The Lady Painter and Her Conjugal Yoke

Biala, Lauren Oyler, Caroline Walker

Icon: Biala

Icon is a regular column pairing canonical works of art and quotations from pioneering figures in the history of art and life.

“Lady painters; they seldom appear in your pages detached from the conjugal yoke.”

That’s Biala in a letter to ARTnews, expressing her frustration at being contextualized as someone’s wife or brother: “I have never been given a review in your journal unaccompanied by one dear husband or another, and now the secret is out. I have a brother too!” With apologies, she will have to remain frustrated today as we look at the social graph of her artistic lineage, because that’s what we do here, but rest assured—we are looking at her paintings on their merits alone.

Biala’s work caught my eye in a couple previews of the fall season. Berry Campbell dedicated their Frieze Masters stand to her work, and indeed it was the work itself that grabbed hold of me and wouldn’t let go; I knew nothing about her story until I went digging. The first story is always visual: starting with her earlier work of the 1930s one finds genre pieces (street scenes, interiors, still lifes, group portraits) teetering on the edge of dissolution, chunks of paint pushing in and out of their compositions, until the 1950s when they let go and relax into the wind of gestural abstraction, and then finally in the 1960s and 1970s land anew in lighter, more suggestive places. There is no dull phase across her oeuvre.

As of yesterday, Galerie Pauline Pavec has opened a solo exhibition of Biala’s work in Paris, giving her an epic Channel Slam. If you’re in town for Basel I hope you can make it over to see these paintings in person. The exhibition will be on view through 20 December.

Biala was born in Poland in 1903 and immigrated to New York with her family at the age of 10. She brought her brother along with her to art classes—and he became the abstract expressionist painter Jack Tworkov. She changed her name to Biala to avoid confusion. In 1930 she traveled to Paris and promptly met the English writer Ford Madox Ford, some 30 years her senior, and entered into a love affair that would last until her partner’s death in 1939. How I love a cross-disciplinary creative power couple. Together they spent that decade in the company of Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, Picasso, Brancusi, her idol Matisse.

