One Mother after Another

Vuillard, Hélène Bessette, and Paul Thomas Anderson

Editor’s Note: Who I Am and Why We’re Here

Editor’s Note is a regular column introducing issues, themes, and frameworks from a personal perspective.

Lots of new readers have joined us over the last two weeks via the interview with James Jean—welcome and thank you James for sharing! Glad to connect with so many people who find his work and life as interesting as I do. I thought I’d take a moment to introduce who I am and what Nostos is all about.

My name is Robin and I am a divorced father to an 11-year-old daughter attending middle school in Taipei, where we live with a Formosan mountain dog named Brownie and a ragdoll cat named Karma. We moved here six years ago so I could take a job as director of Taipei Dangdai Art & Ideas, an art fair that attracted galleries from all over the world until earlier this year, when I resigned and the fair went on hiatus. My daughter was born in Beijing, and during our time there and later in Shanghai I was the editor-in-chief of LEAP, then the main bilingual art magazine in China. Her mother is the director of a museum in Jakarta, so since she was born I have thought a lot about what it means to grow up in a creative family: how we communicate our work with our children, how we encourage their creativity, and how we balance the logistics of careers that tend to have very fuzzy boundaries.

I have been working on this in fragments for around 10 years, and started Nostos early this year to dissect my experience as a single parent working in contemporary art, a field where artists and curators are encouraged more often than not to pretend that children and family do not exist. I looked around at many of my friends with children and saw the brilliant ways in which they approach this balancing act, and wanted to make public some of the conversations that might otherwise remain private. When my daughter was little, I indulged quite a bit of male privilege: when I showed up to professional settings as a dad with a kid in tow I was met with a degree of welcome and positivity that moms were not. This plays no small role in the co-parenting arrangement that we have chosen.

At the same time, we are living in a golden age of early years art education and accessibility to contemporary art and culture for children, especially in places like London, where multiple interactive experiences are available at low or no cost on any given weekend. Even here in Taiwan, the Taipei Fine Arts Museum has a basement exhibition space dedicated to rotating exhibitions for children, and the Taoyuan Children’s Art Center has a full building of its own.

So, Nostos exists to explore the relationship between art and life. The heart of the project is the column “Lives of the Artists,” in which once a month or so I interview an artist (or other creative parent—in the pipeline we have designers, chefs, architects, and others) and dig into how their personal lives and creative practices bleed into one another. Other regular columns include some of the ones you’ll find below today: “Icon,” which focuses on the private life of an art historical figure; “Book Report,” in which I read books touching on the creative life; “Projections,” about movies; and “Links” to other corners of the internet. Not featured this week are “Field Trip,” in which we visit exhibitions; “Learnings,” in which I reflect on and collate things artists tell me in conversation; “Homework,” in which these artists give my daughter and I creative assignments that you can follow along; and “Essays,” a more occasional series of longer writing that ties together some of the looser threads of the rest of it.

In addition to this weekly Substack, you can find us on Instagram (Nostos and Robin). Beyond the editorial content, other projects I’m working on include artist-design playgrounds and play structures to be installed at museums, and pop-up events for creative families. If you’re interested in what we’re doing, please subscribe and share to others who might want to join too, and if you have any ideas or would like to collaborate, drop me a line by replying to this email or leaving a comment.

Icon: Édouard Vuillard

Icon is a regular column pairing canonical works of art and quotations from pioneering figures in the history of art and life.

“My mother is my muse.”

