Essay

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Essays is an occasional column that teases out in greater depth how family life appears in culture.

It’s something that is repeated often about the occasionally codependent relationships artists have with their work: they couldn’t have lived otherwise. They couldn’t have lived, otherwise. I have no doubt that this is true, that artistic practice plays a constructive or even therapeutic role—that creativity and making and putting something out into the world is one of the things that makes life worth living. But it also seems to be trotted out a bit too often as an excuse for the bad behavior of artists, as if the artistic impulse were in control of their life decisions. This impulse, certainly, is a powerful thing. Over time my interest in what art can do has drifted into the camp of the pro-social, into forms of practice that are inherently social and relational. We want art to shatter our illusions, to break things, to fail spectacularly and in doing so show us the limits of what we are able to imagine, and there are ways for this revolutionary, violent impulse to be channeled into the practice. We have spent a lot of time with Alice Neel, whose two sons had an ambivalent relationship with their mother’s practice and bohemian lifestyle and took their lives in another direction. To conclude this series, I want to turn to the work of Kim Lim, a sculptor a generation or so younger than Neel whose radical work was intertwined with a life of love and cultivation, and whose two sons carry on her legacy both directly and indirectly, continuing to advocate for her profile by shepherding her estate while also developing their own pro-social creative practices. She said of the configuration of their relationship in 1966:

I virtually ceased to be an artist when the children were born and while I felt they needed my full attention. I don’t regret one moment of that time, but since one is now at school, and the other will soon be going, I have returned to art. Of course, it’s different being a woman—but it needn’t be a disadvantage. What one needs is tenacity to keep on working-to sculpture without denying domesticity.

This winter I had the immense pleasure of viewing her retrospective at the National Gallery of Singapore in the company of these two sons, Alex and Johnny, and I have to say there may be no more beautiful way to understand art than listening to brilliant creative minds speaking about another creative mind of which they have intimate knowledge. The retrospective, titled “The Space Between,” was the most comprehensive survey of Kim Lim’s work to date, and faithfully tracked the chronology of her sculpture and printmaking across four distinct chapters from her early wood constructions through her experiments in industrial minimalism to her return to wood and paper and negative space and then to her later poetic work in stone.

Born in Singapore in 1936, she moved to London in 1954 and became one of a small number of women active in the postwar British art world. One of the others, albeit a generation older, was Barbara Hepworth, who as a single mother of three left us one of the best lines about the parallel work of raising children and making art:

I think this idea of a working holiday was established in my mind very early indeed. It made a firm foundation for my working life – and it formed my idea that a woman artist is not deprived by cooking and having children, nor by nursing children with measles (even in triplicate) – one is in fact nourished by this rich life, provided one always does some work each day; even a single half hour, so that the images grow in one's mind.

You see all of these photographs of Kim Lim with her work in the 1960s looking extremely stylish next to her sculptures, the life and the work all of a piece together, completely of their moment and also completely of our moment. It’s easy to imagine how the work found the audience that it has and even easier to imagine everything it had to go through to get here. In one anecdote related by the exhibition timeline, we learned that Lim was the only woman and the only non-white person included in the first Hayward Annual; she was invited to the all-female jury of the second the following year. A figure balanced on a precipice.