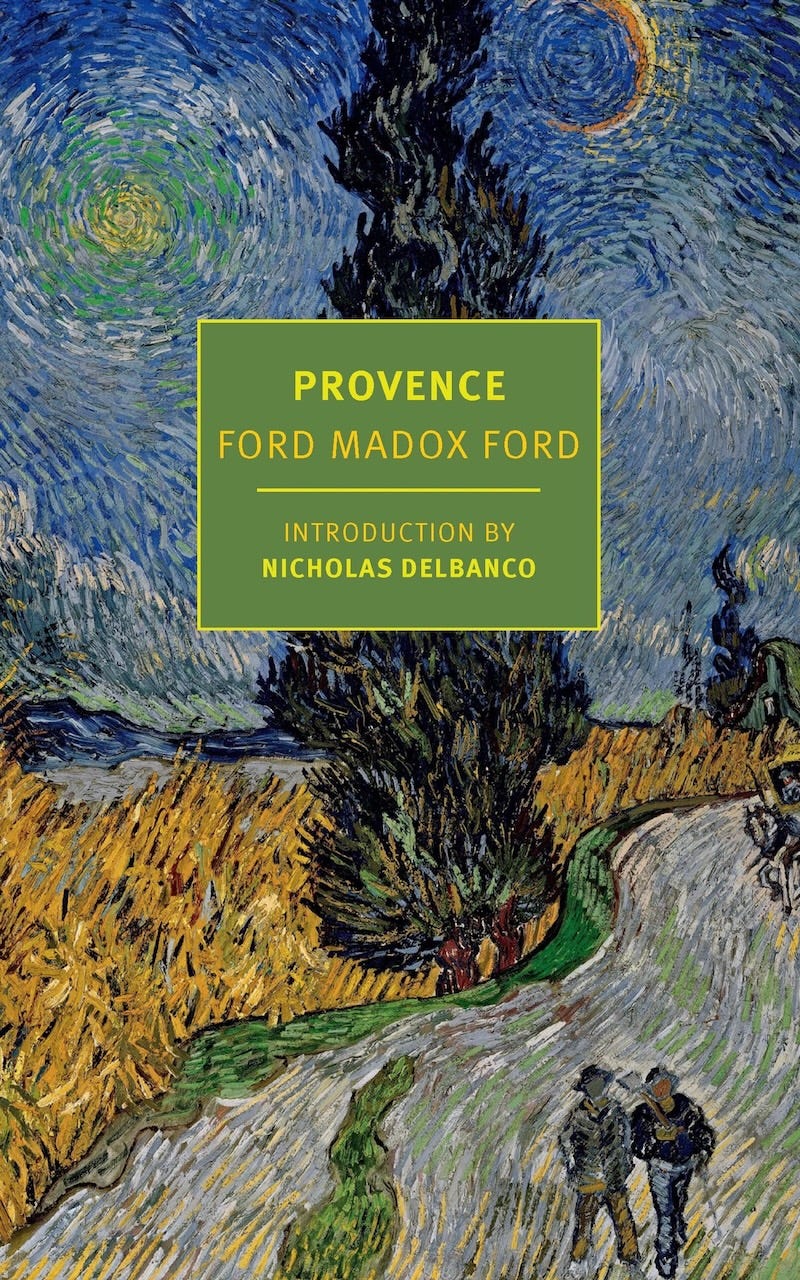

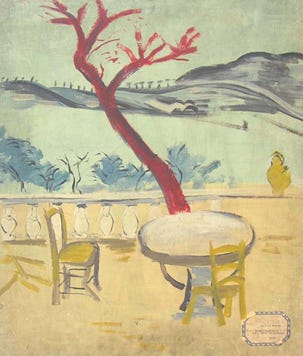

To frame her legacy this way: to speak of her conjugal and fraternal yokes, to put the biography directly beside the pictures, to wonder about her as a person. Does it devalue her contribution as an artist? Artists are so often suspicious of biography, particularly when they come from (or initiate) illustrious lineages like this one. Everything, after all, is already in the work. And this is the fun of it. We can look at Biala’s early paintings of Provence, which she developed out of illustrations that she made for Ford’s travel memoir Provence and then exhibited in a gallery solo exhibition back in New York. Knowing that she and Ford shared a hardscrabble, romantic existence gardening, drawing, painting, writing, and loving in a house outside Toulon is not to try to reflect the stolen valor of one’s career on the other but rather to admire with some degree of wonder how they were able to put it all together.

Provence will be reissued by NYRB Classics in June of next year, just in time for a pilgrimage to the Villa Paul in Toulon. Max Saunders has done the heroic work of tracking down the location of the house based on views of the area from Biala’s paintings, and his adventure in doing so is well worth a read. It is also from Max’s account that I have borrowed these two paintings of the terrace of the house in Provence, one by Biala, one by Stella Bowen, Ford’s paramour throughout the 1920s; apparently Stella and Julie, her daughter with Ford, stayed in the house in the winters once Ford and Biala had returned to Paris. Stella, too, provided her services in illustrating Ford’s books during their time together. Later she would return to Australia and become known as a war artist.

War painting is not something that particularly interests me, and I would surely have passed over Stella’s paintings entirely had I not noticed this little bit of connection. In this bit of biographical sorcery, it is not her connection to a famous man that lifts her up but rather the improbable inversion of loose and louche paintings of the Provence coast into propagandistic portraits of bomber crews. What a life.

In 1939, Ford died and the war came to France. Biala made a daring rescue of his papers from Provence before returning to New York, where she circulated among the New York School, a vortex with her brother at the center. In the summer of 1942 she married Alain Brustlein, a painter and prolific illustrator of New Yorker covers. It was Biala who introduced Willem de Kooning to her dealer, and she and Alain nursed him in ill health, and celebrated his wedding to Elaine. They returned to Paris after the war in 1947, and split the rest of their lives between France and the east coast—the city, as well as Provincetown and rural New Jersey. Back in Paris, Biala’s shift towards abstraction sat alongside Joan Mitchell for those middle decades. There is one knot of a painting from 1959 in the Pavec exhibition that is just stunning. You can and should look closely at these beautiful pictures here.

