Summer Feelings

Editor’s Note: Summer Feelings

Do you work harder or more gently over the summer? For me it is a bit of both, as it has become the season when my daughter flies to visit her mother, which lowers the guardrails of my usual routine. I do my best work in the morning, so during the school year we have breakfast together at 6:00 am and I’m at my desk working by 7:30. To reliably make that happen I need to be in bed by 10:00 pm, and there’s no more computer work after dinner time. Over the summer I find myself able to work into the evening if I’m so inclined, or to spend more evenings out, but if I do then that sacred morning work block pushes further southward into the day.

When she is away I miss my daughter and the discipline of the schedule we share. My work is less focused, but these moments of a more diffuse way of working are also useful. Travel happens on a different rhythm, and I am more inclined to pursue spontaneous conversations, or finish that book or movie or tennis match all in one sitting. I let my energies spill out in unexpected places for a few weeks at a time, and then rein them back in and direct them wherever they have been most missed.

Icon: Lina Bo Bardi

Icon is a regular column pairing canonical works of art and quotations from pioneering figures in the history of art and life.

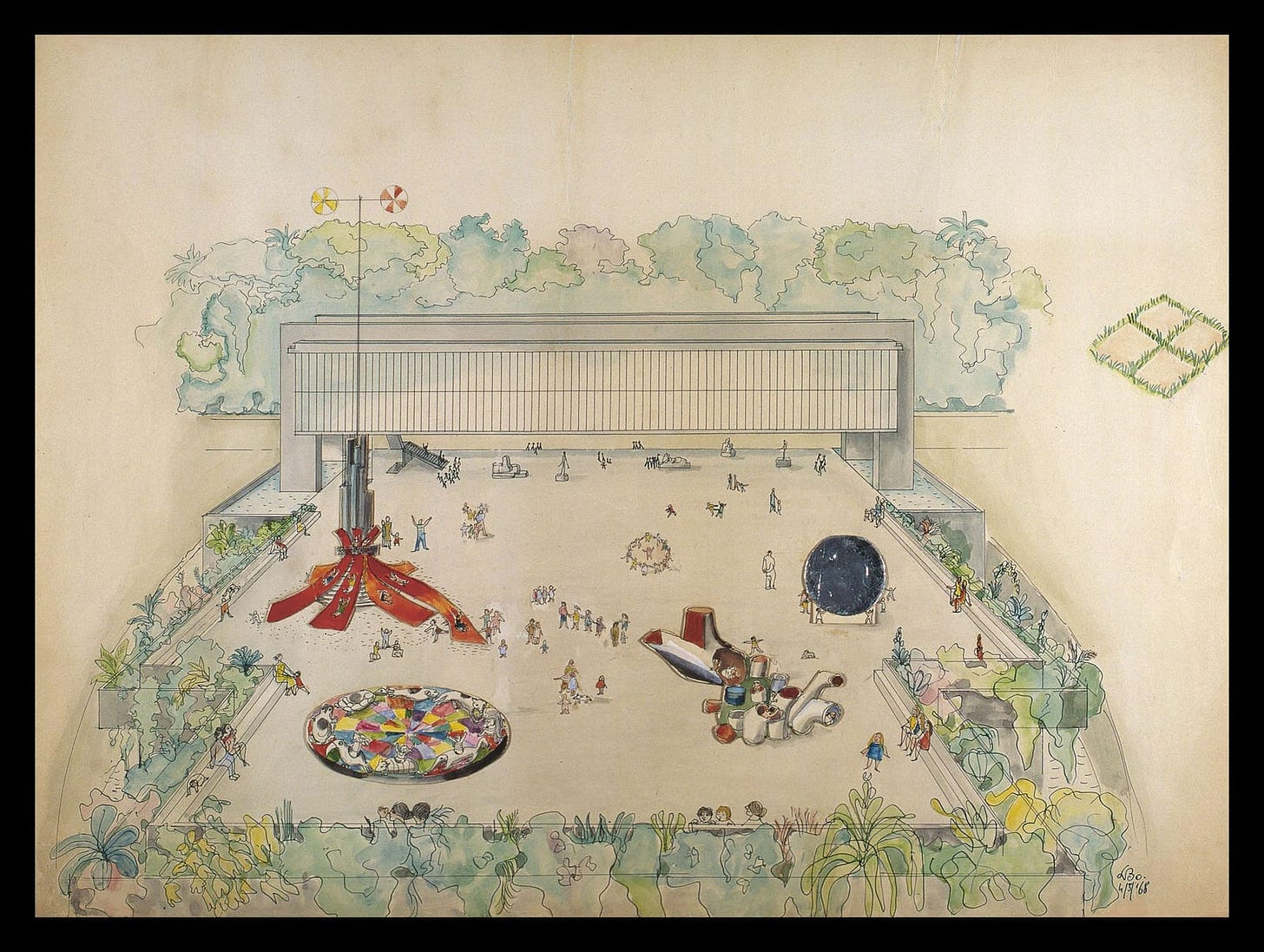

Lina Bo Bardi on her design for MASP (Museu de Arte de São Paulo). There is a punchier quote—“Every museum deserves a playground”—that unfortunately seems apocryphal. Looking at this 1965 drawing for the plaza under and in front of MASP, however, it is clear that Bo Bardi valued play in the life of the museum, mixing together a more standard sculpture garden with larger and highly interactive play structures.

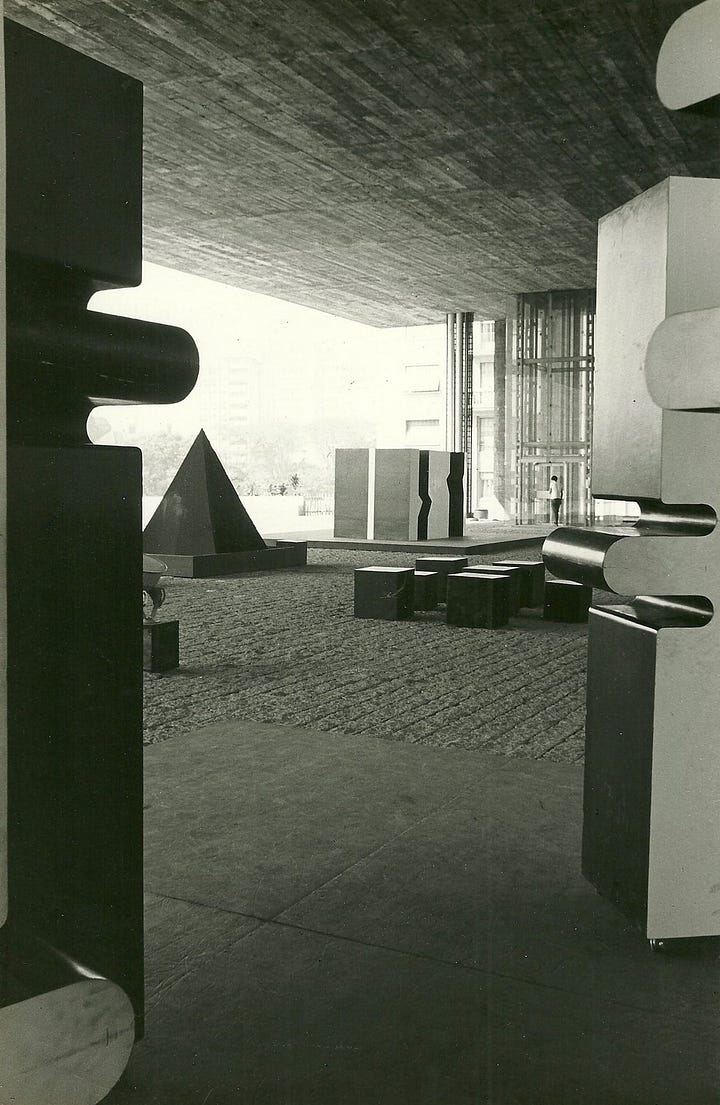

In 1969, when MASP opened to the public, this space was indeed given over to a playable exhibition by the artist Nelson Leirner (who has a funny Homage to Fontana on display at the Tate currently). Some of the views of this exhibition show abstract play structures of the kind that Noguchi and some of the other iconic 20th century figures designed. From some angles they look like prototypes, not quite coming together, and maybe splitting the difference between the sculpture garden and the play structures that Bo Bardi had imagined.

But from one angle: it’s the carousel bestiary that Bo Bardi sketched in the lower left corner of her drawing! I can’t tell if this was an homage, a collaboration, or something else entirely, but it looks like a lot of fun, and even from the photograph it seems more like a natural attraction than a staged exhibition shot.

