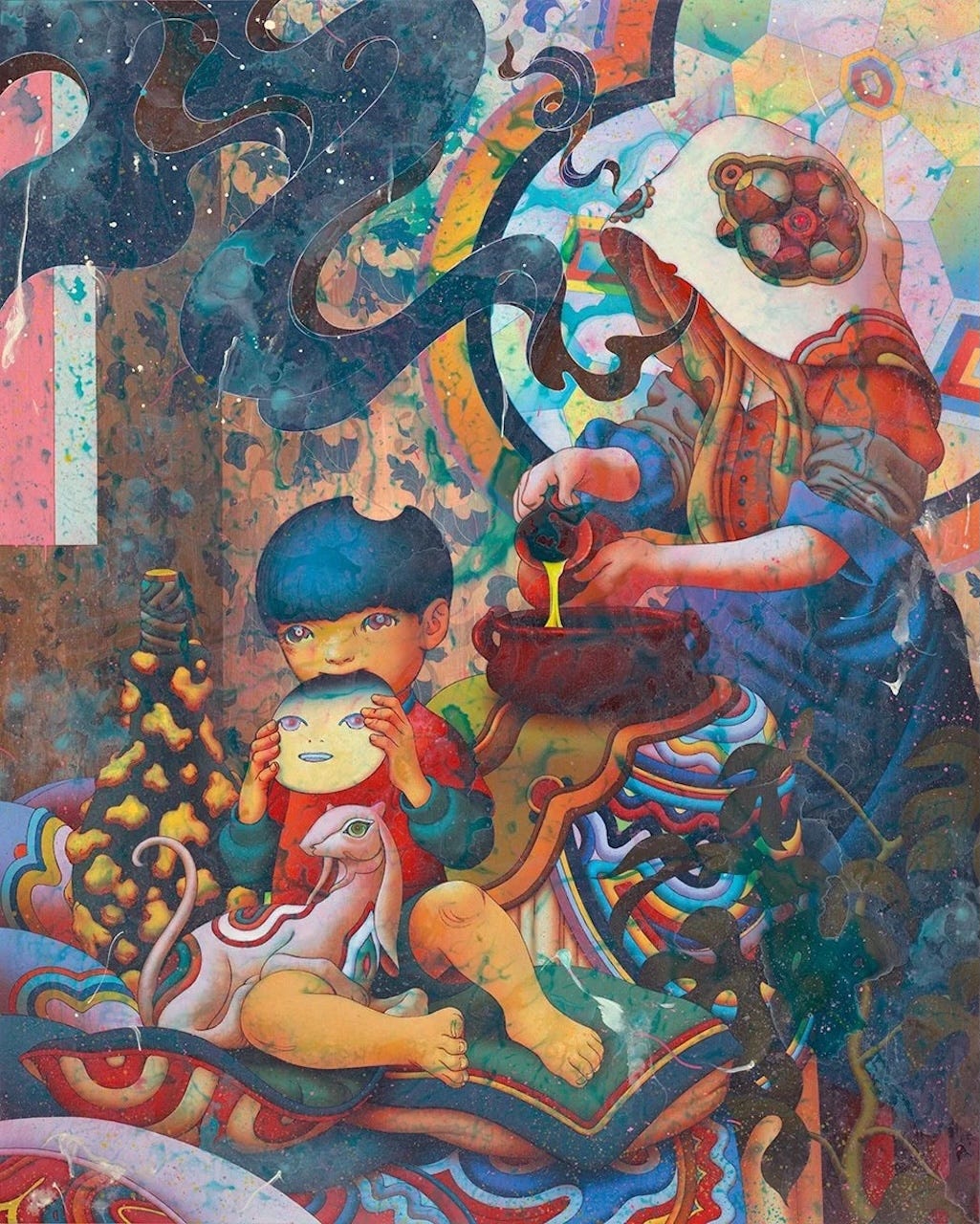

This month for Lives of the Artists I sat down with James Jean, the LA-based Taiwanese-American artist whose practice weds a contemporary rewriting of global mythologies with the kind of technical virtuosity that can only spring from an innate love of pencil on paper. So much of James’s work is about the magic that happens along the thin graphite line where form meets intention. We’ve worked together on a handful of projects over the past decade, from the “SFW” exhibition in Hong Kong in 2016 commissioned by Yvette Tang and Wing Shya to the “Eternal Spiral” mid-career survey that toured museums in Shanghai, Chengdu, Shenzhen, and Beijing since China reopened after the pandemic. In talking with James and looking closely at his work, I have learned a lot about how artists gather references, process and interpret everything around them, and then release themselves back into the world in different ways. Uniquely among the artists I’ve spoken with for LOTA so far, he’s less confined to the galleries-and-museums world and more open to following paths for creativity wherever they lead him: he’s had notable collaborations with brands like Prada, and has made the posters for many of the coolest movies you’ve seen lately.