For me it is the tabletop still life that offers the ultimate line through Biala’s life: dark and heavy or nearly floating, ordered and rectilinear or chaotic and naturalistic, sparse and scattered or dense with symbolism, captured from directly above or from a skewed low angle. We see in these pictures the shape that Biala gave to her life, how she picked up and turned around in her hands the substance of it all.

The fascination is unending. Did you ever read the Little Bear picture books? Little Bear’s Christmas? Somewhat improbably, these are yet another of Biala’s contributions to the culture. And the rest of Biala’s clan: her niece, the painter Hermine Ford, and Hermine’s husband, the painter Robert Moskowitz. So many corners of this story remain to be covered: the give-and-take between painting and illustration in Biala and Alain’s shared upstairs studios in Paris (8, rue du Général Bertrand for those piecing together the pilgrimage), Tworkov’s defection from abstract expressionism towards geometric abstraction and his own notes published as Extreme of the Middle: Writings of Jack Tworkov. In addition to the galleries I have mentioned here, much of these notes are drawn from research gathered by the brilliant painter and scholar Mira Schor and Jason Andrew, who works on the Biala estate.

Book Report: No Judgment

Book Report is a regular column that reads books for, by, and about artist parents.

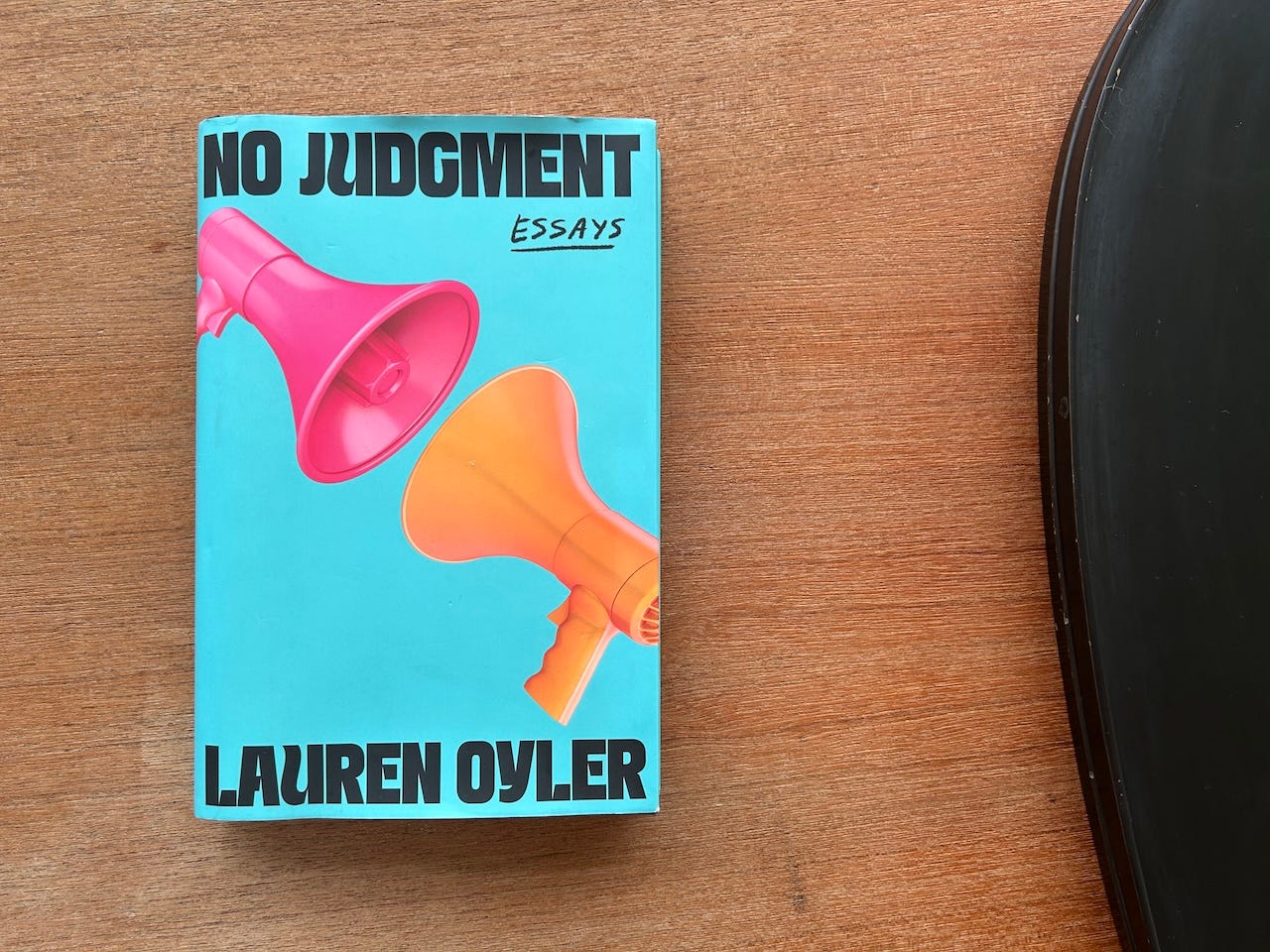

How much should we be aware of the artist’s biography as we try to understand the work? When is it a distraction, and when is it actively harmful? These are questions we are constantly returning to as we figure out how to look at the interface between art and life. The critic and novelist Lauren Oyler talks quite a bit about the relationship between these two sides of her practice in her essay collection No Judgment, particularly in what she describes as “my autofiction essay,” “I Am the One Who Is Sitting Here, for Hours and Hours and Hours.” Early in the piece she gives us what will have to pass for a definition.

What It Isn’t: A piece of fiction that merely draws on an author’s life. A selfie. Social media. Reality television. Fiction about cars. I’m not saying that autofiction isn’t like any of these things; in fact, autofiction is like all of them. However, two things may share similarities without completely transforming into one another. This is an important lesson for romantic relationships as well as for literary criticism.

