The Unsolved Formula of Love

Shiny things from Klimt, Craig Mod, Cindy Chao

Icon: Klimt

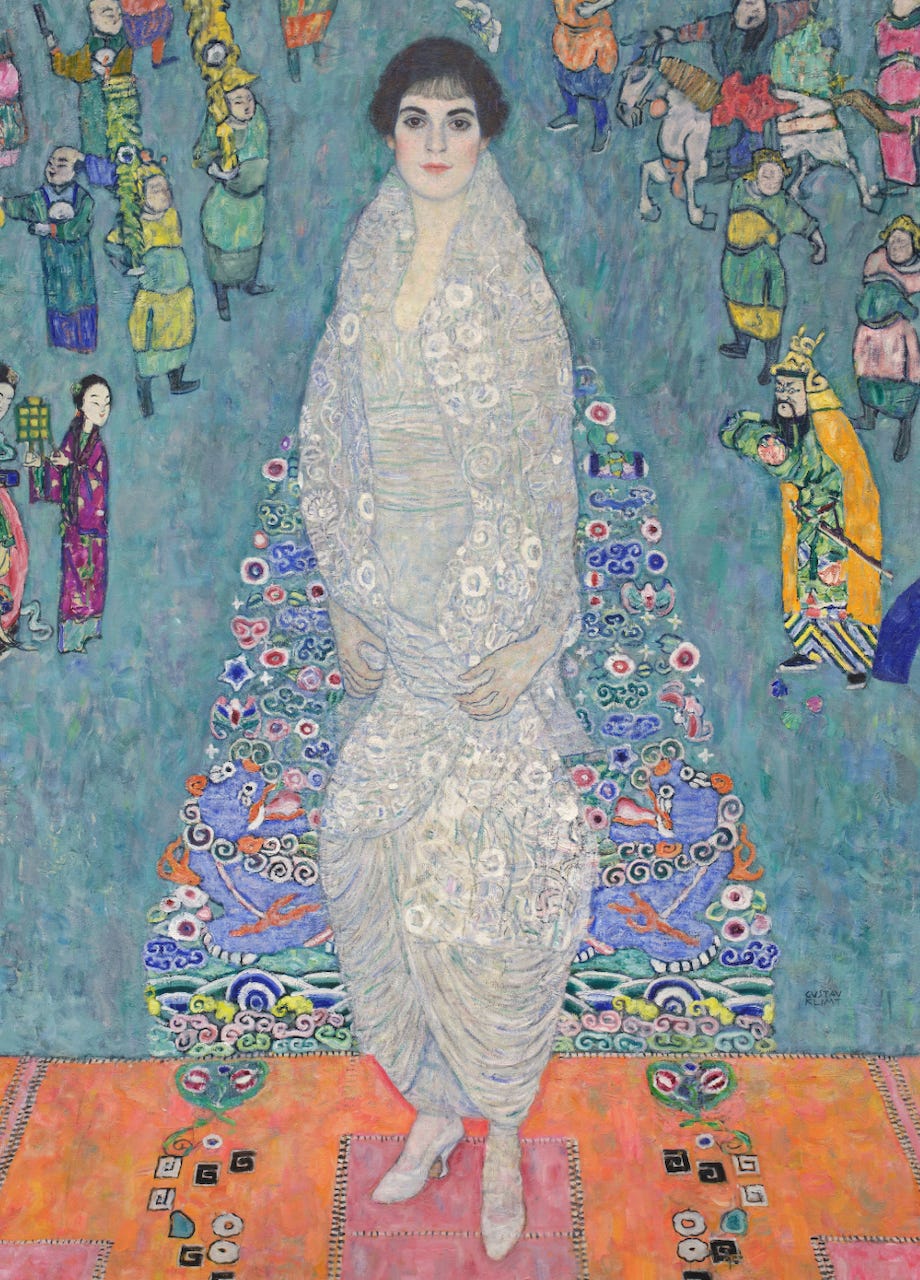

There is a beautiful 1916 Klimt coming to market as part of the Leonard Lauder collection at Sotheby’s on 18 November, the portrait of Elisabeth Lederer, a beshawled young woman poised like a mongoose on the plain. Like all Klimt portraits she is striking in costume and countenance as well as context. Reading into the backstory of the painting, we learn that it was commissioned by Elisabeth’s parents, Serena and August, “the artist’s most important patrons,” according to the catalogue note.

An earlier 1899 portrait of Serena herself is in the collection of the Met, a pretty picture that pales in comparison to the complex geometries of shawl, cape, and field, across which figures from Chinese design marshal themselves in salute. Photographs of Klimt’s studio from this era show the minimalism of Secession/Werkstätte furniture offset by the rich symbolism of Chinese court painting and folk art, an impressively cosmopolitan juxtaposition that makes its presence felt in this Jewish society portrait, too.