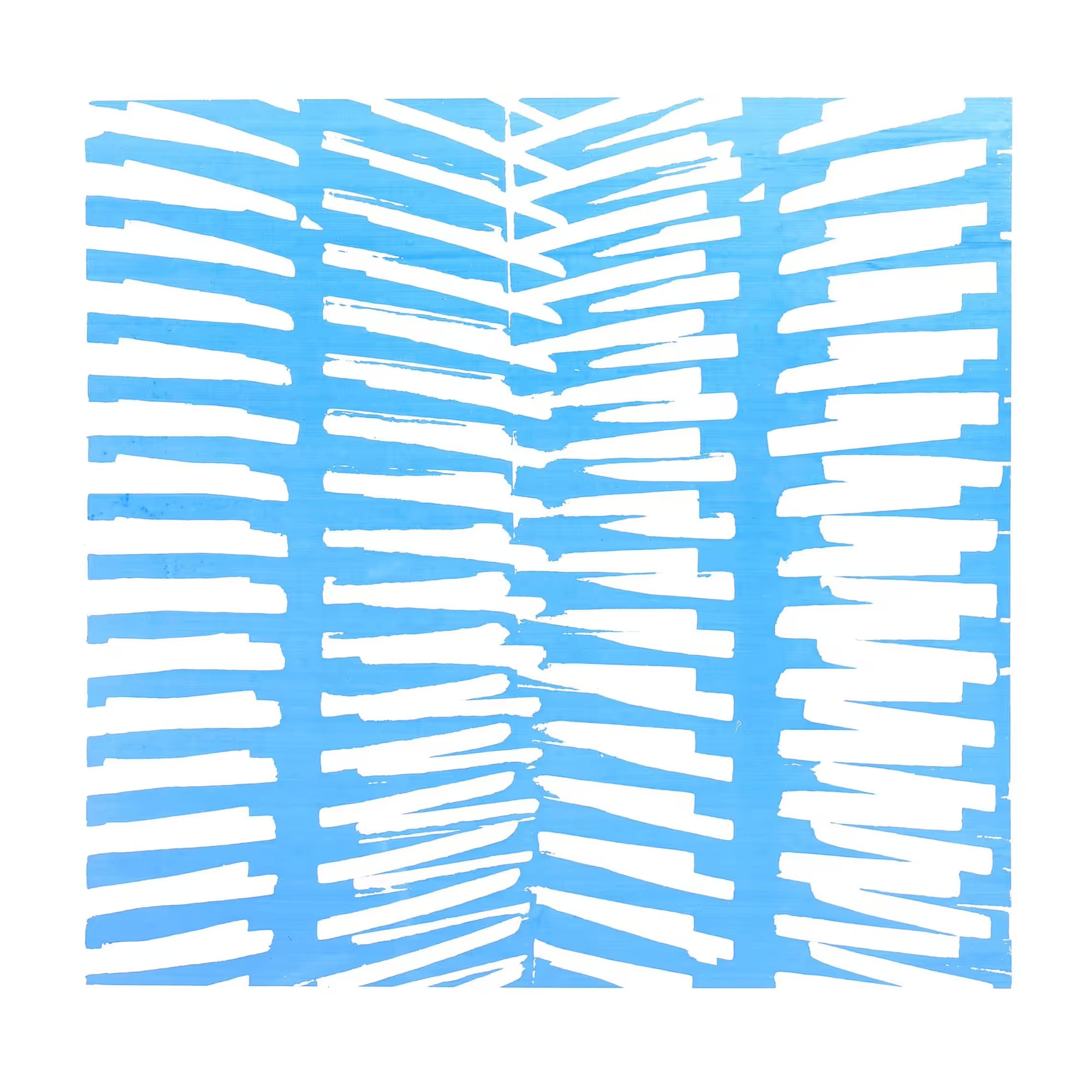

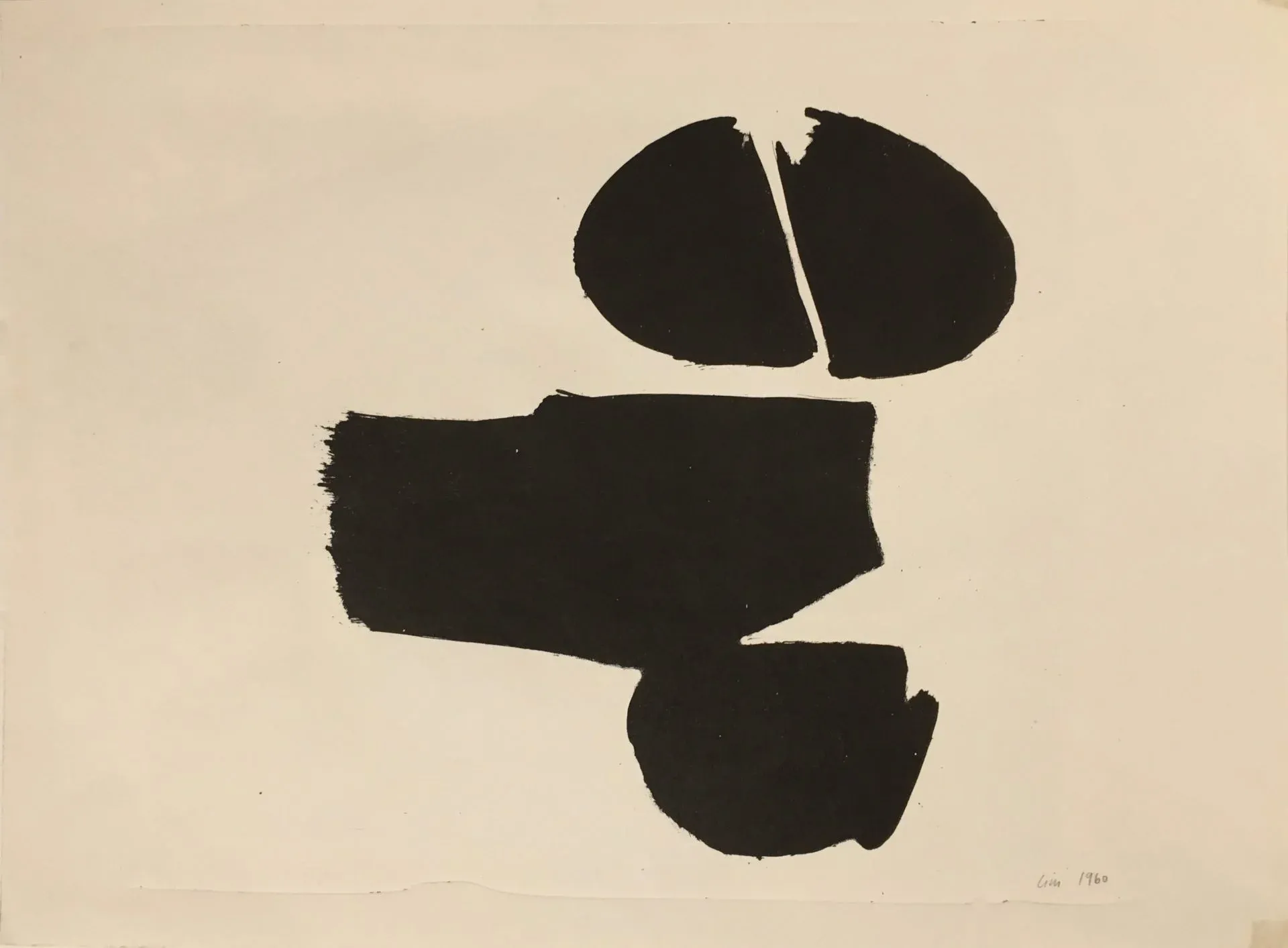

Clockwise from top left: Ronin, 1963; Intervals (Blue), 1972; Sphinx, 1959; Sphinx, 1960. All courtesy of the estate.