Visual art is interesting to put alongside conversations like these. I tend to think of the blurring between autofiction and memoir and fiction as something akin to the near-constant vacillation between figurative paintings and abstraction that happens in art—which is to say, some things become more or less popular in reaction to what people are currently finding more or less popular, but no one can really stake the battle lines anywhere meaningful. Also, where a novel requires some degree of plot, which can be systematically compared to the arc of the author’s life if the reader is so inclined, a painting is simply a moment in time, a condensation of many different experiences that may or may not occur to the artist in a first-person kind of way. We assume that many of Biala’s still life configurations were housed at 8, rue du Général Bertrand, but we wouldn’t fault her for borrowing a memory of a tea set from the Villa Paul. Does this make painting inherently less honest than writing, or rather, both more and less honest, because it is held to a completely different standard? It certainly makes it more interesting to play the game of drawing biographical conclusions from painterly hints.

Lauren continues

Autofiction is a form more than a genre. … Autofiction is sometimes called a genre because it is first and foremost fiction—that’s its structure—and because autofictional novels could be said to follow certain conventions, such as the inclusion of references to the writer’s career, critical digressions about external works of art the author-narrator encounters, and a moodily naturalistic style. But I’m arguing it’s better to call it a form. In nonfiction, ‘what really happened’ is the form; in fiction, the form is possibility, again broadly construed—what might happen, what might have happened, what might happen if. This possibility may or may not involve an authorial avatar. In autofiction, the form is the author himself.

You have to live a life, in other words.

Autofiction tends to dispense with Barthes’s old-fashioned reality effects: the detailed description of a sitting room—say, for the purpose of accumulating evidence of realism—is seen, in the context of the otherwise verifiable autofictional narrator’s voice, as pointless.

This is fascinating because it is exactly the opposite of what happens in first-person painting. In a Biala still life, the “detailed description” is not there to “accumulate evidence of realism,” but rather because it is the substance of the life that the painter is living. Not proof of life presented for witness, but life itself that is executed in its very production. The tabletop still lifes, the tree outside the terrasse in Provence, the cluster of cornflower blue brushstrokes. No degree of abstraction or obfuscation speaks any less clearly about the liveness of the moment.