The story of Klimt’s relationship to the Lederers is significant. When his work on an official state commission attracted criticism, the family acquired the work from him directly and paid back his honorarium; a series of further acquisitions and commissions followed. Klimt died in 1918. During the Nazi takeover of Austria, Elisabeth was divorced, her father died, and her mother went into exile. Together, Elisabeth and Serena testified that Elisabeth was the biological daughter of Klimt, giving her a claim to Aryan blood. (By most but not all accounts this was not actually the case. The artist is understood to have had as many as sixteen illegitimate children, four of whom he recognized during his lifetime.)

One of the ongoing fixations of our research here is on the relationship between the artist and the sitter, and this may be one of my favorite stories yet. We have seen with Freud, Rodin, and many others how the aesthetic attraction between artist and sitter can become sexual and/or romantic, sometimes violently so. In other cases, certainly, the pairing of patron and artist has resulted in affairs of the heart. In this case, however, it is an intertwining of artistic lineage and family genealogy: Klimt did indeed give art lessons to both Serena and Elisabeth, and a part of Elisabeth’s case to the regime was her artistic talent. She reinvented herself as an artist, perhaps as part of the ruse and perhaps as a way to move through her divorce and the death of her son.

Oddly, the party functionary in charge of Vienna, Baldur von Schirach, was a fan of modern art in spite of the official dictum of the regime, appropriating works from the Jewish families at his pleasure and celebrating Klimt with a 1943 exhibition at the Belvedere. As portraits of Jewish society, however, the Lederer portraits were excluded. John Geddes has a delightful take on this moment in history, tying together Klimt and Carl Moll, a Secessionist who became an ardent Nazi supporter, and his stepdaughter, the formidable Alma Mahler, who we will have to catch up with separately in another essay.

Many of these social structures were treated in the 1917 Neue Galerie exhibition “Klimt and the Women of Vienna’s Golden Age, 1900-1918.” That show brought together both Elisabeth and Serena with the two portraits of Adele Bloch-Bauer, some of Klimt’s most celebrated. When I started reading into the stories about Klimt’s relationships with his other sitters, I quickly landed on Emilie Flöge, with whom he kept up a correspondence and companionship for 27 years. She was the younger sister of his brother Ernst’s wife, and they became something of a blended family after Ernst died unexpectedly.

Klimt and Emilie were partners in public life (on the Viennese ball circuit) and in their creative practices: Emilie became the creative director of her family’s couture operation, and dressed many of the women of Klimt’s portraits, while many of the patterns that would become his signature come from her work. He sometimes designed the dresses she would create for his sitters. The creative dialogue between paint and textile is evident in just about every mature Klimt painting. I imagine that Charlie Porter’s Bring No Clothes would find a beautiful sequel in this epoch of Vienna.

Klimt was not much of a writer, but he wrote some 400 letters and notes to Emilie, which constitute the bulk of the visibility we have into his thinking about his own life. There is nothing whatsoever about the romantic side of their relationship, if there was one at all. Irina Olikh called it an “unsolved formula of love.”

He gave financial support to some of his paramours, at least those who were professional models rather than those who were his patrons, and wrote perfunctory notes inquiring after the health of his children during their younger years, but appears to have lost interest as they matured.

But speaking of children. The Neue Galerie exhibition also included the Portrait of Mäda Primavesi (1912), which I will end on. Mäda was nine or ten years old when she sat for the portrait, the daughter of another important patron couple (in fact, the core patrons of the Werkstätte) and she’s the most badass sitter of the bunch. Her portrait was sold by the family early on in the upheavals of occupation. She settled in Canada, where she founded a children’s hospital, and sold Klimt’s portrait of her mother, believed to be lost until it came to auction, when she prepared to put her estate in order in 1987. The New York Times tracked her down, then the last surviving of the women of Vienna’s golden age, and she recalled the parties in which Klimt wore Emilie’s flowing robes. She said that Klimt was “awfully kind” when she became impatient over the course of the “200 sketches” he made in preparation for the portrait. He left her an inscription in an autograph book: “The day is like night unless I see you. I am happier if I dream about you.”

That’s much more than any of his biological children ever got, at least in writing. Better a muse than progeny—some of the artist fathers seem to have done their best parenting posthumously.

Book Report: Things Become Other Things

Before Substack exploded and became what it is now, it was Craig Mod’s newsletter practice that opened my eyes to the email format as a serious literary endeavor, not just a way to market what one might be doing elsewhere but rather a way to sit with readers where they are, in the domestic space of the inbox, and have conversations of some profundity and utility. He is one of the sharpest thinkers I have had the pleasure to read, knowledgeable on everything he touches, both because he is patient and caring enough to put in the research on whatever field he writes about and because he is daring and vulnerable enough to position himself in those spaces, willingly learning in equal parts from his body, his mind, and their shared experiences of the greater world beyond. Subscribe to his newsletters.

