Playable Art as Public Art

This summer it's more about performing than climbing

Editor’s Note: Playable Art as Public Art

Editor’s Note is a regular column introducing issues, themes, and frameworks from a personal perspective.

I’ve just landed in Newport, Rhode Island, to visit my dad’s family after a fantastic week in London. I had expected to catch my dad in Porto, but his family, like mine, is one of those restless ones that never stays where you expect it to, so here we are, enjoying a bit of high summer in New England.

Spending time with friends’ families around the museums in London over their summer holiday, I’ve been thinking about playable art as one of the core genres of public art. The UK and Taiwan have what I would consider two of the most civic-minded approaches to public cultural resources: every museum has a considered level of accessibility to children, families, and young visitors, usually across interpretive programming, workshops, and dedicated exhibitions or features. For the last Field Trip column I wrote about the Taoyuan Children’s Art Center, which I believe is leading the way in Taiwan (although Taipei Fine Arts Museum has always had an excellent rotating children’s exhibition on the basement floor). Today in Field Trip I’m going to write a bit more about my visit to the Serpentine’s Play Pavilion.

But beyond the explicitly named Play Pavilion, there are many, many places for families to take kids to interact with contemporary art of balanced profundity and accessibility. We tend to think of playable art fundamentally as a variation on climbing structures, but there’s a lot more going on. Right now there seems to be an emphasis on theatricality and performance as a form of interaction.

In the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, Monster Chetwynd has built three theater sets based on Ingmar Bergman’s adaptation of The Magic Flute in an installation called Thunder, Crackle and Magic. Complete with costumes and props, there are more things to hide behind than climb on top of. I wonder if the turn towards theater has much to do with our photographic habits. In my experience children tend to enjoy a bit of both, some running around and some dress-up, back-to-back and in the same space if possible. This is part of the ongoing UNIQLO Tate Play series, which I find to be a really successful partnership that results in credible experiences by fantastic artists. If I lived in London I would have to have a dedicated column reviewing every one.

Also in the direction of theater, the Southbank Centre has a “recycled playground” called REPLAY by The Herd Theatre. You book a 45-minute slot, free play through what feels like a combination of a backstage area and a theater set, and then spend the last few minutes putting everything back together for the next group. Where so much child-friendly performance interaction is about dress-up and costuming, here the process feels much more architectural, which works really well as a change of pace.

Across the river, Tate Britain has repurposed another UNIQLO Tate Play commission by HoLD as a soft play sculpture. I didn’t have a child to toss into this one while we were completely, totally, utterly immersed in Ed Atkins (more on that below), but it’s meant to be based on Dorothea Tanning.

Icon: Ed Atkins

Icon is a regular column pairing canonical works of art and quotations from pioneering figures in the history of art and life.

As with so many gestures towards children, there is a latent unrequitedness I must accept and even enjoy.