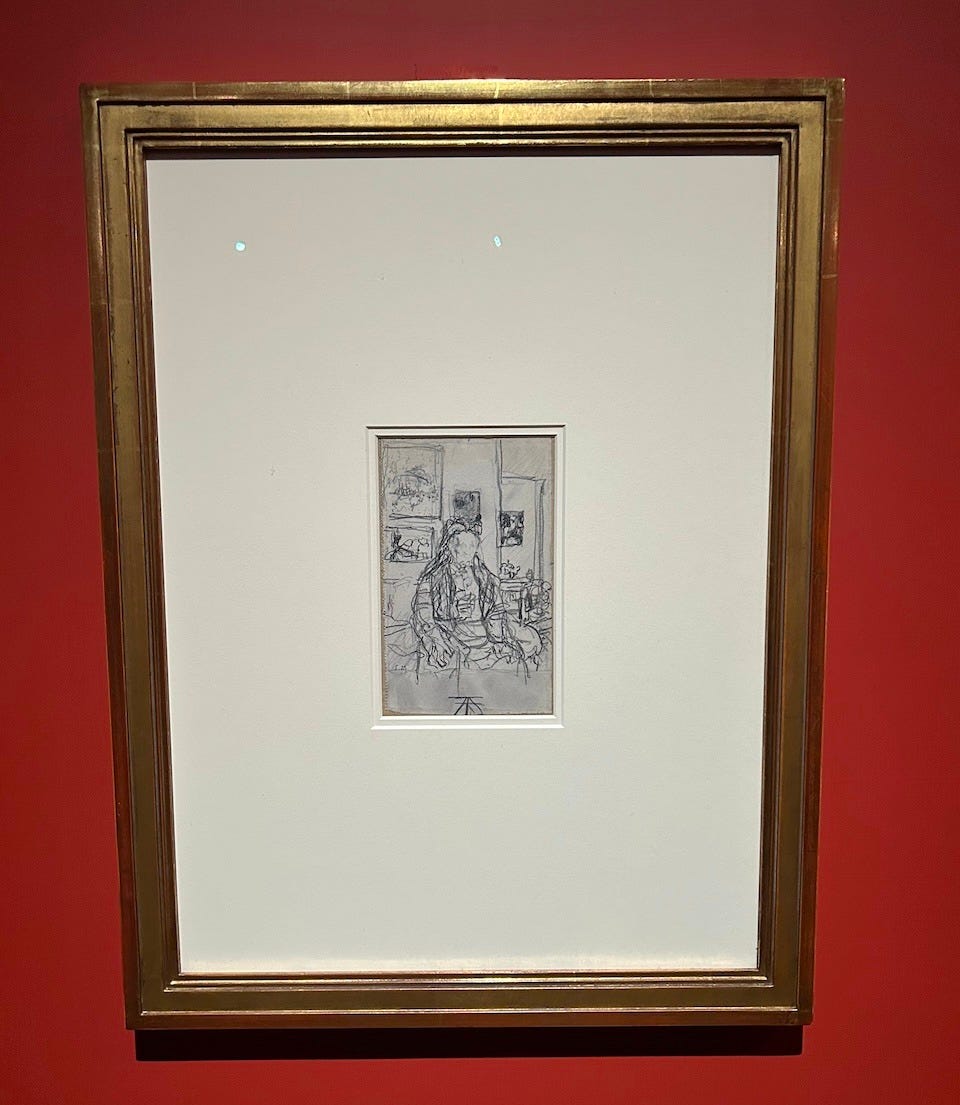

Last week, without really planning to, I had a date at a touring exhibition of the Met’s Robert Lehman collection at the Palace Museum in Taipei. It was so packed and the exhibition flow was so awkward that it was difficult to see anything at all but, fortunately, people tended to cluster around the larger, more colorful paintings, leaving occasional gaps around some of the smaller drawings and works on paper—one of the strengths of the Lehman collection. One of the few I was able to get a picture of was this delightful Vuillard drawing of his mother.