Craig’s main methodology is walking. He has group walking projects, which necessarily involve much more conversation and social interaction, both within and external to the group, and he has solo walking projects, mostly in Japan, often over the same routes. He does scary things like talking to strangers just for the sake of the conversation, often asking to photograph them. His walking memoir, Things Become Other Things, is a record of one such solo walk along the pilgrim trails of Japan’s Kii Peninsula. In it, he makes cultural observations about the sense of abundance and security he has found in the Japanese social fabric, in stark contrast to the hollowed-out post-industrial towns of his youth. Near the closing pages of the book, he writes about the children he encountered on the Kii Peninsula:

Even here, even on this peninsula where youth is vanishing, on weekday afternoons, toward the end of a long day of walking, the elementary-school kids are let out and roam about. Village or town or city, makes no difference, elementary-school kids walk as elementary-school kids walk. They have nowhere to be and nowhere they want to be but in the walk. Supple bodies bending and twisting as they shuffle forward, jumping, crouching low, pushing one another over, bouncing back up. They walk, and don’t even know it as walking. In this way, they are ideal walkers, and have found the true walk. Their walk is a walk of peace, of a collective social decision to allow it to happen. Eyes are on them. Eyes peering out from behind hedges and eyes beside pushed-back curtains. Eyes attached to adults who care, who have the yoyū [abundance] to care, who watch at a distance. Their freeness of walk is a product of a cascade of this support. The kids don’t know this but they feel it, show it in every little yelp. They bump into one another and speed up and slow down. They run alongside rivers with their umbrellas held behind, like miniature fighter jets landing on aircraft carriers surrounded by dandelions.

It’s a beautiful piece of writing and a beautiful sentiment. Craig writes a lot about his own family background and I, as a nosy reader, follow a lot of his interviews and other appearances as well. In a couple podcasts earlier this year he told the story of how he recently tracked down his birth mother, and certain aspects of his personality and way of being in the world clicked into place. He talks about his adoptive mother, too, about how she saved up money for college tuition before she knew how badly someone like him would need to get out of their environment. To think that this is what we are, formed in some directions before we are born by things we cannot know and cannot explain, and then molded in other ways by the very tangible, circumstantial boundaries that we push up against on a daily basis.

Living with awareness might be little more than accepting that, just as we are shaped by these sets of things, we are responsible for the accidental, incidental, and intentional shaping that we give to things in turn. This isn’t exactly what Craig means by “things become other things,” but it also isn’t alien to his project. He dedicates the book to a child who is his daughter in mind if not in law:

Her life force cracked open my heart in a way that allowed me to go back to him, to revisit what we had and didn’t have as kids.

One of the greatest gifts we get from our children, wrapped as it is in Pandora’s Box, is the opportunity to ride the elevator of experience back to our own childhoods, to relive, rethink, and relearn the lessons we missed the first time around.

Project: Cindy Chao

Last weekend my friend Yuting and I put together a creative workshop for children in the context of an exhibition by CINDY CHAO, the extremely high-end art jeweler whose pieces are de rigeur in collecting circles across Taiwan and China. This season, Cindy invited the artist Yu Wen-Fu to work with her on the space, and he used his signature bamboo material to create a series of rectangular volumes and cylindrical hubs in which to display Cindy’s jewelry. One of Cindy’s ongoing concerns is the feather, and in her newest body of work she has worked wonders with titanium settings to create feathers and leaves that are truly sculptural objects in the round.

For our workshop, Yu proposed combining feathers and bamboo: the kids were invited to cut duck feathers to create little winter dioramas. It was a lot of work and all of the parents had to pitch in on the feather-snipping assembly line, but the results speak for themselves. Bringing the kids around the exhibition space made for a strikingly different atmosphere, and I dare say asked all of us to look at the work with fresh eyes. The best part for me was watching how each kid took their project in a different direction: my daughter, ever the contrarian, perched her figurines on the tops of her trees and face-down in the snow. Our neighbor, the daughter of a boutique owner and a theater producer, researched what everyone else was doing before going her own way and sending her figurines along a path into the forest.

My photographs of Cindy’s jewelry are too amateurish to do it any justice by reproducing here, but you can take a look on my Instagram.

Links: Rachel Cusk and Catherine Lacey

Two beautiful recent short stories from the trenches of autofiction, two of my favorite writers thinking about what it means to inhabit a life from the perspective of another:

“Project,” in the New Yorker

Rachel Cusk: “It might be said that creative people were people whose childhoods hadn’t ended. There was no particular basis for thinking this, other than the fact that most children created things and most adults didn’t. In a way it was terrible, the idea that childhood might not end.”

“Coconut Flan,” in the New Yorker

Catherine Lacey: “She tried to imagine the sound of someone putting her lost keys, their found keys, into the lock and turning the knob and entering her home. She thought so much about this possibility, with such focus, that she was quite sure she knew exactly how it would feel, finally, for some other character to enter her life, ready to repossess it as their own.”

I’ll be back next week with a piece on David Hockney’s double portraits that I’ve had a great time researching and working on. Until then, enjoy the long road home, and stay in touch.