In our conversation, James is candid about the sacrifices he makes to balance raising his son, advance his career, and push forward the work itself. As we will see, it can be tricky, and while the focus of mind and time that comes with being responsible for a young child can enhance productivity in one sense, it can also take away from work in other ways.

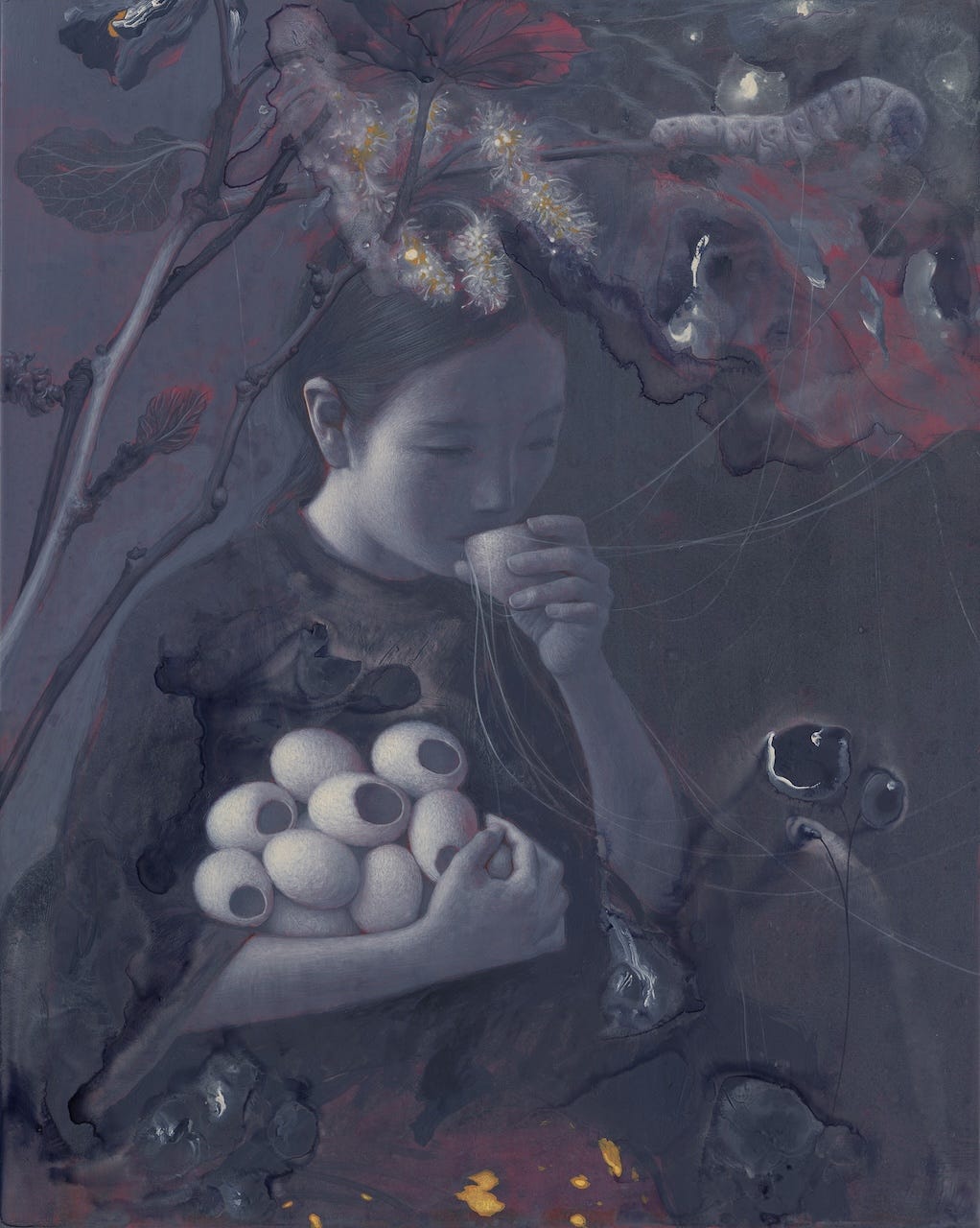

James has a new painting on the stand of BAIK ART at Art Jakarta, which opens this week. Don’t miss it if you’re in town for the fair. I’ve chosen to lead this issue with an image of that new painting, which is related to a myth about the invention of silk, and have selected a group of other paintings from the archive to accompany it. Next week, with Part II of our conversation, I’ll share James’s latest movie poster, as well as some older posters and drawings.

What was your childhood like? What was your relationship with your parents like, and what was your first exposure to art and culture? I’m curious about the first moment you felt like this was something you might pursue.