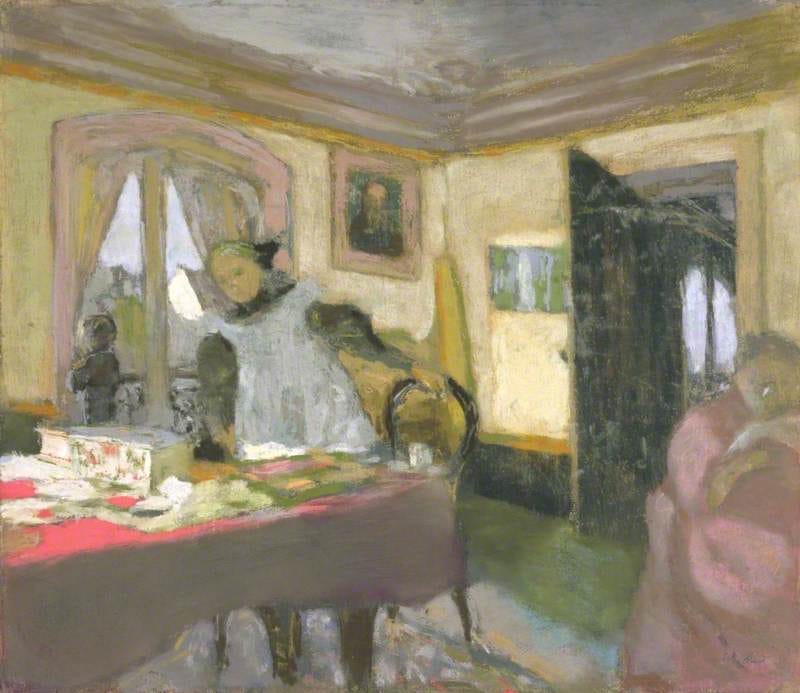

Les Nabis are feeling really hot right now. By whatever logic of rediscovery and reemergence our compulsions follow, I have been spending a lot of time looking at Bonnard, Vuillard, and Vallotton this year, particularly the interiors. I suppose it’s because of the thread that I followed earlier this year from Alice Neel back in time to Suzanne Valadon and her luscious upholstery, and from there into the other domestic painters of her era, learning from more gifted scholars and viewers of art how to read the social and political clues of interior arrangements.

Maurice Denis speaks for Les Nabis:

Remember that a picture, before being a battle horse, a female nude or some sort of anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.

Camille Mauclair says of the Intimists:

A revelation of the soul through the things painted, the magnetic suggestion of what lies behind them through the description of the outer appearance, the intimate meaning of the spectacles of life.

That the little Vuillard I snapped depicts his mother is natural: she appears in more than 500 paintings over the course of 40 years. He painted from a bedroom studio, and they lived together until she died. An unattributed text on the Moma website describes her as “the gravitational principle that prevents a collapse.”

There seems to be some really exciting research done on the gendered domestic lives of Les Nabis. In a previous issue we touched on Bonnard’s muse, his partner Marthe, who appears in endless configurations—often in the bath—throughout his oeuvre. With Vuillard the muse is the mother. I am desperately taken with how these different kinds of loving relationships might differently structure an artistic practice: what different modes of obsession, of attention, of tenderness, of care. While Vuillard never married, he had a 40-year affair with Lucy Hessel, the wife of his friend and dealer Jos.

Francesca Berry curated an exhibition for the Barber Institute of Fine Art titled “Maman: Vuillard and Madame Vuillard,” from which much of this biographical sketch is drawn, and has recently published a monograph titled Édouard Vuillard and the Nabis: Art and the Politics of Domesticity. I would love to read this for inclusion here but will have to wait until the paperback is out next summer rather than spend the USD 84 for the PDF e-book version that is currently available.

For a talk in Oregon, Francesca described the life they shared:

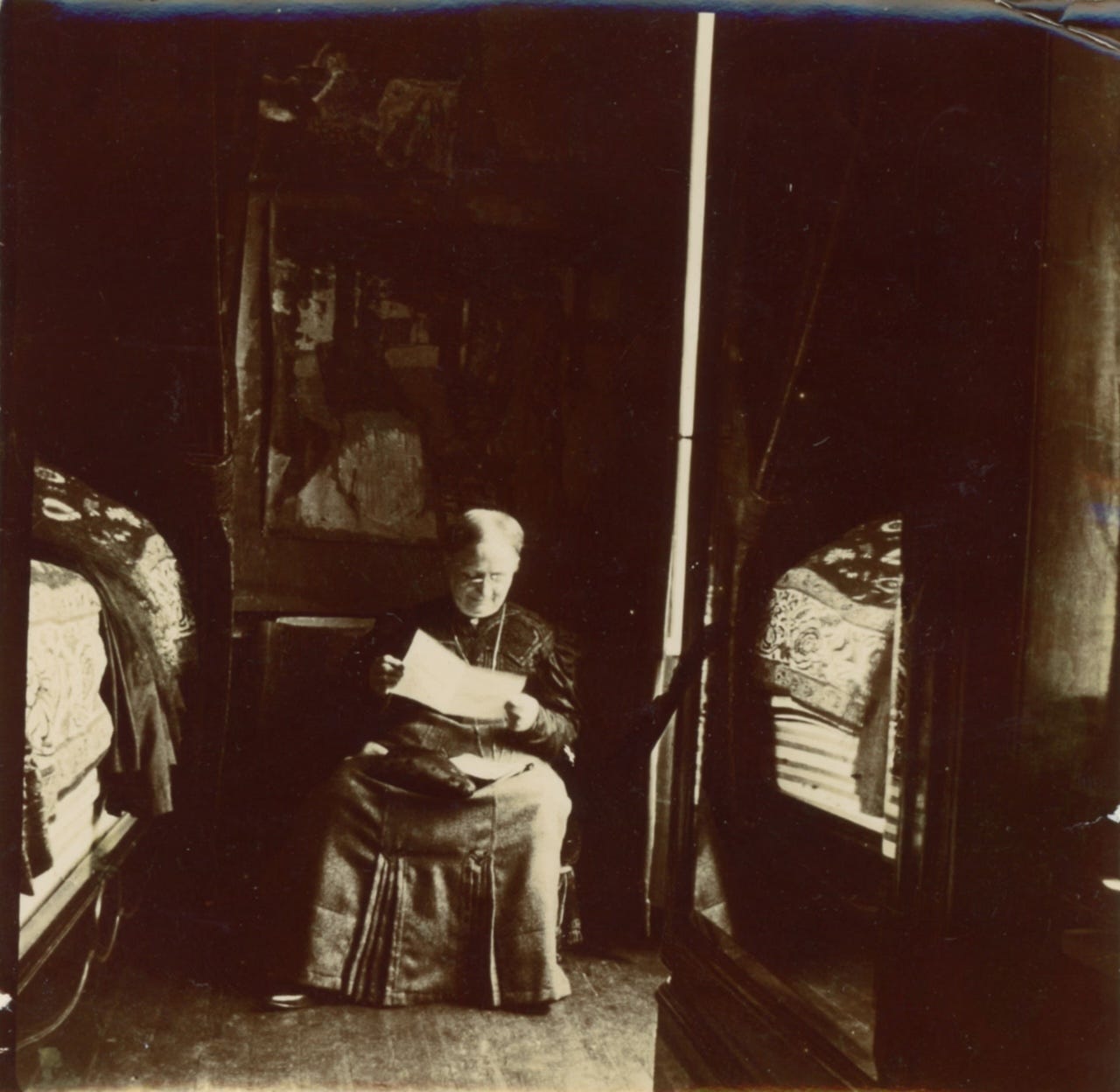

In these rooms Vuillard and Madame Vuillard operated mutually supportive, parallel working practices: Vuillard put his mother and her small sewing business ‘in the picture’, while she posed for his pencil and camera or printed his photographs.

I am fascinated by the family business angle to this, and love how these economic activities seemingly marginal to the practice of art actually end up being precisely what the art has been made up of all along.

Reviewing Francesca’s exhibition, Laura Cumming triangulates a complex relationship between the matriarch, her browbeaten daughter Marie, and Édouard the observer:

She is posing, but also pausing for a moment from her labours, her wistful face downturned. Madame is just through the door. Will Marie even be allowed to drink that coffee?

Marie married Édouard’s colleague and friend Ker-Xavier Roussel, and her children—Édouard’s niece and nephew—became some of his favorite subjects. They all lived together in an apparently claustrophobic series of apartments.

Francesca describes the structure of one complex composition featuring them all:

Madame Vuillard intently reading a large book … a contrast to the rising figure of her granddaughter Annette (b.1898), and the silhouette of her grandson Jacques (b.1901) hovering, perhaps melancholically, at the window. Félix Vallotton’s framed portrait of Vuillard, depicted at the compositional apex of the painting, enhances its tripartite intergenerational composition.

The painting is shaped by the practice is shaped by the life.

Book Report: Lili is Crying

Book Report is a regular column that reads books for, by, and about artist parents.