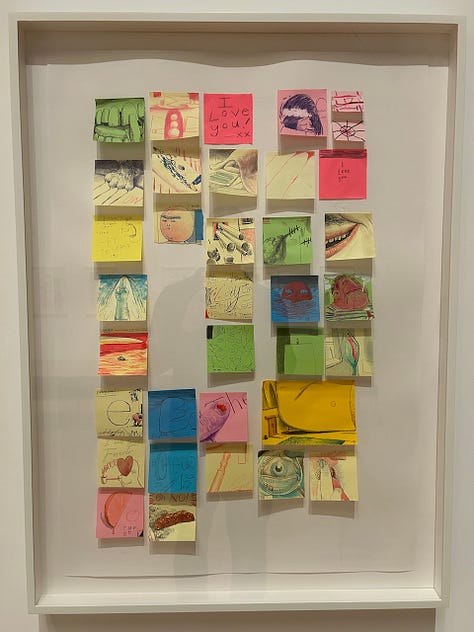

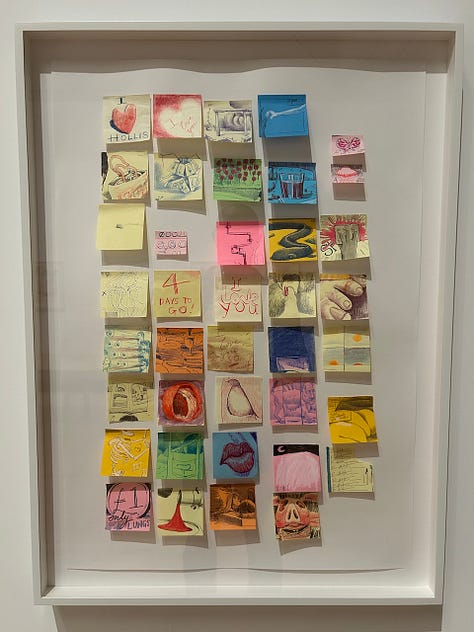

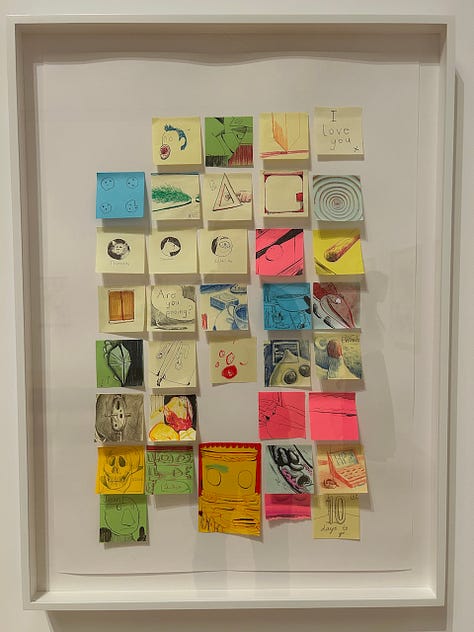

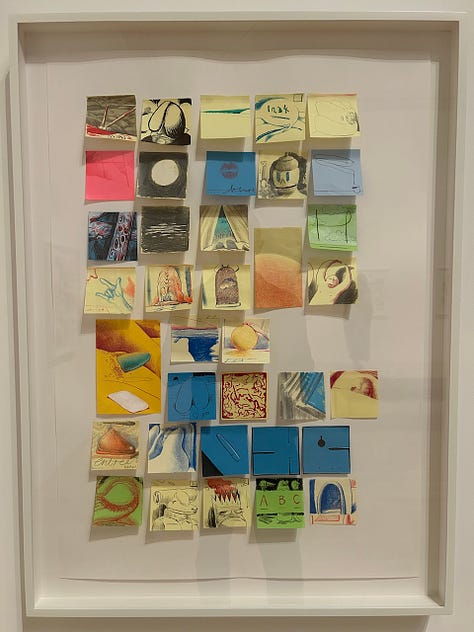

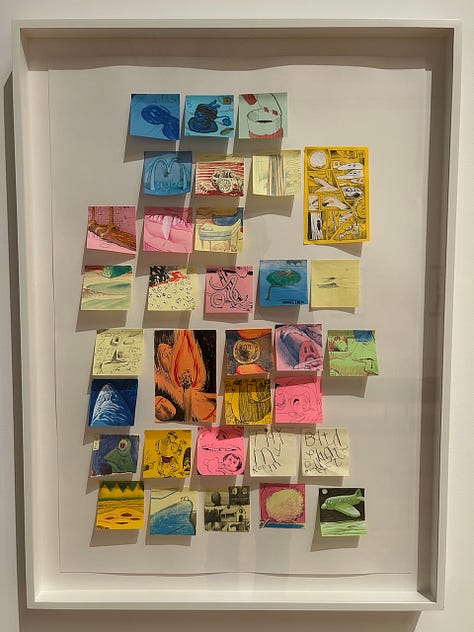

Ed Atkins on the Post-It note drawings that he has packed into his daughter’s lunches since 2020. Ed’s exhibition at Tate Britain, which I’ve written about before, was truly incredible. Where I tend to identify the core of his work with the idea of a digital avatar, this show made it much more about the idea of performance writ large. Half a room is dedicated to the Post-It note drawings, which he describes as “the cryptic legend at the bottom of the map of this exhibition and my life.” As a side note, I loved how the wall texts were written by the artist in first person. I think it goes a long way to convey the idea that the things that artists do are considered and intentional but not abstract or obtuse. He further explains these drawings:

So much of parenting is sweet mourning—for each and every moment of a child’s life that leaves, never to return, replaced by something new. … Their reach towards a marred infinite is also utterly devotional.