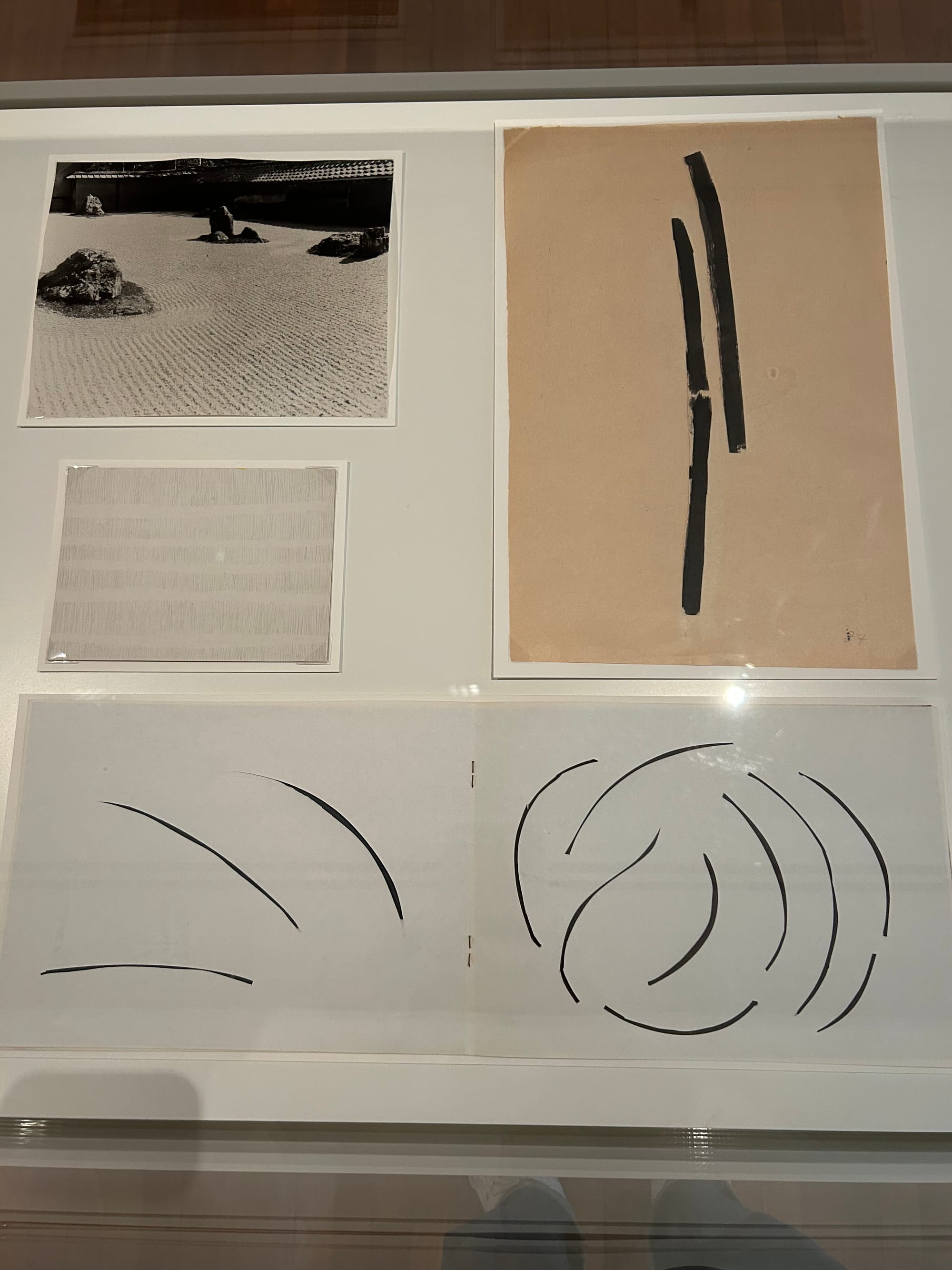

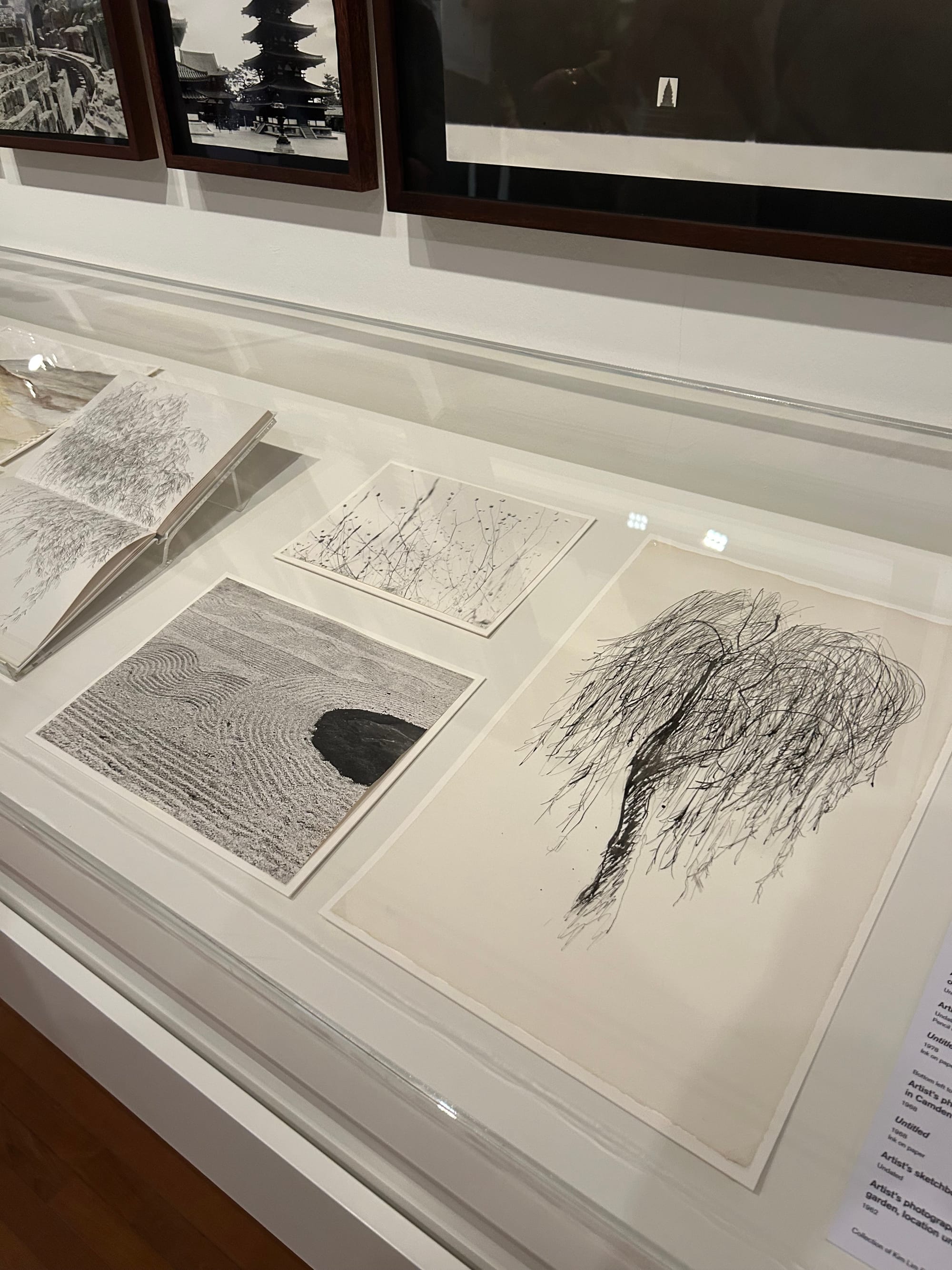

True to the title of the exhibition, some of the most touching moments on our tour of the show came in the spaces in between. The estate contributed a number of maquettes and archival material from the studio, materials that gained a particular resonance through Alex and Johnny’s familiarity. A wall of photographs became one of my favorites. At first glance, they looked like tourist snapshots. Upon closer examination, they revealed themselves as a highly curated collection of formal aspects of archaeological sites and monumental structures, many of which appear as references in Kim Lim’s work—from Stonehenge to Giza to Angkor Wat to Kyoto to the Cyclades. Then, with the added layer of personal narrative, they became a family photo album, opportunities for thinking about and sharing the aesthetic experience within the complex universe of the emotional life of a young family.

Alex and Johnny explained that these were study trips and working holidays, really, something that their parents started before they were born, seeking out direct access to art historical references that could be fruitful for their separate practices. Study trips but also honeymoons; study trips and then also family vacations. Growing up in this environment—and with a working stone carving facility for a backyard—it is no surprise that Alex and Johnny should have engaged with the creative life from a young age. To quote Alex:

There was an incredible respect and love between them [Kim Lim and William Turnbull]. You see in these amazing photos of them when they were young—both striking individuals. There was clearly a physical attraction but also a profound intellectual and artistic connection. They were drawn to each other not just as people but as artists, deeply inspired by each other’s work. Bill always said she was the best artist he knew, and I think he found as much inspiration in her work as she did in his. Though there are intersections in their art, their work remains distinct. … It’s fascinating that my parents came from such different backgrounds—Bill from a shipyard in Dundee and Kim from a well-off family in Singapore. Despite growing up in environments without art, they were somehow put onto this planet to do precisely what they did.

For all of these reasons I have always known that Kim Lim would play an important role in Nostos, but it was only when we arrived at the last chapter of the Singapore retrospective, the rooms about her later work in soft stone, that I started to understand how she would fit into this first essay. Titled “The Weight of Line,” this part of the exhibition draws explicit parallels between her mark-making practices at the foundation of her work with prints and the approach to form that we see in her best-known stone work made after 1979. (I say best-known, but in point of fact the resurgence of museum interest in her work has largely manifested itself in the other lesser-known bodies of work, particularly the wooden constructions, so perhaps this balance has already shifted.) Again the work came to life through Alex and Johnny, who described how their mother would go through cast-off blocks of stone from British quarries looking for a form she could work with, bringing them home to continue muscling them around in the garden. They pointed to a few specific lines that they found particularly weighty, instances of negative space inserted into reality. For me these lines and the phrase, “the weight of line,” called to mind something I have said about my dog’s collar: “the weight of belonging.” It’s a distinctly heavy chain, but she enjoys wearing it—whenever she hears someone pick it up off the counter she trots over and wags her tail and waits for it to be put back around her neck. My theory is that she bears its weight as a reminder of the affection and the mutual responsibility that comes with making a home together.

This weight of line brings us full circle to Alice Neel and Suzanne Valadon, to the distinct mark they share, the heavy dark outlines of their figures, one of the defining visual features of this practice of portraiture—a line that creates a relationship between the viewer and the viewed. In the case of Kim Lim I believe the weighted line holds together her practice across media, from the deep cuts in her stone sculpture to the physical weight of the pressed object that composes her prints. Throughout Lim’s work there is a play of rhythm and repetition, positive and negative space, a work of rocking back and forth to loosen and tighten, as if each time a form is repeated it settles further into a groove and deepens further its line. Art is a practice of discovering gravitas through experimentation.

Both of Kim Lim’s sons are highly creative people who have forged their own idiosyncratic practices and paths through art, music, film, and fashion across Europe and Asia. Alex Turnbull most recently completed the documentary Kim Lim: The Space Between, featuring a soundtrack by his brother Johnny Turnbull. Through this triangulation, they open up for all of us the rich matrix of ideas, forms, and love that they have spent their lives building.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Essays is an occasional column that teases out in greater depth how family life appears in culture.

Towards the end of the Suzanne Valadon exhibition, in the valedictory bit where the museum reminds you which key points you’re meant to take home with you, some objective claims are made about the daring nature of her work. She was, we are told, the first woman to paint a full-frontal male nude (Adam and Eve, 1909). She is Eve, and her lover André Utter is Adam, some 20 years her junior, guiding her hand—or perhaps arresting it?—towards the forbidden fruit. Today we see Adam/André with his genitals covered with a fig leaf belt, a later addition, and we are supplied with a photograph of the original version of the work, a double image of play and propriety. Valadon was also the first woman to paint a large-scale full-frontal nude self-portrait. And, whether or not they were the first to anything, there is something striking and raw and courageous in the way she depicts her body as she ages, as we saw in Part IV of this essay. In the 1931 Autoportrait aux sens nus we looked at last time she would have been 65.

Seeing Valadon at the Pompidou, tracing the thickness of her line and the wrinkles on her faces, brought me back to another visit to the same museum in the fall of 2022, when an Alice Neel retrospective occupied a somewhat smaller, denser space downstairs. Full of stunning pictures, that was probably the exhibition that made Neel contemporary for me, and again was one of the important links in helping me understand portraiture. It had a certain angle: it was particularly interested in Neel’s activism, and in helping the viewer understand that her sitters were not selected at random, not selected on aesthetic grounds. Neel chose who to paint out of a sense of radical social solidarity, an insistence on reflecting back a shape of society as it interested her. It was very much Neel for the high water mark of social practice. Because of how she grasps at these various cross sections of society, Neel’s work now constitutes an archive that lends itself well to such readings at a certain angle. More recently, Hilton Als curated “At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World,” another gathering of characters from her universe that has a lot to teach us about life in the queer family.

When Alice Neel painted her famous Self-Portrait (1980) she was 80, some 15 years older than Valadon in the picture we looked at previously. What is surprising about the Neel is not that she would depict herself in the nude at that age, but rather that she painted herself so rarely, and that it hadn’t happened sooner. The title “self-portrait” appears in her work only one other time, with the Self-Portrait Skull (1958), an ink drawing of a gaunt and leaky skeletal face that forms a stark contrast with the ruddy and very much alive version of herself that Neel actually encountered towards the end of her life.

And while she might not have called them self-portraits, there are a few other paintings that Neel made of herself. We see one in Mother and Child (Alice) (1930) [on the estate's website this one is titled Alice and Her Child]. Even exhibitions of Neel’s early work rarely venture this early; the style is nigh unrecognizable, though still pretty cool looking. At the risk of sliding into the kind of biographical interpretation that we have by now agreed can be simplistic, it is important to understand that she painted herself in a cemetery here because her first-born daughter died at the end of 1927 at less than a year old. Her second daughter, born in 1928, was taken by her then-husband to be raised by his family in Cuba before she was 18 months old. There is another painting, another Mother and Child, this one from 1927, in which the baby’s eyes are open, and there are no tombstones in the background. In her brilliant essay “Futility of Effort: Alice Neel and Motherhood, 1940-46,” Lauren O’Neill-Butler speculates that an even odder painting, Degenerate Madonna (1930), is a “psychological portrait” of this trying time. Her essay is titled after a third 1930 painting of a baby asphyxiated by the bars of its crib.