Speaking of codependent relationships between matriarchs and browbeaten daughters in early twentieth-century France, I recently read Lili is Crying, a short and lyrical novel written in experimental prose by Hélène Bessette first published in 1953 and recently translated for Fitzcarraldo by Kate Briggs. That name might seem familiar: Kate is the author of The Long Form. Her novel is all about fragmentation, particularly the kind that comes with having a newborn baby around. The brain is functioning differently, and it’s impossible to get anything done in long blocks of deep focus. You skim across the surface of the hour for days and nights on end, coming up for air whenever it is possible.

Lili is Crying asks what it would look like for a relationship as intimate as all that, a relationship between mother and daughter, to persist past the age of 20, 30, 40. There is an excellent introduction by Eimear McBride that helps translate some of what’s happening in the novel, because the language is hardly transparent, jumping between points of view, between dialogue and explication, but mostly between points in time, occasionally throwing out numbers to suggest that Lili is at this moment this age or that without any real sense of internal coherence. We know that we are in a small town in rural France, that Lili is the daughter of Charlotte, better known as “the mother,” that she has run away from home several times but has always ended up back with the mother, who runs a boarding house.

In one memorable episode, Lili says “I refuse to leave with the man I do love. Instead, I leave with the man I don’t love.” Perhaps she loves a bureaucrat in her 20s, elopes with a foreigner she doesn’t love in her 30s, and has an awkward affair with her younger cousin, the local shepherd, in her 40s. To spite her mother, to please her mother, to leave her mother, to come back to her mother. The mother, we suspect, is not only a person, even a particularly dominant one, even the sort of parent who can only create a sense of themselves in the choices of their children, but also an internalized way of being: the mother burden.

One of my favorite scenes involves a dinner at which the mother has made up her mind to host Lili and the husband she doesn’t love, only to be so offended by him that she offends him in turn and he resolves never to return. Over the course of the meal, his inner monologue turns toward his own mother, and to the meaning of a mother:

Children have to get on with their lives. Mothers stand at the threshold of the home, to watch their children leave. It’s destiny. Even so, children never forget their mothers (and mothers never forget their children).

But family meals can turn

on a screw

on a nail

on a word.

That reminded me of the saying, familiar to parents of teenagers, that the job of a child growing up is to kill their parents, and the job of the parent is to survive that metaphorical murder.

One line is repeated several times in several contexts, seemingly emerging from several of the men in Lili’s life:

“He knows what a mother is.”

Eimear’s introduction sets up the stakes of the book for Hélène as a writer: she was hailed as a rising literary star before it was ever published, but somehow her published acclaim never lived up to the promise. When she set to writing full time she was divorced with full custody of one of two children, who later became a literary collaborator of a sort. Kate Briggs writes that together they authored a manifesto for her work. I am ever besotted by a family manifesto. She was also known to incorporate character sketches from her social circle into the writing, beginning in Australia where she began her first novel before returning to Paris.

There is an excerpt from the novel here, which gives an excellent sense of the texture of the language. In my mind I picture Marie tending to her children and Madame Vuillard reading this very book at the table:

The novel is taking its leave

gently

like a fire going out

like a fire going out

like a fire going out.

Like a meandering stream losing its way.

Like a trickle of water parting.

Like a wind abating.

Like a sun dying.

Read my piece on Kate Briggs’s The Long Form here:

Projections: One Battle After Another

Projections is a regular column on films that touch on living in a creative family.

On another date last week—a week of spectacular dates—I spent most of the day at the cinema for One Battle after Another, which felt to me like one of the most complete and resolved movies—a real and proper movie—that I have seen in a long time, perhaps since Everything Everywhere All at Once, which has been on the top of my mind since it started streaming on Netflix and since I was looking at James Jean’s film poster last week. Both epics about ordinary family people thrown in to situations and networks far beyond their depth.

There has been a lot of great writing on the mind-bending car chase, the politics of fascism and anti-fascism, the sticky racial dynamics, and the absurdly good casting, but I haven’t read a whole lot about the family angle of the movie, which I actually found really engrossing. But here at Nostos we write about creative families, so why should this resonate? We watched Black Bag over the summer and encountered a very similar scenario.

What does it say about us that espionage and terrorism seem to make the strongest cinematic metaphors for the creative family?

