Projections

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Projections is a regular column on films that touch on living in a creative family.

We tend to look on with something less than generosity when people make art too directly or too biographically about members of their family. Earlier this week Kaitlin Phillips described Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold as “pure hagiography by an underemployed nephew.” (I don’t know Griffin Dunne as a director, but he played an excellent Sylvere Lotringer in I Love Dick and I’m only slightly embarrassed to say I spent an inordinate amount of time with him in This Is Us.) Perhaps we should not expect critical engagement with the work from these kinds of projects. What we watch for instead is the anecdote of intimacy, the tendency of the lesser-known relative to share trivial moments of family life—celebrities have them, intellectual giants have them—in a way that somehow illuminates our own reading of their work. Our relationship with the work, after all, is our own. The work does not belong to us, the person certainly does not belong to us, but the way it lives with us, the experience it creates in our lives—that belongs to us and to us alone.

Tomas Koolhaas shot REM (2016) over the course of three years during which he followed his father through the far-flung offices of OMA, onto construction sites and into completed projects, and to the opening of the Venice Biennale the year that Rem curated it. Kaitlin’s criticism holds here, too: what we see is pretty anodyne. It can’t be easy to shoot your father the way you see him, the way you want to see him, the way he wants you to see him, the way you want him to see you seeing him, and the way he wants the world to see him all at the same time. As viewers, we get some well-considered quotes on architecture and urbanism from a great designer looking back on his career and beginning to think about the end of an era. He looks at the grand sweep of OMA over 50 years from New York to China and now to the Middle East, with Europe inevitably as a home base that acts as foil to whatever else he is working on. He describes his practice as a willingness to engage with impure things and look for the rigor within them.

In the opening shot, young people skateboard in front of Casa da Música in Porto, where my father lives. The building is perhaps more iconic as a skate spot than as a music venue. Later on in the documentary, intertitles will relate: “A building has at least two lives—the one imagined by its maker and the life it lives afterward—and they are never the same.” Like a child, a building has to live out its own independent life. This becomes increasingly evident as Rem and Tomas visit completed OMA buildings: they interview the unhoused about the formal qualities of the Seattle Central Library, then meet with the daughter of Jean-François Lemoine, the late publisher for whom the Maison à Bordeaux was originally designed. Full of custom mechanisms to enable the partially paralyzed man to live an active life, the house is a bit ghostly without him to activate it; we watch Rem stare into space as he moves up and down on mechanized platforms while doors open and close around him. The challenge, says the daughter Lemoine, is to give new meaning to all of these automations now that her father is gone.

There is an interesting attention to the language of the body. One scene focuses on Rem’s daily swimming practice, and the expectant and open state of mind that results after he has had his swim. In another, he talks about observing the workers on the various construction sites he visits, noting not only cultural differences in how they work individually or together but also differences in energy and morale. Aware of the criticism of starchitects, of the fantasy of globe-trotting designers plopping down their weird signature forms wherever they go, Rem says that it is not that he is interested in making the same thing everywhere, but rather that he has been allowed to do different things everywhere. My friend Jacob Dreyer wrote recently in Artforum to question the logic of OMA in our new political era: “Now our governments are more radical than our artists, who tag along behind asking the government to be careful, to consider unintended consequences.” I feel that the utopian logic that Jacob ascribes to OMA’s past work is inaccurate and ahistorical; the point has always been to engage with messy realities and, if anything, the mess to be engaged with now is only proliferating.

