Shorts: Hervé Guibert, Annie Ernaux, Ruth Asawa, Rose Wylie, and Ed Atkins

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Shorts is a regular column with links and commentary on family culture.

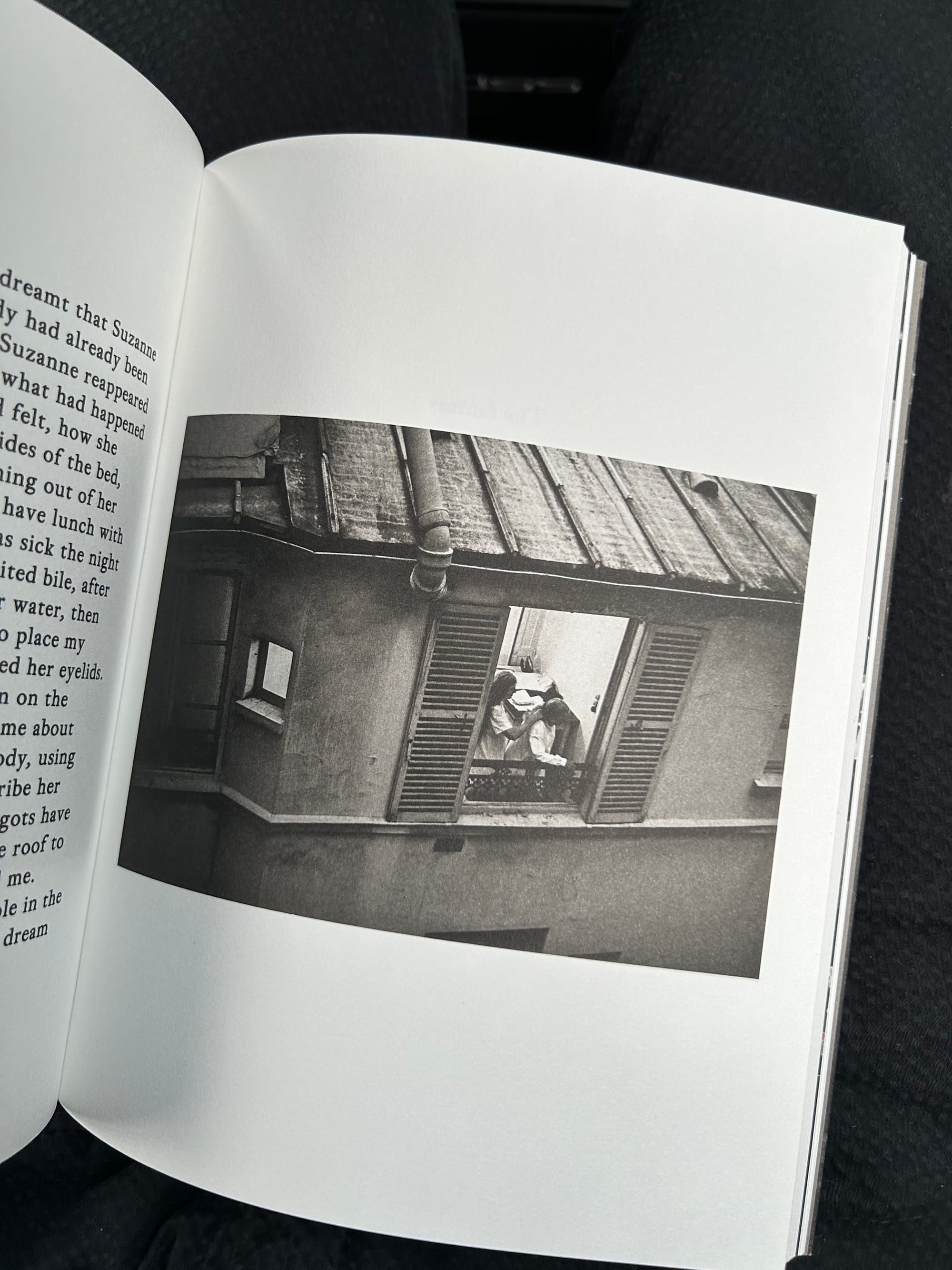

Hervé Guibert (Magic Hour Press)

My car is in the shop so I have an extra hour or so of reading time on the bus. This morning I read, twice, through Hervé Guibert’s photo novel Suzanne and Louise. Guibert has become one of the most important touchpoints for autofiction, and this book I find fascinating for its beautifully skewed take on how an artist might turn family life—his own and, simultaneously, someone else’s—into the material of his work. It’s a weird, weird little story, consisting of 44 black-and-white photographs of his two elderly great-aunts in their Paris home interspersed with snippets of text on their day-to-day lives, how they came to lives such lives, and his process of getting to know them and, indeed, work with them, as they become artistic collaborators.