Quite frankly, I think it says that we are equally unwilling or unable to separate our work lives and our home lives.

And also that the commitment to art can be as totalizing and all-engrossing as the commitment to a militant faction or a spiritual cult. And that the aesthetic impulse, the desire that motivates the urge to create and to love, is the same thing that lies beneath it all. It’s one of the first things we hear from Leo/ Pat/ Bob in the getaway car: “What the fuck do you think I’m doing here?”

Imagine yourself as Willa/ Chase Infiniti. You’re a teenager in a small but diverse town. You’re the mature only child of a single father who spends most of the time stoned and has a ton of weird rules, one of which is no phone, but you get a secret one anyway. Your dad has told you, at some point, that your mother was a political martyr, and has given you a weird device you’re supposed to carry at all times and a series of passcodes. It all sounds deliriously insane, but you have digested it and made peace with it, probably just to keep things cordial at home.

Then, one day, it all suddenly appears to be real: the device works, someone else knows the passcodes, you’re in mortal danger, and you’re absorbed into a broader underground network of people who would seemingly do anything to keep you safe. You have an extended family, kith and kin, the discovery of which both justifies and normalizes what you’ve been suspicious about in your father’s paranoid delusions.

I think that’s a pretty good metaphor for what it’s like growing up as the only child of a single parent in general, particularly if your single dad is an artist. It’s a significant variation on the traditional trope of the orphan or adoptee who discovers special powers that give them a sense of belonging within a wider web of outcasts, mutants, wizards, or heroes.

Links: Children’s Cinema, Lock-Through Power, and Cognitive Load

The Children’s Cinema at Light Industry

Light Industry, one of the coolest art cinemas, runs an ongoing series called The Children’s Cinema, which looks for ways to introduce kids to experimental film. Their next event is coming up on 25 October and has something of a Halloween theme. The way they’ve programmed it is nothing short of brilliant:

“This program is co-curated by a kid! R. Emmet Sweeney asked his nine-year-old daughter Alice to select some of her favorite YouTube memes, the ones she endlessly quotes with her friends at school. They naturally broke down into three themes: Cats, Pop Music, and Horror. Rob then paired them with a selection of silent films and experimental works to prove that so-called ‘brainrot’ has roots in early and experimental cinema, what former Light Industry guest Tom Gunning called ‘the cinema of attractions.’ So you’ll see one of the first close-ups (1903’s The Sick Kitten) alongside an earworm meme of a headbobbing kitty (2024’s Chipi chipi chapa chapa cat), a mind-melting KPop Demon Hunters remix leading into abstract animation set to an Oscar Peterson beat (Begone Dull Care, 1949), and the unspeakable abyssal terror of dead-eyed CGI gummy bears (Ich Bin Dein Gummibar, 2017) followed by silent ghostly experiments from Segundo de Chomón and Buster Keaton…and more! Happy Halloween!

“Lock-In and Lock-Through Power,” on Dare to Lead

Brené Brown’s podcast ran an excerpt from her book Strong Ground. Since everyone is talking about locking in this week I thought it would be a good moment for this one: the theory is that we need time, space, and bandwidth to shift from one mode to another, so we need to set and communicate “locking-through” rituals to transition from office mode to home mode. The lock-through is a metaphor drawn from inland navigation where ships, boats, and barges use lock systems to move up and down waterways at different altitudes—a maritime metaphor is always a winner with me. I feel like the lock-through can be particularly complicated when you’re moving from the studio, partially because we often invite friends and family into the working space and partially because hanging out time often leads to some of the best spontaneous ideas that need to be captured immediately. What kinds of rituals do you use to negotiate between home mode and studio mode?

These other links are Substacks which load a little weird as links, so dropped in with a bit less commentary.

“Move over emotional labor: it’s cognitive load time,” in Evil Witches

On the “mental workload of family life,” which is a very real thing

“The Coolest Interiors on TV are on a Kids’ Show,” in Schmatta

On the architectural set design of Shape Island, and the sophistication that kids’ visual palettes are open to when they’re given a chance to step outside the noise

“Our favorite children’s illustrator,” in Love, Sylvie

On mid-century author, illustrator, and dancer Remy Charlip