James Jean: I moved to New Jersey from Taiwan when I was three. My dad got a job working at Formosa Plastics, which is a pretty well known Taiwanese company making industrial plastics. The opportunity to move to the US was very prestigious back then, though the US has lost its luster these days. My mom taught high school English, and my dad still speaks with a very heavy Taiwanese accent. I grew up in the suburbs of New Jersey, riding my bike around the neighborhood—it was a very 80s, Stranger Things kind of upbringing. Both my parents worked and they wouldn’t get home until five or six, so I spent a lot of time off on my own and would have to get the rice cooker going every day for dinner. My dad also delivered newspapers, the Star Ledger, as a side hustle, and I joined him as well. When I was 13 years old, that’s when I first discovered comic books. All throughout my childhood I loved drawing, and I got a lot of praise for my drawing skills, but I never took it too seriously. I always loved to doodle. There was no outlet for it other than copying newspaper advertisements or photos of Batman and pictures I found interesting. My parents weren’t artistic at all, and I knew nothing about art history or the art world.

In middle school I got this issue of Wolverine from a classmate, I believe it was number 37, and my mind was completely blown, because that was the first concrete outlet I could see for drawing. I fell in love with comics and became obsessed, and helped my dad deliver newspapers early in the morning to earn money to go to the comic book store every Wednesday. That’s what we did throughout middle school and high school. My parents were happy I finally found a hobby or something I was passionate about, but they definitely did not see art as a viable career path. I was a pretty good student. I was in marching band, jazz band, pit orchestra, and even made it to All-State band every year. I took a lot of AP classes, but when it came time to apply to colleges, for whatever reason, I only focused on the School of Visual Arts and also the University of Arts in Philadelphia. Those were the only two schools in the area that had a cartooning program. I only had the equivalent of one semester of high school art, and then maybe another semester of portfolio prep, so my actual portfolio was very undeveloped when compared to kids who went to art high schools. Admission standards were low, and when I applied, the admissions office was pretty shocked that I was even considering art school, because they told me no one had ever applied with these test scores, since I got a 1540 on my SATs and had like a 4.3 GPA.

My parents were very disappointed. I remember my mom even cried when I told her. She was very worried. She’s sweet and sensitive, and my dad is more disciplined and entrepreneurial. He gave me The Art of the Deal when I was in high school, but I never read it. He was always ambitious. I feel like I inherited both sides, the more empathic and the more entrepreneurial. It’s a fortuitous combination. When I started art school I wanted to prove to them that I could be self-sufficient. I lived very cheaply. I got scholarships. I also worked a variety of different jobs to get myself through art school. My third year of art school coincided with the internet bubble in New York. I had a job at a children’s educational website on Wall Street. This was when everyone was making websites out of Flash and all these startups were having crazy parties and spending money like crazy. It was very extravagant and insane. And then the bubble burst in 2001, and the World Trade Center collapsed down the street from where I worked. I graduated with very few prospects. I sent my portfolio to various book publishers and got rejected. Almost as a last resort, a friend recommended me to an art director at DC Comics. I dropped off my portfolio, but what impressed him was my sketchbooks. That led to a seven-year gig doing covers for Vertigo comics.

Proving myself to be self-sufficient was at the forefront of my mind. By the time I was 25 or 26 I started doing pretty well as a commercial artist, as an illustrator, and then my parents could start bragging to their friends. And then I did a big collaboration with Prada in 2007, which was finally a name that the general public could recognize and appreciate, and I took time off from doing commercial work to focus on my own painting.

The one thing I always had trouble reconciling was always feeling disconnected from my ethnic background. Growing up, my parents would always speak to us in Mandarin, but then they would speak to each other in Taiwanese to have “adult” conversations. Because they had their conversations in Taiwanese, I was unable to absorb adult communication. Even now, my partner barely speaks English, and I’m isolated in my own world, and don’t share a language with her family. I’m recreating those walls that existed when I was a child, but somehow I’m okay with not being able to communicate fluently.

I remember being really struck the first time you told me about how much you enjoyed the feeling of being surrounded by family and having those connections without being able to actually communicate. In a way that’s a function of art. You can sublimate all of that feeling into a visual output. Artists often aren’t the best verbal communicators.

It’s a way to relinquish responsibility. My childhood was pretty lonely, so in a sense, I’m recreating that trauma. Artists like to be on the margins of society. I still feel like an outsider, even though my practice bleeds into the mainstream with commercial collaborations and social media. Despite my perceived success, I still feel like an outsider because I haven’t been able to enter the art world as thoroughly as some of the people I came up with. I see them navigating the art world in a much more agile way. I don’t know if I’m self-sabotaging, but it’s difficult for me to leave the family for work. I see other artists constantly traveling all over the world, away from their families and children, because they’re so singularly focused on their art. I can’t do that because I enjoy being close to family, or feel duty-bound to be around and making sure everything is taken care of.