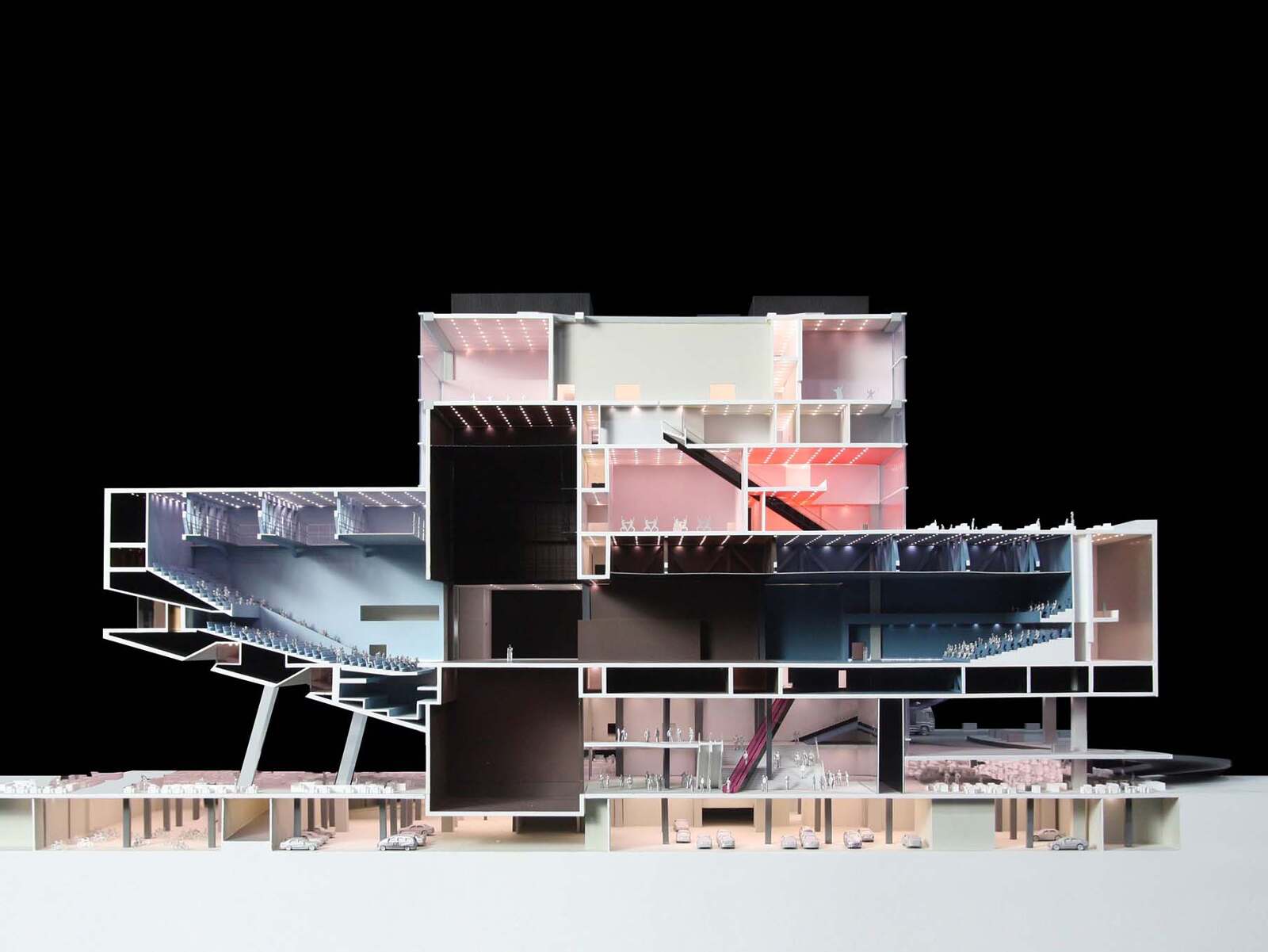

Sketches and models for TPAC by Petra Blaisse, with the combined theater space visible at right

These markers ring true to my experience of OMA projects: they embrace the impure, they celebrate the rigor of internal logic, they are more platform than stylistic statement, and they create possibilities for unexpected forms of movement. Later this week I will be back at TPAC, affectionately nicknamed the egg-on-tofu, for a performance of Łukasz Twarkowski’s Respublika. This production will, for the first time, open up two of TPAC’s three theaters to each other, creating an unexpected mega-space that has taken quite a bit of time and engineering to realize. A couple months ago, when I toured the building with Hans Ulrich Obrist and Chiaju Lin, who directed the project on behalf of OMA, Rem phoned in with excitement to hear our feedback. Living in Beijing during the construction of the CCTV tower, I heard a lot about the circularity of media production, and how the design of the building would allow for a public loop providing visibility into the circulation of the image. That being Beijing, a lot of the transparency was eventually dropped from the program. But in Taipei, TPAC has the Publicloooooop, a route that runs through the building offering glimpses of backstage production facilities as well as views of the surrounding neighborhood. Like buildings themselves—like children—ideas have afterlives of their own, popping up in unexpected places.

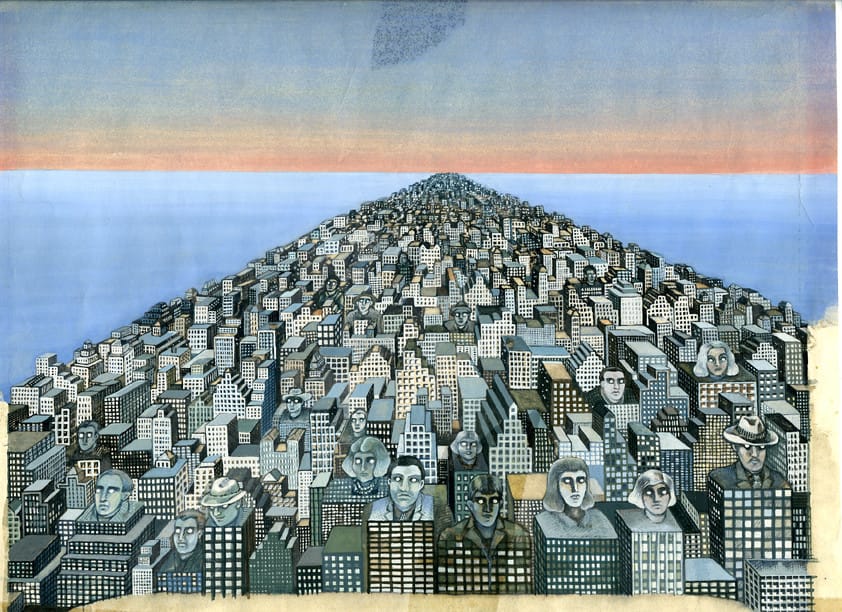

Work by Madelon Vriesendorp

In Venice for the Biennale, Rem speaks of a full-circle moment to see both of his children engaged with his professional life and with the creative world. Aside from Tomas, director of the documentary, Charlie is a photographer and artist. Their mother is Madelon Vriesendorp, a co-founder of OMA and the brilliant artist behind many of the defining images of the OMA universe, like Flagrant délit (1975), seen on the cover of Delirious New York. Madelon and Rem divorced in 2012. Rem’s partner Petra Blaisse has collaborated on many OMA projects through her firm Inside Outside, including both the landscape architecture and interior concepts for TPAC. Rem D. Koolhaas, nephew of Rem, is the founder, with Galahad Clark, of footwear brand United Nude.