What emerges, unexpectedly, is a lived theory of photography, not so different from how Roland Barthes’s theory of photography in Camera Lucida emerges from a photograph of his own recently passed mother as a young girl—a photograph Barthes describes but never shares. In his text, Guibert describes his aunts’ approach to their images “as if photography were a sacrificial practice.” In the prologue: “They perform, for him, a dramatization of their relationship.” The young artist participates in an improvisation that becomes a real part of his life. The art is the life, and the life is the art. There’s no distance between them. Guibert published the book at the age of 25; he died of AIDS at 36, which is also my age as I write this.

Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie (Isabella Bortolozzi)

Annie Ernaux, too, has become one of the core reference points of our current strain of autofiction or memoir, though on the opposite end of the spectrum. She lives within memoir, speaking to the truth of experience conveyed through literature. This past weekend marked the close of an exhibition of photographs by Ernaux and Marc Marie at Isabella Bortolozzi in Berlin. Titled “BEDROOM, CHRISTMAS MORNING” after a photograph in the show, it is a simple project of 14 images: over the course of their year-long affair, the lovers photographed the mise-en-scene of the morning after, the state of the room after their liaisons—mostly clothes on the floor in varying states of disarray.

They, too, turned their relationship into an art project, writing short texts to accompany each image that they only shared with each other after the close of the year. A book bringing together their words and photographs has just been published by Fitzcarraldo, though I have yet to read it. The affair coincided with Ernaux going through chemotherapy, a context that shifts ever so slightly the suggestions of touch, of intimacy, that are inherent to these pictures. A superb essay by Jonathan Alexander in the Los Angeles Review of Books looks at both of these recent books in terms of the “theatricality of the quotidian” and the structures for living that they propose. I think that structures like these are some of the most life-giving things that we can learn from artists. Life as a project.