... as a critic and reader I know that people who have read both Fake Accounts and this essay—any of my essays—will necessarily, consciously or not, be reading them in some way ‘together’: that the essay will shed light on the novel and vice versa.

This is how we read art and life: together, side by side, intertwined, inextricable. Because art, like it or not, is necessarily the product of a life, a series of lives that intersect and create the conditions for art to emerge at a particular point. And life, of course, is something that happens to us while we are trying to write autofiction.

As a form, autofiction is about self-awareness; it represents self-awareness formally.

Lauren goes on to discuss the ethics of including material related to other people in autofiction, and the pressure to put everything interesting that happens in one’s life into one’s art, concluding that everything is fair game, the label of fiction is not particularly important, and the central mandate is simply to be interesting. We write because “we take what’s there and imagine something new or simply different.” In another essay she analyzes vulnerability and the gender dynamics of how we relate to truth, trauma, and disclosure in literature, which is another conversation waiting to happen, but I want to end here on the idea of self-awareness and connect it back to the idea of “painting beside itself,” the social diagram of the artist’s relationships that we often see in practices of portraiture and still life—the genres of immediacy before immediacy.

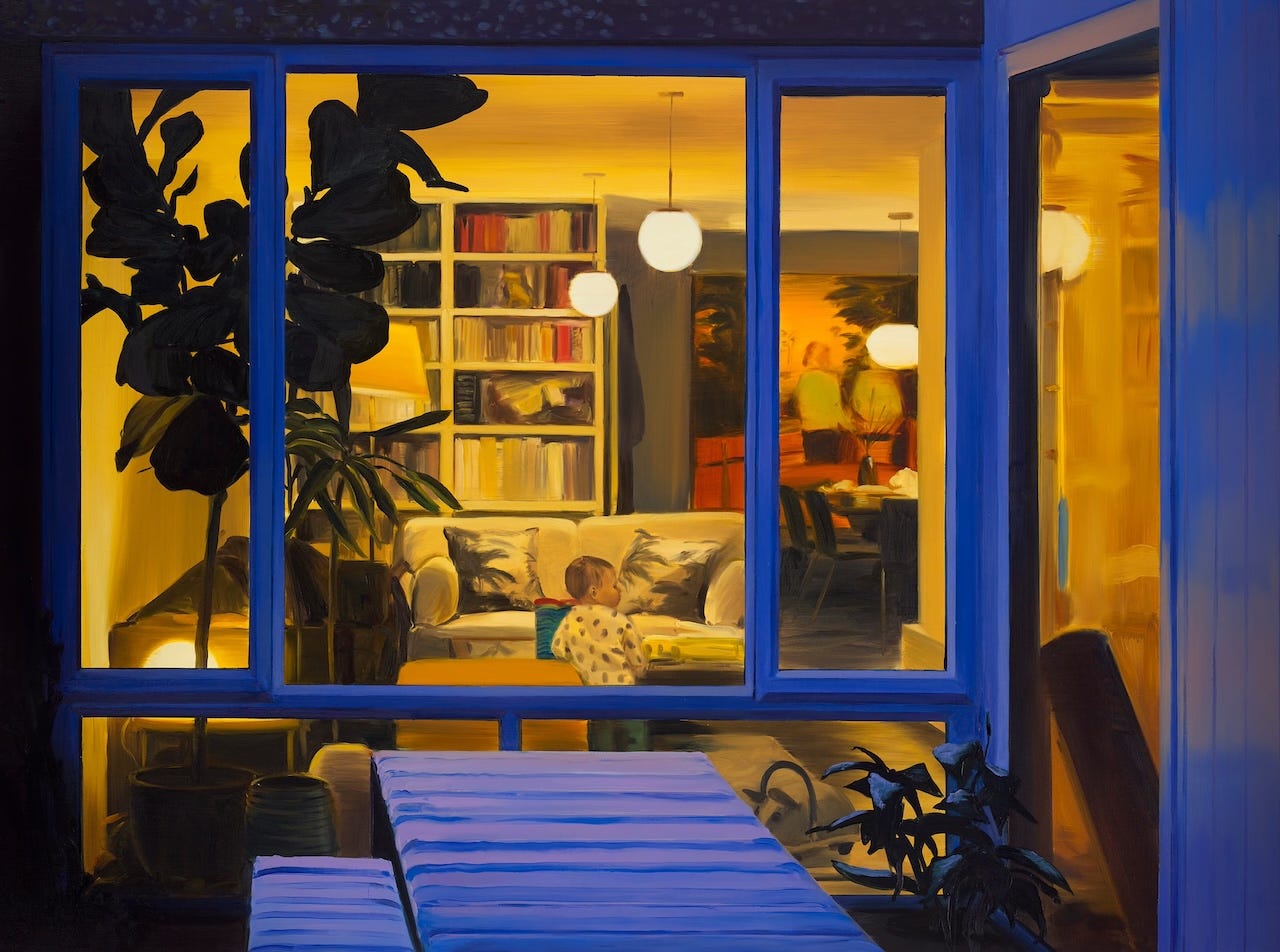

Field Trip: Caroline Walker at the Hepworth Wakefield

Field Trip is a regular column reporting on exhibitions and institutions.

Although this is already getting quite long, I wanted to close with a brief nod towards Caroline Walker’s brilliant exhibition at the Hepworth Wakefield closing this weekend. Caroline is a painter who we will no doubt revisit often here because she is such a tireless advocate for women’s experience and women’s labor in contemporary art, advocacy that is evident in both subject matter and practice. She paints women. They are often alone or with a child. They seem to appear between private and public space. They are sometimes people very close to her and sometimes people laboring in situations that seem almost anonymous. They provide a diagram not only of her own situatedness in the relationships that define her life, but also the situatedness of society at large, a mapping of what womanhood means across architectural spaces, employment arrangements, and family configurations.