Until I looked at these paintings, I hadn’t thought too much about Neel’s daughters, rest their souls. I think often about her sons, whose life trajectory seems like a nightmare for the creative parent: one became a “self-described ‘right wing’ investment adviser,” and neither of them had much affection for the bohemian milieu of their childhood. Her grandchildren, fortunately, count among them an abstract painter and a filmmaker, the latter of whom shot a touching documentary that weighs up the rewards and risks of an artist’s life. To be fair, her sons share a respect for her accomplishments, if not a full forgiveness for the price they paid. The arc of history is long.

Neel’s sons come to mind often in large part because she is the first artist analyzed in one of my favorite books, The Baby on the Fire Escape: Creativity, Motherhood, and the Mind-Baby Problem. Already in the title Julie Phillips refers to an anecdote from Alice Neel’s life: Isabetta, the daughter who was taken to live with Neel’s in-laws, was later told that Neel had left her on a fire escape while she was painting. As with This Dark Country, I have learned a lot from this group biography about the limits and possibilities of writing about the artist’s work and the artist’s life side by side (“her awareness of parental entanglements often gets into her portraits”). For the most part, Phillips writes about writers: Doris Lessing, Ursula K. Le Guin, Audre Lorder, Alice Walker, Angela Carter. Neel is an exception, and this is perhaps what makes her case particularly compelling. Across these figures we read about different approaches to love and romance, to the labor of child-rearing, to domestic responsibilities, to creative labor, to gender in general. There are no answers, no conclusions, no one right way to do things. In the end, there is only the way things happened. Ginny Neel, who married Alice Neel’s youngest son, says that Alice “became famous … so it was worth it. Just the slightest twist and she could have never been much heard of. And then what, it wouldn’t have been worth it?” Towards the end of her life, Alice herself answered. “What will they think of me afterwards? You know, I had to do this. I couldn’t have lived, otherwise.”

On that 2022 trip to Paris, when Alice Neel was showing on the mezzanine floor, I attended a cocktail back upstairs hosted by Chanel’s Yana Peel for the rededication of a terrace in memory of the recently passed architect of the building, Richard Rogers. During the ceremony Ruthie Rogers gave a moving speech in which she recalled a conversation they had in their Paris years, where they lived during the construction of the Pompidou. She remembered that they had stopped at a cafe late in the evening, she in her 20s and he in his early 40s, and they were watching an older couple on a night out at an adjacent table, and he projected forward a future idyll: to be elderly, in love, and fully alive—in Paris. Paris represented something for them, a way of living that would have consequences for our understanding of how a city should work. I often listen to Ruthie’s Table 4, a charming podcast in which the host talks over her famous guests indiscriminately and retells their stories as her own, as all good storytellers do. Recently she had on Bella Freud, and they reminisced over Lucien Freud’s midday drives from Soho to the River Cafe. I love these stories, generation to generation, splintered family to familiar splinter. Bella Freud has her own equally charming podcast called Fashion Neurosis.

What a thing to imagine the early 1930s, this moment of overlap that materializes across the floors of the Pompidou: an aging Suzanne Valadon facing the mirror topless in Montmartre, her grown son by then also an artist, while in Greenwich Village a bereft Alice Neel painted through the loss of her two first children, not yet settled into her neighborhood, her apartment, her practice—not yet settled into the language that would become her own. She had to find her way there. She couldn’t have lived, otherwise.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Essays is an occasional column that teases out in greater depth how family life appears in culture.

Earlier this winter I was lucky to catch the retrospective of Suzanne Valadon at the Centre Pompidou on what I imagine will be my last visit to that museum until it reopens in 2030, god willing. It was a rare personal trip to Paris outside of my annual fall pilgrimage for the art fairs. This time it was romance that brought me there, a fact that everyone I told almost uniformly agreed was the best reason to visit their city. So I was in a certain state of mind as I stored my dripping umbrella and made my way up through the escalator tubes to the special exhibition galleries, making my way between the spaces of the in-between, endings and beginnings, hellos and goodbyes and all of that. I had never heard of Suzanne Valadon and had no idea what to expect, other than it came highly recommended, but there is a certain freshness to seeing something in the right company, in holding one’s eyes open out of curiosity and hope, and I was rewarded immediately. From the opening salvo of the exhibition, Suzanne’s paintings assert themselves with the immediacy of gestural brushwork and an imposing weight of meaning and consequence.

Although I am no expert, assuming that some readers will be as unfamiliar with her work as I was, I will share a brief biographical sketch: Suzanne was born Marie-Clémentine Valadon in 1865 to a single washerwoman in Montmartre, and came into contact with art when she began modeling (among other odd jobs) at the age of 15 for Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who gave her her nickname—after the biblical Susanna. She also drew, and received encouragement from Toulouse-Lautrec and Degas. Becoming a single mother herself at the age of 18, she continued living with her mother, and developed a practice of portraiture based on her mother and son, as well as lovers and friends from a wider circle as she rose in social status through the reception of her work.

It should be clear from this description alone how Suzanne’s work fits into the story I have been telling about how the life of the family fits into and alongside the life of the artist. With Adam et Eve (1909) she became, some say, the first woman to paint a full-frontal male nude; her new husband guides her hand towards the forbidden fruit. Portraits de famille (1912) pictures her surrounded by her mother (whose face is deeply scarred with wrinkles here and nearly everywhere she appears), her son (dreamy and erect), and her second husband (resigned; at peace). One of my favorite pairings in the exhibition captures the arc of childhood: Marie Coca et sa fille Gilberte (1913) finds Suzanne’s grandniece with a doll on her lap, leaning against her mother’s legs. Later, in La Poupée Délaissée (1921), the girl is grown, turning away from her mother and absorbed in her own reflection in a handheld mirror. The titular doll—the same one from eight years earlier—rests on the floor. Suzanne had a special love for mirrors, both handheld and wall-mounted, and for boudoir scenes, and in particular for the twisting and stepping poses of getting into and out of the bath. (See La Petite Fille au miroir, 1909.) She is, I believe, the patron saint of the rear three-quarter-angle nude.