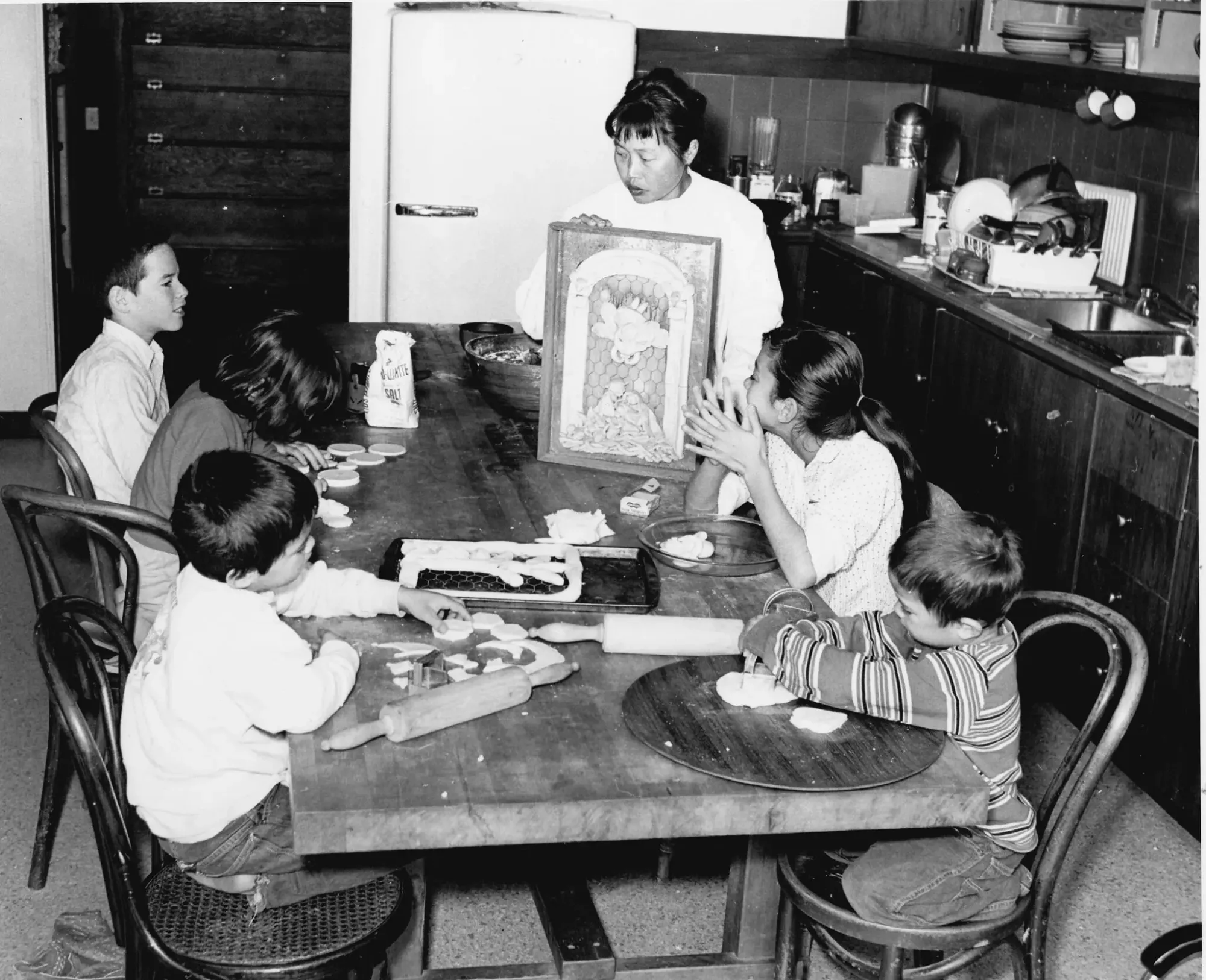

Ruth Asawa (New York Times)

By way of previewing Ruth Asawa’s upcoming retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Hilarie M. Sheets visits the artist’s home in the city. I have to present this without comment:

A lot of times she worked right here,” [Asawa’s youngest child] Paul said, pointing to a discreet hook at the center of a double-wide door frame between the living room and kitchen, where Asawa would hang her looped-wire works in process. “She could sit, or she might have to lie down,” Paul said, as the scale of her curvaceous forms grew, adding that it was a convenient spot to monitor what was cooking for dinner. At the long butcher block kitchen table built by [her husband] Albert, Asawa led group sessions sculpting figures from homemade baker’s clay (a mixture of flour, salt and water), or decorating eggs or making origami by day and family meals by night. “The most important thing to this family was that we sat down to dinner together every single night,” Asawa once told an interviewer. “There were eight of us at the table, plus friends."

There is a new book out by Jordan Troeller that I am dying to read called Ruth Asawa and the Artist-Mother at Midcentury that looks at motherhood “as a means to reimagine the terms of artmaking.”