Is it more enjoying it, or is it more duty and responsibility?

Maybe I’m a bit of a masochist. There’s definitely suffering there. It feels normal for me. I’d feel guilty if I were self-indulgent enough to travel for weeks away from the family. During Covid I remember seeing an artist do 30 days of quarantine in China because he had a museum show, with a new quarantine in each city. That’s impressive to go to those lengths. I admire the focus. I guess I feel inadequate in that way. Then you see someone like Virgil Abloh. He had a family, but he was so focused on his work, even to the detriment of his health. He didn’t take care of himself the way he should have, and passed away much too young. I’m not willing to go to those lengths. Yet. When my son is 18 or 19, on his own, maybe that’s when I’ll be able to go full tilt.

But there’s a distinction between being committed to your work as a practice and being committed to the promotion of your work, being out and doing the road show all the time. I get the feeling that you’re extremely committed to your work in a studio sense. Maybe, in a way, being around the family and having that home environment keeps you locked in and gives you a really stable way of working in the studio. What’s your studio setup? How far is the studio from home and how do you do it?

I think you’re right. Being close to the family does create a structure that I’m forced to adhere to. I used to work from home. My son was born in Japan, and then we moved to LA in 2015 and renovated the house and the studio. The studio has shifted formation a few times. At that time I had two assistants, and they worked with me for a long time. It was very structured. Eventually when my son was old enough for daycare there would be a certain amount of time available for me to work. Now that he’s in elementary school I’m able to drop him off and pick him up every day, so that sets the schedule. My assistants come in at 10, and they work until 6pm. These days I play table tennis from about 5:30 to 6:30 to get a bit of exercise. It’s become a de facto middle-aged men’s group that’s formed around this ping pong table.

There’s another middle-aged men’s group I’m in, which is the directors group. I go to Guillermo del Toro’s house on Sundays and we paint plastic resin model kits. Jon Favreau will be there, because he’s also in the neighborhood. And then there’ll be guest directors who come by, like JJ Abrams or Jason Reitman. Steven Spielberg’s been a couple of times, although I never met him. He took my spot! As you get older it’s important to have these third spaces. It’s our way of inoculating ourselves from the male loneliness pandemic.

My son does karate four or five times a week, plus Japanese school on Saturdays and tutoring. It’s all within walking distance. His elementary school is a five minute drive away. Everything is pretty tight and efficient, so I’m able to get a lot done within a certain amount of time. No wasted moments. When I was younger I was mostly by myself. I’d be in the studio staring at the canvas for hours and pacing around, wasting time. Some could argue that that’s important, to let things develop in your subconscious. But when I look back at that work, it’s not very focused. Now that I’m forced to work in this more compressed way it actually produces stronger work, and I’m more productive as well.

Over the summers we take our son to Japan to go to public school in Tokyo. In the US, I deal with all the school stuff, all the communications with teachers and counselors, all the stuff that’s usually handled by mothers. Then, in Japan, my partner takes care of all the educational and medical stuff. We split duties that way, hers for two months, mine most of the year. Her English isn’t completely fluent, so she doesn’t feel confident in catching all the nuances in the social situations at school, which can sometimes be delicate and difficult.

Obviously you’re very involved as a father. Is that something that was really important to you from the outset, that you wanted to structure your family life that way? Or has it evolved over time in response to how things have gone?

It evolved over time. Honestly, I didn’t give it much thought when she got pregnant. I face things as they come. But subconsciously I knew I’d be very involved as a father. Obviously there are a lot of unknowns, but if you try to predict the future, you end up causing a lot more suffering than is warranted. You want to make the best possible choices for your family. You want to optimize everything as much as possible. But it’s impossible to know what’s best. Choosing the right school, the right area, the right environment. When you have a baby, you want to protect them from all the evils of the world, but eventually you have to live in this poisoned world. You see your kids playing on Astroturf in the park. You know Astroturf is bad and full of toxins. But then you see how much fun that they’re having. You can’t prevent all the ills of the world from contaminating your pure, innocent child. They’ll be corrupted anyways. You can only ever do your best.

Check back next week when we get into the vulnerable heart of how home and studio life sit together, plus James Jean’s thoughts on the state of childhood today and what parents need to be paying more attention to. We talk through how artists’ styles change as their ways of working change at different stages of their lives, and look at the idea of breaking through a creative plateau.

Refreshingly candid, gentle, grounded.

Love James, his work (+ethic) is an engine for motivation.

I needed this. Im an Artist first time dad with a 9 month old son. I’m having success but also feeling more lonely than ever. Tired than ever trying to optimize everything. Trying to be a good dad, husband, artist, business person. I’m not worthy to be aside my hero’s but far along that my local peers don’t understand what it’s taken. I think that’s life. Dealing with life as it comes. Picking the lesser of two evils. But always moving forward.