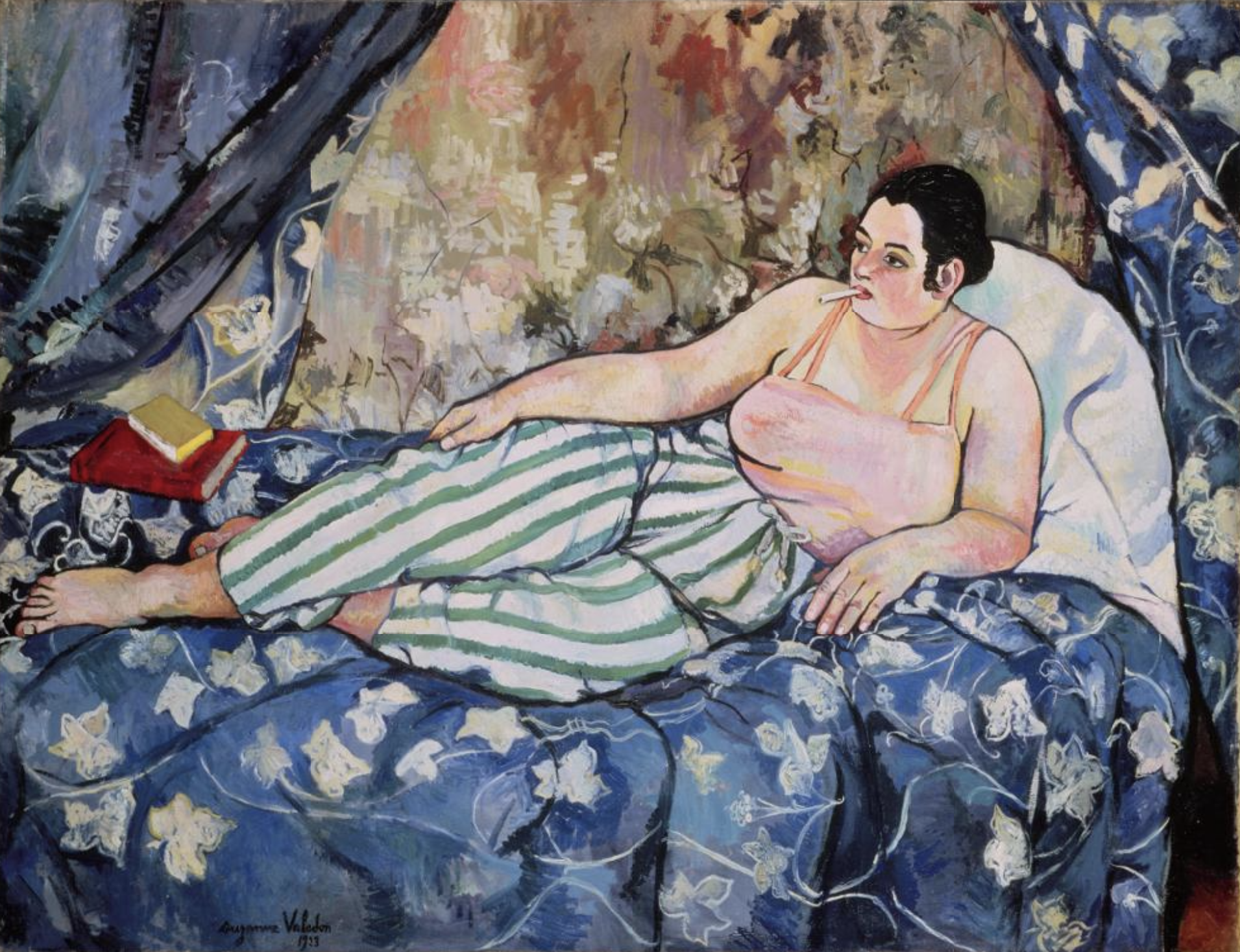

Suzanne made what I consider her best paintings in her fifties and sixties, in the two decades prior to her death in 1938. The Pompidou exhibition opens with La Chambre bleue (1923), one of several pictures that are so stupidly brilliant that they could pull the wall straight down into the floor. A heavyset woman in a pink camisole and striped green pajama pants rests on one elbow, books at hand, an unlit cigarette between her lips. The bedspread is Matisse and the wall behind is Joan Mitchell. From the same year, Catherine nue allongée sur une peau de panthère (1923) has a reclining nude on a leopard skin over a rug, pink poppies in a blue glass vase perched perilously close to languorously draped fingers. The rainbow skin of this buttock slam in the center of the frame—it contains the universe.

In a series of self-portraits made when she was 62 or 63, Suzanne depicts herself in what I can only describe as the harsh light of loving self-acceptance. She has none of the luscious skin finish of her nudes, and none of the cinematic airs of some of her other portraits. She is not young, but she is not old—at least she has far fewer wrinkles than she gave to her mother earlier in her career. My favorite is Autoportrait aux sens nus (1931). At this point she has been painting herself in the nude for decades, and yet it can’t have been common for a woman of her age to look back at the viewer so defiantly dignified, so much a part of herself. In the way she handles the skin of her left shoulder, partially in the shadow of her face, I see something of Celia Paul’s palette. And, of course, this brings us to Alice Neel.

I am hardly the first to notice the shared sensibilities between Suzanne Valadon and Alice Neel. First and foremost, the thickness of line with which they both tend to outline the bodies of their sitters; it is visually striking and makes for a unique conversation across time between these two women. And of course, the empathy for affect and feeling in the body of the sitter, particularly in the seated domestic interior portraits that form such a significant portion of both of their work. If there is one significant point of departure, however, it is in Suzanne’s sumptuous attention to the textures and patterns of her interiors. In Alice’s pictures, everything beyond the person—sometimes everything beyond the face, even everything beyond the eyes—fades into irrelevance. For Suzanne, a person must be situated: placed within the context of their costume, of the furniture, of the room. We see the same couch, the same throw in many pieces, and we see her own environments shifting and evolving over time. Where Alice pushes back at the encroaching domestic sphere (a topic I will turn to in the next part of this essay), Suzanne indulges it in all its messiness and improprieties, painting a universe perfectly parallel to the escaping tulips of Dora Carrington’s still life.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Essays is an occasional column that teases out in greater depth how family life appears in culture.

Portraiture for me has become a practice of autofiction. When I started my career, I was obsessed with technology and bored by painting. I was undereducated and under-informed, and have only learned a little bit since then. A lot of my writing and thinking in the first decade of my career was on what we called post-internet art, which Karen Archey and I defined as contemporary art “consciously created in a milieu that assumes the centrality of the network.” A key point of reference for us was David Joselit’s idea of painting beside itself; I remember Karen telling me about a dream in which she titled an exhibition “Everything Beside Itself.” Up to a certain moment, the only painting that made sense to me was conceptual in nature, playing with the codes of digital culture to make painting about its own production. Following David: Jutta Koether, Wade Guyton, Seth Price. Serious and impersonal painting.

Through approaches to portraiture like Celia Paul’s, I have slowly come to understand how every painting stands beside itself, how the social diagram of the production of art is actually visualized in many kinds of painting, if not most, and acknowledging this reality is, in fact, one of the primary directives of looking at and talking about art. In her current exhibition in London, Celia recomposes a famously staged photograph of Lucien Freud, Frank Auerbach, Francis Bacon, and Michael Andrews out to lunch in Soho in 1963. This is not a biographical anecdote. This is painting fully beside itself. There is zero distance between Celia’s Colony of Ghosts and Jana Euler’s “GWF (Great White Fear)” paintings.

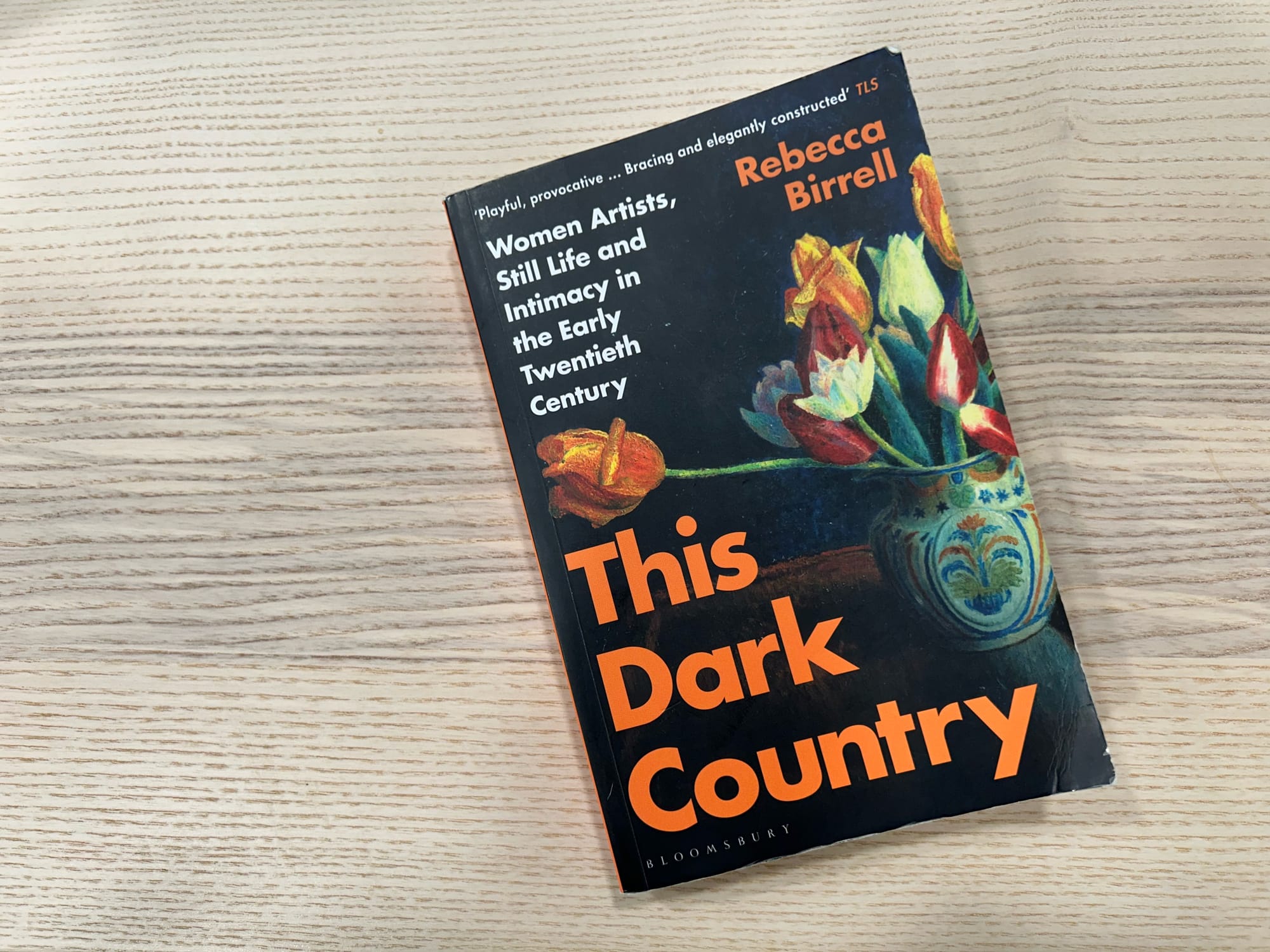

At the London Review Bookstore a few years back I picked up a copy of This Dark Country, a striking book by the curator and scholar Rebecca Birrell that has become enormously important to me. Subtitled Women Artists, Still Life and Intimacy in the Early Twentieth Century, it is something of a group biography of Bloomsbury, and a project of criticism that invigorates still life as a visual key to the interpretation of the domestic lives of the artists. One might call it still life beside itself, or the domestic interior for the age of metadata. The basic observation is unassailable: these artists were living and working in unusual and radical domestic configurations, and so the visual environments pictured in their work bridge the practice itself with the life around it. Another way of describing the modernist mode.