In Lauren Oyler’s critique of “being vulnerable” and “relatability,” there is the corollary effect of “feeling seen” (or the sarcastic “feeling attacked”), one of the primary pathways through which the reader-viewer is able to situate herself in relation to the work of art. Caroline’s paintings seem more like vehicles for feeling seen than windows into a specific embodied consciousness. This is her reality effect.

Caroline’s exhibition is called “Mothering,” and the paintings in this exhibition are largely of herself, her children, her life. (Though not all: the series “Birth Reflections” was painted during a residency in the maternity ward of a London hospital.) The Hepworth Wakefield published a print of a scene from her daughter’s nursery school. A viewer might still feel seen, but in this new exhibition we additionally gain more visibility into her life. As she told the Guardian:

A lot of the time, I’ve been looking in on a subject as an outsider. I was paying for another woman to look after my child, so that I could make my work, which in this case was portraying that woman looking after my child. There was a complicated relationship of financial exchange going on that made me think about how we value different forms of labour.

Links: Transit Books, Kids Curating, Essential Childrens Books

Transit Children’s Editions Book Club

One of the best independent publishers out there, particularly for literature in translation, has launched an imprint for children’s books, which now has a book club (though book club here unfortunately means pay in advance to have newly published books delivered to you, not sit with a group of like-minded individuals in a pro-social environment to discuss art and ideas). Their picture books look delightful.

“One Way to Shake Up Museum Curation? Hand the Keys to the Kids,” in the New York Times

Ray Mark Rinaldi looks at a bunch of American museums with educational programs that allow community members, including children and teens, to participate in the curatorial process, hopping from the Orange County Museum of Art to the Clyfford Still Museum in Denver and the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. I think these can be great projects, but also have a sneaking suspicion that, like German museums pushing exhibitions for children, involving children has a way of sidestepping the sticky political realities that are making life for non-profits so difficult right now.

“65 Essential Children’s Books” in the Atlantic

I have done pretty well on this list, except for everything published after my daughter came of independent reading age. I feel a bit betrayed that there is no Dahlov Ipcar included. One day I’ll write about all the outstanding Maine literature for children and why I think our home state has become such a beacon of wholesome childhood.

Until next week, hope your road home is a long one.