The Lina Bo Bardi bestiary has been realized since then again by Assemble in the 2022 Nottingham Contemporary project “The Place We Imagine,” a collaboration with an initiative called Schools of Tomorrow that embedded artists within local schools and worked with students to design a play structure for the exhibition. The other two structures exhibited were designed after Bo Bardi, one adopting the animals of her carousel as soft objects, the other miniaturizing her musical slide tower.

At some point I will present more on Assemble’s work with playgrounds in general, which has spanned an initiative called Assemble Play with Penny Wilson, author of the incredible Playwork Primer, as well as the Baltic Street Adventure Playground, an ongoing public project in Glasgow, and the Brutalist Playground, a foam reinterpretation of classic architectural moments from midcentury London housing estates.

But to return for now to MASP: in 2016 the museum commissioned a group of artists including Ernesto Neto and Rasheed Araeen to respond to the spirit of the 1969 show. I don’t fully understand the politics at play, but apparently the plaza is no longer publicly accessible precisely as it was in 1969, so only a small portion of the work was able to be presented outdoors.

Field Trip: Children’s Art Center by Riken Yamamoto

Field Trip is a regular column reporting on exhibitions and institutions.

I had a chance to visit the Taoyuan Children’s Art Center for the first time. This is the second of three buildings to reopen under the aegis of the Taoyuan Museum of Fine Arts, the first being an exhibition space for the calligraphy and the third and final element being the museum itself, which is still a couple years away.

When I visited the Children’s Art Center they had been open for a little more than a year and were in the first week of a new exhibition called “When Art Meets Nature” organized with the National Gallery Singapore, whose Learning Curators do the excellent Children’s Biennale in that city (also open now, but I don’t think I’ll have a chance to visit until much later in the year). I happened to bump into the curator of the exhibition from the Taoyuan side, Peng Hsiung, as well as head of the exhibition department Lai Chih-Ting, and they were kind enough to show me around.

It was nice running into these deadpan photographs of dams by Chen Po-I; I love the work and have followed this project through a few exhibitions but would never have thought of them for a children’s exhibition. They were paired with a sensory play station where families were experimenting with shifting river flows with clay and water. I assumed that an education curator had come up with this as a way of interpreting the photographic project so was surprised to learn that Chen Po-I had designed the interactive installation himself.

The rest of the exhibition offered alternating interactive projects and quiet areas, a bit less contemporary with the exception of Zul Mahmod’s room. The murals and visuals were an oasis of cool and calm, as was the reading room for children’s books on the top floor.

My main motivation in visiting the Children’s Art Center, however, was the architecture. The building, like the main structure of the Taoyuan Museum of Fine Arts, is designed by Riken Yamamoto, recipient of the 2024 Pritzker and an architect I consider hugely important to the Nostos vision for his experiments at the boundaries between public and private space. His theory is that society can avoid being wholly captured by the interests of neoliberal capitalism through architectural intervention: if the private domestic spaces of the 20th century have led to atomization, isolation, and loneliness, then one possible answer lies in ensuring that new domestic spaces are no longer so private, that there are more marginal zones for contact between inside and outside.

This is something we talk about a lot: it takes a village, and very few of us have those anymore.

For Riken Yamamoto the concept of the threshold is key. Throughout the 1990s his commissions for multi-family housing complexes invariably included shared public space connecting the units. After 2000 the thresholds became more radical, particularly in mixed use developments, which by necessity involve the intermingling of residents and non-residents. In Niigata, the Ban Building inverts the program to give kitchens and bathrooms external windows, in part to change the pattern of light visible from the outside. In Tokyo, the Canal Court Codan combines offices and apartments, and each unit is separated from the public corridor with a transparent vestibule. In Beijing, Jianwai SOHO—where I spent important moments of my formative years hanging around Vitamin Creative Space’s The Shop, Cao Fei’s studio, and the OMA offices—every unit has a vestibule. In Seongnam, southeast of Seoul, the 100 homes of the Pangyo estate are bisected by a shared public deck for the community. Living quarters are on the floor below and sleeping quarters on the floor above, encouraging a constant flow through public space.

In some ways Riken Yamamoto uses architecture to pull together community while pushing back at demands for privacy—or isolation. The expanded community is constructed at the expense of the nuclear family.

It is too early to say much about the social agenda of the Taoyuan Museum of Fine Arts campus. The main body of the museum sits across the high speed rail tracks from the Children’s Art Center; they will eventually be connected by a sky bridge. For now, I can say that the Children’s Art Center is a beautiful structure that integrates light and nature from the park beneath it. Curators will complain that it is hard to darken galleries for video, but then they always do. So far transparency wins out, creating fun sightlines from one floor to the next, from the park into the galleries, and from corridors back into public space—space that might become a bit more fun itself when integrated with the paths and platforms of this modern ziggurat.