In This Dark Country, Rebecca’s observations are always striking. Often they are elucidating; sometimes they seem to be reaching, and yet when they are reaching they are also at their most creative. She calls her form of close reading “overreading,” after Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, and says she is “more interested in possibility than proof.” This, I think, is where the creative possibilities of criticism come into play, where criticism can be more than biography, and where the reading of a critic might open up new windows into the work, and for the work into the world. And this, after all, is why we write criticism to begin with.

On the cover is a detail from the Dora Carrington painting Tulips in a Staffordshire Jug (1921), in which Rebecca identifies two tulips “attempting to distance themselves from the rest of the bouquet,” leaving behind “intimations of disappointment, need and discord.” She goes on to connect the composition to her lover Ralph Partridge and the triangulation of their relationship within Bloomsbury. As a reader, you have to learn a lot about the biography before you can begin to see anything in the paintings other than genre and technique. In my generation we are sadly inured to the spiritual life of a still life with flowers.

Studying theory and criticism in college, we learned to be suspicious of the biographical fallacy, of the idea that the narrative of an artist’s life might help us understand his or her work in any meaningful way. We should start from the work itself, we learned, and from its reception in the world, and never take the original artifact as illustrative of an external reality. For the past 25 years, literature has been so dominated by autofiction that it has become as natural as breathing. This is not the case in contemporary art. Despite diversions into things like new sincerity and identity art, art has largely tried to preserve a further layer of mediation, even distance—to cling to the position of the critic rather than the artist.

Anna Kornbluh would disagree: in her book Immediacy she argues that the immersive installation as a medium is cut from the same cloth as social media and memoir. I counter that immersive experiences are far enough from the central thrust of what artists are actually doing to undercut this line of thinking. I also wonder if the act of interpretation that Kornbluh wants to see happening, the work of critical engagement, might actually be taking place immanent to the surely self-conscious authorship of much of this culture supposedly opposed to mediation.

Frances Lindemann, writing in The Drift, takes inventory of autocriticism in the literary field: Emily Van Duyne on Sylvia Plath, Rebecca Mead on George Eliot, Jenn Shapland on Carson McCullers, Joanna Biggs on nine women writers. She describes the problem:

Three distinct but related types of identification are at play in this genre, which we might call auto-criticism: the author’s personal identification with a character, her identification with the writer at hand, and her identification of that writer’s life with her work. (This last type is also known as biographical criticism.)

Rebecca Birrell’s biography of Bloomsbury does not reach into memoir, other than in brief asides that mention her research in the first person, but I almost wonder if that might further enrich it. Rather than trying to get rid of mediation, this winking inclusion of the author for me can celebrate the relational nature of the twinned acts of writing and reading. Frances concludes her argument:

Auto-criticism, and its identificatory principle in particular, is most fundamentally flawed in its false understanding of the directionality of reading.

When we willfully misread art or literature, we accept that we are seeing our reflection in the glass along with whatever we are looking at. We recognize that we cannot possibly imagine ourselves in the exact circumstances of the artist—and that we would not want to even if we could, because the whole point of art is to somehow speak across time, across subjectivities, from your universe into mine. Reading is a multi-dimensional practice. We create new dimensions with every reading. When we peer through a frame and into another plane of being we see an act of imagination tied to a real person in a real place and time, and we—real too in our own place and time—must commit another act of imagination. And this makes it no less real. It resonates back and forth, sometimes forever.

What I have learned from Rebecca Birrell is that there are interesting things to learn out there, and archival research plus a trained eye can unearth stories that enrich our readings of art. This is a creative act, and the stories that resonate with us have as much to do with us as they do with the artists.

My mother is visiting Taipei this week and while we were browsing moom bookshop I picked up a copy of The Bloomsbury Cookbook. She is here to spend a couple days with me after a week looking after my daughter while I was away on business at the art fair in Hong Kong. Paging through recipes from Charleston as we recover from a meal of oden and Czech wine, the importance of domesticity, of cooking and eating together, of a good interior, of a communal energy could not be more obvious. In the case of Bloomsbury, the radical impulse comes right up against the domestic appetite, and they are seen to live not in opposition but in harmony, bound up together. I am learning to see in a still life with tulips the whole world we are trying to build around us. I am learning to map it out in an omelette and a loaf of bread.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Essays is an occasional column that teases out in greater depth how family life appears in culture.

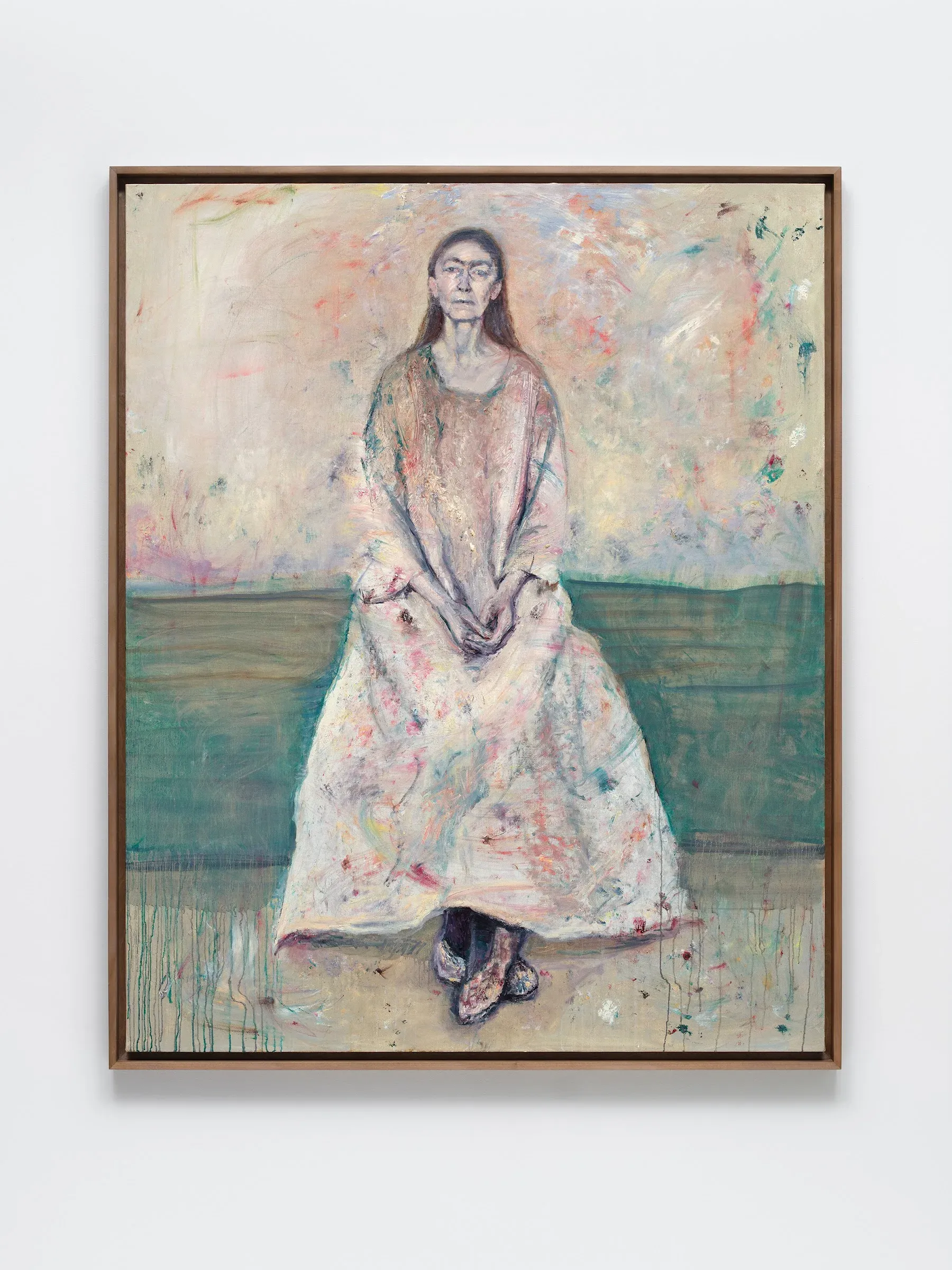

Karl Ove Knausgaard’s profile of Celia Paul, like most of the press she gets, leads with a visit to her flat in London. Based on the descriptions that her interlocutors and interviewers share, it sounds like a theatrically sparse place, a minimally viable configuration of chairs and bed frames that provides just enough surfaces to sit on and gaze into the mid-distance, just enough windows through which to notice a corner of a roof or the branch of a tree, and just enough bare walls against which to lean paintings. Just enough of a space, in other words, for one to focus on the twin projects of looking and being looked at, which she has made the core of her blessedly old-fashioned practice as a painter—a painter of the sort who paints the things in front of her. Knausgaard writes of how he understands her work:

… their distinctive combination of weightlessness and heaviness. The physical, material world that they depicted seemed light in some peculiar way, while their emotional presence was always heavy: the paintings were grounded in feelings. Usually it is the other way around, isn’t it, the material world has weight, and the inner, the spiritual, the abstract are light, and ungraspable, really.

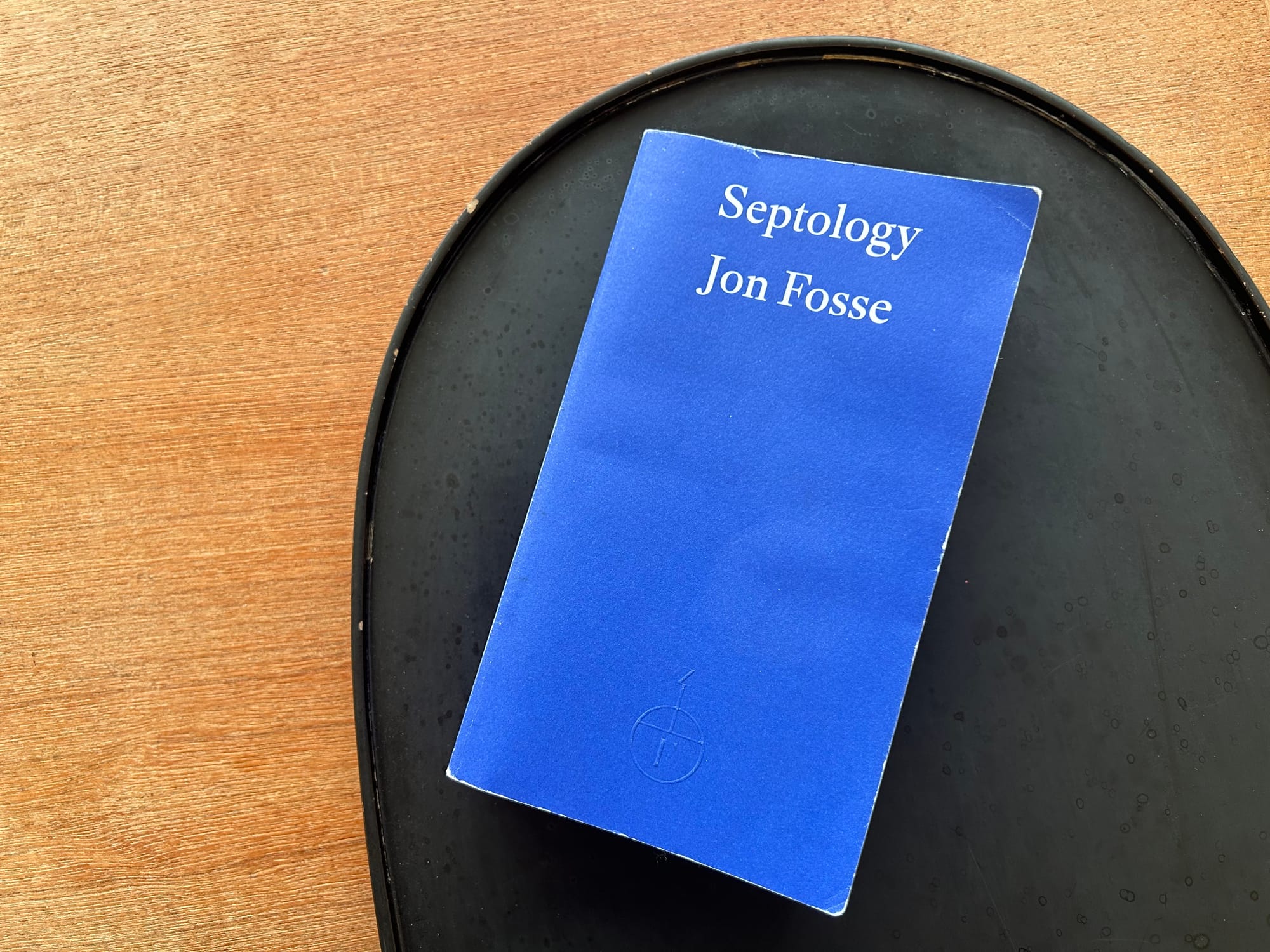

And he might as well be speaking the language of Asle, of the “luminous darkness” that our fictional artist seeks in his paintings. When Jon Fosse (speaking through Asle) writes of how it is only at the darkest moments “when the darkness starts to shine,” this is not only a metaphor for finding the grace of forgiveness and acceptances when the going gets tough; this is very literally how Asle is making his compositions, turning his lights off and looking at them in the gloom of the Arctic dusk, looking for a strength and brightness that he puts onto canvas through overpainting and underpainting. Through the materiality of the painting, Asle incorporates the spiritual sense of the ineffable into landscapes, moments, and portraits. This is what Knausgaard is suggesting here: it’s the light that’s heavy. He comments specifically on Celia Paul’s series of paintings of chairs. She explains herself:

I think my chair paintings are self-portraits. I have two identical chairs: one is in my studio—my models sit on it—and this one, the one that I paint, is in the room where I sleep.

Knausgaard on the same chair paintings:

We see not the chair in itself, as that is for sitting on, but the moment it represents, the here and now it lifts forth. Not the world, but our connection to the world. … Shouldn’t someone have been sitting in that chair? In a strange way, the absence of a person reveals another presence, for, though the room is certainly empty, it vibrates with life, and it does so because someone sees it, and that someone exists in the painting, in its colors and shapes.”

Immediately I think of the twin chairs of Septology, one for Asle and one for his late wife, the presence who haunts his home studio and all corners of his life. She, too, was a painter, though as his career progressed and hers stalled she turned inward and focused on icon painting. We cannot tell if she became a contemporary artist interested in icons or if it was purely a hobby so, although she didn’t seem to exhibit widely, I choose to again hold this contradiction loosely and think of her icons as doing what Asle’s paintings do, reflecting back the light in the darkness.

Asle is a rugged individualist of an artist. Though he begrudgingly accepts the companionship of his neighbor and his namesake, his time in the studio is pure solitude. By way of company, he sits and fixes his gaze on a specific portion of the sea. The other chair must remain empty. Celia Paul’s practice, on the other hand, is a profoundly social one. Her work is all about connection. Across the decades, she paints her mother, her sisters, her son, her lover and his friends—all in the same chair, within the same four walls. Her connections to these people matter. That chair glows with the presence of a life lived to the fullest. Knausgaard:

It is easy to think art that leans toward the autobiographical is first and foremost a representation of things or events. But the essential fact about art is that it is an event in itself. It is something that comes into being.

Celia Paul’s Bloomsbury studio, where she has lived since 1982, was a gift from Lucien Freud, her lover, tutor, and portraitist. The space itself, the framework, the walls that surround the chairs, are a part of the practice of living, of loving, of modeling, of painting that she constructed in relationship to him. She has spoken openly of how her work found a new dimension of freedom after he died. Much has been said about their relationship, the degree to which it defines or does not define her work, the extent to which it was positive or healthy or anything else. I’m not sure much of that matters, in that it’s less about that particular relationship and more about the fact of relationship, the field of social connection in which she has chosen to pursue her painting. This is what makes her work so very much of our time. Now in her 60s, Celia has become known for her writing in addition to her painting, and she speaks eloquently on the back-and-forth between these two ways of working:

It is a way of articulating thoughts that otherwise just brew. That can work evocatively in painting. But with words, you need to have order of a different kind. One sentence does have to follow another.