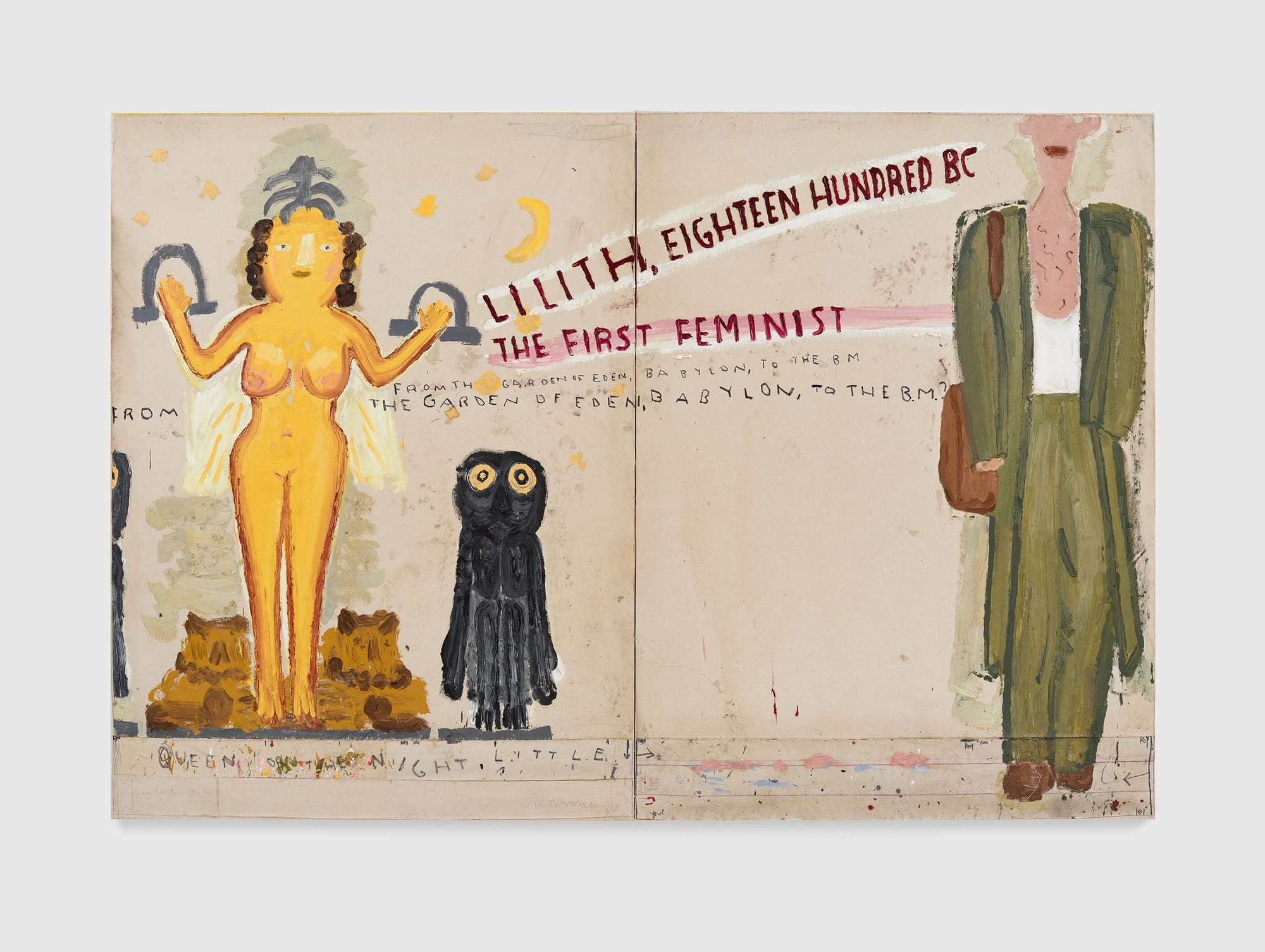

Rose Wylie (Great Women Artists)

Nonagenarian painter Rose Wylie opened an exhibition at David Zwirner in London this week, and promoted it with a series of wonderful studio visits, including an excellent episode of Katy Hessel’s "Great Women Artists" podcast. Born in 1934, Wylie studied art, stepped away from her practice to raise her children, and then returned to the work in her forties newly invigorated and feeling like she had a lot more to bring to it.

I love to hear the stories of how different artists position the work of the home and the work of the studio in relation to each other: for every famously uninvolved mother like Alice Neel or Celia Paul there is a Ruth Asawa building sculpture in the kitchen or a Rose Wylie putting children first. In the podcast Wylie says that she believes that being a mother was an important part of life, and that being a wife was an important part of life. She recalls how her tutors in art school looked down on women who they expected to marry and have children and walk away from art. They were right, she concedes—but not exclusively right. She came back. And, for her, the walking away was not a defeat but part and parcel of the whole thing.

Ed Atkins (Tate Britain)

I can’t wait to see Ed Atkins’s retrospective at the Tate Britain this summer, which by all accounts is an expansive staging of his career. For me Ed is the ultimate poet of the digital self, reflecting back at us how we collapse and inflate ourselves in spaces we can hardly understand with our physical bodies of flesh and blood. Family has become an important part of his work, particularly in the last few years after he became a father—his artist books’ of the post-it note drawings for his daughter’s lunchbox first brought him onto my Nostos radar. But since then, I’ve come to think of this lens as less specifically about artist parenting and more generally about how artists situate their practices within their lives, and Ed’s work on his own parents fill out this picture. Some of his most significant films frame these relationships one by one: The Worm (2021) was a conversation between his own avatar and his mother, focusing on a family history of depression in the depths of the Covid pandemic.

In the new film Nurses Come and Go, but None for Me (2024), an actor reads journal entries that Ed’s father wrote as he was dying of cancer while the artist was in school. In his review, Adrian Searle describes the triangulation of parent, artist, and child:

After the reading is finished Peter and Claire play a game devised by Ed Atkins’ young daughter Hollis Pinky. Peter has now adopted a further persona, and lies on the floor, and Claire, taking the role Ed Atkins used to play in this once-private game, first pretends to be an ambulance, then some sort of doctor, who attempts miracle, fantasy cures for imaginary ills, games of coping and resuscitation, of childhood fears being allayed through play.

Writing on these attempts to “catch the irretrievable moments as they pass,” Laura Cumming says that Ed’s child resists “all this projected significance.” So it goes.

The Guardian loves Ed: Adrian Searle gives him five stars, Laura Cumming only four, and Tim Jonze shares an interview.