Projections: Caught by the Tides

Projections is a regular column on films that touch on living in a creative family.

Jia Zhangke’s newest movie is one for diehard fans. I saw it with a friend who kept asking if it was over and why we weren’t walking out. I can see why. The crossfades are cheesy, the visuals are jarring, and the plot is all but nonsensical. If you’re a fan, though, you watch it for what it is: old footage from multiple past projects shot over the modern phase of Jia’s career spliced together to tell a fresh story, a little bit like bumping into old friends in a dream and then waking up and deciding to give them a call.

Zhao Tao, who plays protagonist Qiaoqiao, is married to Jia Zhangke, and their collaboration is probably the defining relationship of their respective careers. They have worked together since Platform in 2000, and married in 2012. When everyone was younger, I thought that Li Zhubin, who plays Guo Bin opposite Zhao Tao, was a dead ringer for Jia Zhangke. Most of Caught by the Tides is drawn from Unknown Pleasures, in which Zhao Tao played an actress-model-dancer in urbanizing Datong around the year 2000, and Still Life, in which she played a woman seeking her estranged husband in a town flooded during the construction of the Three Gorges Dam. Some of it is outtakes but some of it is iconic, instantly recognizable scenes that made these films the first time around. Some of the hard work of twisting the plot around is accomplished through intertitles.

Like a sitcom you can’t quit because you’ve spent so much time getting to know the ensemble, your level of affection for Caught by the Tides will be defined by how moved you feel watching Zhao Tao struggle in and out of her singular, searching relationship with Li Zhubin from her early twenties dancing in clubs and modeling swimwear to her late forties as a supermarket cashier and member of a run club. In Jia Zhangke you don’t get character study. What you get instead is a form of social interiority, a sense that decisions are made because they are the decisions that can be made, because this is the logic of how one operates in a society with rapidly shifting ground rules.

Zhao Tao and Jia Zhangke have worked together on 11 films and have no children. As we have seen with the long-lasting sitting relationships of Celia Paul and Lucien Freud, Gwen John and Rodin, the psychological depth that comes through that kind of commitment can become a practice in its own right, neither strictly professional nor strictly matrimonial—but indeed, devotional in a religious, almost ecstatic sense.

In its concluding arc Caught by the Tides becomes Jia Zhangke’s Covid movie. I find it interesting that Lou Ye’s Covid movie, An Unfinished Film, opts for a closely aligned tack with repurposed footage of everyday life during the pandemic, as if this enforced pause on new production gave everyone the time to look back over their archives and think about how to move forward in a new way. Lou Ye, too, co-wrote his script with the well-known screenwriter Ma Yingli, who is also his wife.

Links: Digital Wellbeing, Generative AI, and Marthe de Méligny

“Is it the Phones?” in The New Yorker

In everything from the Netflix show Adolescence to the veritable raft of books on smartphone use among young people there has been a lot of hand-wringing and finger-pointing. Molly Fischer, along with a growing number of critics, thinks it might not be as simple as pinning the blame on the internet, the phone, or social media. I feel this shifting slightly for me now as we start looking into ways to build healthy relationships with technology rather than writing it off from the beginning.

“Youth Wellbeing in a Technology Rich World” from MIT

A lot of this is written in peer-reviewed academic language that isn’t very interesting or accessible for non-specialists like me, but there are some interesting bits in how the experience of young people might be better taken into account in designing the interventions into digital hygiene that are so desperately needed.

“Synthetic Images; Real Feelings: Generative AI and Teen Well-Being” from NYU

This one was particularly interesting for me because my daughter’s social group has been dealing with their relationships to AI chatbots, which they seemingly connect to for company and to explore topics they don’t feel comfortable broaching in real life, or what this report refers to as “self-concept development.”

“In the Bath, Forever: On Marthe de Méligny” in Selavy

Completely unrelated to this digital stuff, but thinking about the kinds of intense painter-sitter and actor-director relationships that we find among romantic partners who are also creative partners reminded me of this piece on Pierre and Marthe Bonnard (who are apparently the subject of a recent film that I have been trying to track down). Selavy has become one of my favorite new art publications, though many of the writers and some of the people written about seem to be fictional, so like most criticism it is best read as literature.

Hope your road home is a long one.