It was her memoir Self-Portrait and the more recent Letters to Gwen John that opened my eyes to the field of connection that underlies her painting practice. Letters, in particular, I find one of the most beautiful meditations there is on how we understand art as a part of life, on how art draws from life and in return gives a sense of shape back to it. In Gwen John, Celia sees a parallel life from another pocket in time—a namesake who lived nearly a century before her.

Like Celia, Gwen John studied at the Slade. Like Celia, Gwen John entered into a relationship with an older artist, and their affair became a defining aspect of how she related to art and to the world. In Celia’s letters, we get a sense of how she goes about her day to day, how she thinks about her paintings, but we also get to look at Gwen John’s work, and at Rodin and their milieu, with fresh eyes. Gwen John’s portraits, particularly her self-portraits, printed alongside Celia Paul’s, are revelatory—modern. And yet:

Gwen never tried to paint Rodin and she made no pencil sketches of him. He was her ‘Maitre’ and she was so overwhelmed by him that she wouldn’t have been able to work from him. … She wanted Rodin to look at her, but she didn’t feel able to return his gaze.

In her newest body of work, Celia’s paintings have taken on something of the religious icon for me, as much as they have also absorbed the social portraiture of Freud. In the press release for the new exhibition, “Colony of Ghosts,” her practice is described as “looping back and forth through time to the people and places closest to her. … Constancy and change, and how the past is always held in dialogue with the eternal present of the painted image, are, for Paul, inextricably linked to a consideration of self.” We see in these images a field of space-time that is turned into light, a living and breathing field of life that comes through every object, every surface, every wrinkle on every face, every knuckle on every hand. Reaching into her own past, like Asle:

My young self and I—we are the same person. I can stretch out my old hand—with its age spots—and hold my young unblemished hand.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about the intersection of art and life. Essays is an occasional column that teases out in greater depth how family life appears in culture.

When you finish reading a book like Septology, the impulse is to reach out immediately: to cast about on the internet, to message friends, to wedge it into conversations, to write something down, to figure out what’s sticking in your mind and then compare notes to understand if your experience of the book is coming from inside the book itself or from mythical status of the book.

From what I can tell of my casting about, most people think that Septology is about god. Asle, the aging painter who narrates the novel in his stream of consciousness, falls asleep each night—closing each of the seven volumes of the story—somewhere in the process of moving along his rosary beads, either in the Lord’s Prayer or Salve Regina or Ave Maria or one of those other bits of sacred ritual that have been sadly abandoned in the churches that I grew up in. When he speaks about god, however, he is very clear that he doesn’t believe in god at all, at least not in the traditional “old-man-in-the-sky” conception of god. Asle feels the presence of god in two places: in the love and connection he cultivated with his late wife, and in the creative process of painting that he has spent a lifetime pursuing. To quote William Blake:

Every thing that lives is holy.

Septology contains some of the best descriptions I’ve read of how art functions in the life and mind of the artist. Not all artists, of course, but some of them, and particularly those who remain committed to the modernist idea of art that spans the long twentieth century, bound up with the practice of calling a self into being. With all of the connections between light and the divine that Jon Fosse weaves through his writing on painting, particularly the “luminous darkness,” at a certain point in my reading I started picturing Asle’s work in the key of Celia Paul. Until I started reading her writing, I did not get her work at all. I lacked the capacity to understand not only her work, but probably an entire strand of contemporary art (this same one that I refer to here, the one committed to or at least growing out of the modernist idea of art: individual and spiritual and craftsmanlike, bookended between an earlier institutional aesthetics of ritual, what modernism struggled against, and a later institutional aesthetics of bureaucracy, which art has become). I could not have read Septology without having first read Celia Paul.

Partway through Septology, I was shocked and gratified to see that Karl Ove Knausgaard, whose blurb sits prominently on the back of my thick Fitzcarraldo edition of the book (“Jon Fosse is a major European writer”), had authored a new essay on Celia Paul, published in the New Yorker and in a MACK monograph to accompany her forthcoming Victoria Miro solo exhibition. Shocked because I did not expect such a literal connection to be manifested into reality, at least not so quickly; gratified because it always feels so predictably good to have my intuitions confirmed or at least paralleled by minds much greater than mine; and then also maybe a little bit mortified, because the timing was all a little bit too perfect, and I wondered if I had perhaps seen a reference to this forthcoming essay and somehow started visualizing Celia’s paintings within Asle’s narrative.

Septology is about the multiverse. Asle seems like a thoroughly wholesome widower, still married in deed and mind to the late love of his life: when his neighbor sits down in her chair, untouched these ten years, his reaction is visceral. As he drives between his home and the city, where he buys groceries and art supplies and delivers paintings once a year to his gallery, he continually encounters phantom versions of himself. He sees himself young and falling in puppy love with his wife; he sees the two of them moving into their first home outside the city (they too, in nested flashback, notice his car driving by). But he also encounters another version of himself, not these shadows of his own past but a present-day alternate reality self, another painter named Asle drinking himself to death. We learn that the two Asles met when they were still teenagers, and have gone through life aware of one another, as the wholesome Asle moves from triumph to triumph in his career and in his marriage, while the shadow Asle suffers through the dissolution of marriages entered too easily, the instability of finances never given a chance to get going, and ultimately the lonely descent into drinking the dark days away.

The beauty of first-person narrative, the beauty of this way of telling so many different stories at once, is that we as readers have profound access to the protagonist Asle’s painting. He starts every morning considering the canvas that he is working on, a purple line and a brown line intersecting to form a cross, and we learn about where his paintings come from, how he started painting pastoral scenes from his rural village and then quickly learned to paint out of his mind particular images or moments that stuck with him in his observations of the everyday. He narrates at length the way that light shapes his process: “the pictures I paint in spring and summer have to wait until autumn or winter before I can really see them, yes, in the darkness, yes, I need to see pictures in the dark to see if they shine, and to make them shine more, or better, or truer, or however it’s possible to say it, anyway the picture has to have the shining darkness in it.” Then, when he paints a portrait, which he does rarely—one portrait of his wife sits leaning against a chair in his attic; he also paints his neighbor’s sister sight unseen as a Christmas present—we see Celia Paul. I am incapable of imagining these pictures as anything else. They sit so clearly in my mind that I fear their dark luminosity will be burned into my eyelids.

And yet, a bit weirdly, we have no conception of what the other Asle’s paintings might look like. We read about his work only during the time when light Asle and dark Asle first meet: dark Asle is living in a basement and sleeping with a pub waitress, and they are introduced by a mutual drinking buddy. They bond over a mutual resistance to painting the kinds of anodyne pastoral scenes that people from their villages are willing to buy. This is all we learn of dark Asle’s work; it is like he represents an arrested development in the process of artistic growth. Light Asle has already started moving on, but dark Asle feels bound by circumstance to keep churning them out: he sells his pictures for beer money on the steps of the pub. And yet, it is dark Asle who is first accepted to art school, and dark Asle who implicitly gives light Asle permission to leave high school early to pursue this track. We never see dark Asle’s work again.

A lot of doubling and doppelganging is happening in culture right now. In both Severance and The Substance, the public self and the private self struggle over agency. We share one body and, perhaps, one soul, but choice and chance conspire to create circumstances that splinter our realities. The work of love is the work of reconciliation. You are one. God is in the darkness:

It’s in the hopelessness and despair, in the darkness, that God is closest to us, but how it happens, how the light I get clearly into the picture gets there, that I don’t know, and how it comes to be at all, that I don’t understand … it’s definitely true that it’s just when things are darkest, blackest, that you see the light, that’s when this light can be seen, when the darkness is shining, yes, and it has always been like that in my life at least, when it’s darkest is when the light appears, when the darkness starts to shine, and maybe it’s the same way in the pictures I paint, anyway I hope it is

Septology is not a morality tale. Hero Asle and shadow Asle are not two choices that a person can make—righteous choices do not lead to mystically good ends, and dissolute choices do not drag one down into despair. The two Asles are one and the same, fundamentally and inextricably bound together. How this works within the universe of the book, I have no idea. I choose to read it at a distance, to allow these paths and routes to wrap around one another and intersect as they choose. As a reader, I hold this contradiction loosely, like the composition of the painting that opens each chapter:

two lines that cross in the middle, one brown and one purple, and I see that I’ve painted the lines slowly, with a lot of thick oil paint, and the paint has run, and where the brown and purple lines cross the colours have blended beautifully and I think that I can’t look at this picture any more