I am thinking a lot about practices of devotion as well as confession and forgiveness within the everyday, particularly within relationships, and want to explore this more in the coming weeks.

My first bit on Ed’s Tate Britain show is here:

Field Trip: The Serpentine Play Pavilion

Field Trip is a regular column reporting on exhibitions and institutions.

This is the first-ever Play Pavilion at the Serpentine and given the iconic status of the Serpentine Pavilion in bringing architects to global attention we can expect this to equally be an important summer destination. It feels inevitable after the success of the miniature playground built into Minsuk Cho’s pavilion last year. If adults want a nice spot for a cocktail party and a coffee bar, children want something to climb or something to build.

The inaugural commission went to Peter Cook, the legendary founder of Archigram, who was tasked with working with Lego to make the Play Pavilion happen.

Kids I know who got to play in the pavilion found it fun to work with Lego outdoors, giving it a bit of a sandbox kind of feeling. They also liked how you could make something and add it to the structure of the pavilion alongside other people’s contributions.

I visited on a gray afternoon and the pavilion seemed to always be at the edge of capacity. My main observation was on how key the staffing has to be. Having enthusiastic and extroverted play partners makes or breaks the experience for shy kids who need to be given instructions as to what can and can’t be done, a verbal outlining of the rituals that enable the freedom of play.

My feeling is that it is difficult to do something radically (disruptively) creative with Lego as an artist or architect because the thing itself provides such a strong set of expectations for the experience. In some ways this makes it fun for visitors: the person playing with the Lego blocks is contributing as much as the architect who put the structure together. But if the task of the architect is to produce a novel environment for play, something more is needed—either a restriction that forces a different kind of creativity or an unexpected context that encourages new ways of relating to them.

Jan Vormann’s use of Lego bricks to repair damaged masonry, for instance, is always surprising, but it’s a particular project. It doesn’t invite collaborators.

The best-known artist Lego work is Olafur Eliasson’s Collectivity Project or Cubic Structural Evolution Project. It’s currently on view in his exhibition at Taipei Fine Arts Museum, positioned in a broad corridor outside the exit to the exhibition proper at a junction where viewers might decide to exit towards the lobby or turn upstairs or down for other exhibitions. It’s defined by its monochrome nature (all the bricks are white) and its verticality (the default structures erected by the artist are imaginative skyscrapers). It’s hard for kids to contribute much to the main structures, though some older kids and adults do try. Most kids build little things in the trough.

Cubic Structural Evolution Project is also on display at the Haus der Kunst in Munich as part of the “For Children” exhibition, which I’ll revisit as another Field Trip column soon.

Learnings: Jin Meyerson

Learnings is a regular column that digests some of the lessons from the Lives of the Artists column.

What’s been sticking with me from my conversation with Jin comes in two bits.

First, on the very personal level, it’s his realization that it’s okay and even desirable to loosen your grip on the wheel when you have “a fantastic copilot,” as he puts it. In fact, I think we might have to take it a step further, and think about loosening that grip in order to make space for the many copilots who invariably end up around us in our lives. So often when it comes to working in teams—especially in parenting but also at work—we feel like we have to do everything ourselves and like our own way is the only way, which is blatantly inaccurate and can be hugely damaging. As a recovering perfectionist and people pleaser I’ve learned a lot about the dangers of doing too much, of becoming over-competent in ways that don’t allow the people around me to own or develop their own competencies. Better to take a step back and make a bit more breathing space.

Second, I find it interesting that Jin has been able to draw more on his biography and experience in his work with that breathing space in place. This might just be a coincidence of timing and how life happens to come together, but there also might be a little bit of causality to it. I’m going to start keeping an eye out for how much of the ethos of parenting comes through in the work among artists who have their kids running around the studio versus those who keep a bit of a buffer.

Links

“A Puppet Theater Gets Weird, With Georg Baselitz as a Guide” in the New York Times

“Oscar Murillo’s Transnational Creativity” in Frieze

Hope you’re taking the long way home.