Shorts

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Shorts is a regular column with links and commentary on family culture.

Juergen Teller (Talk Art)

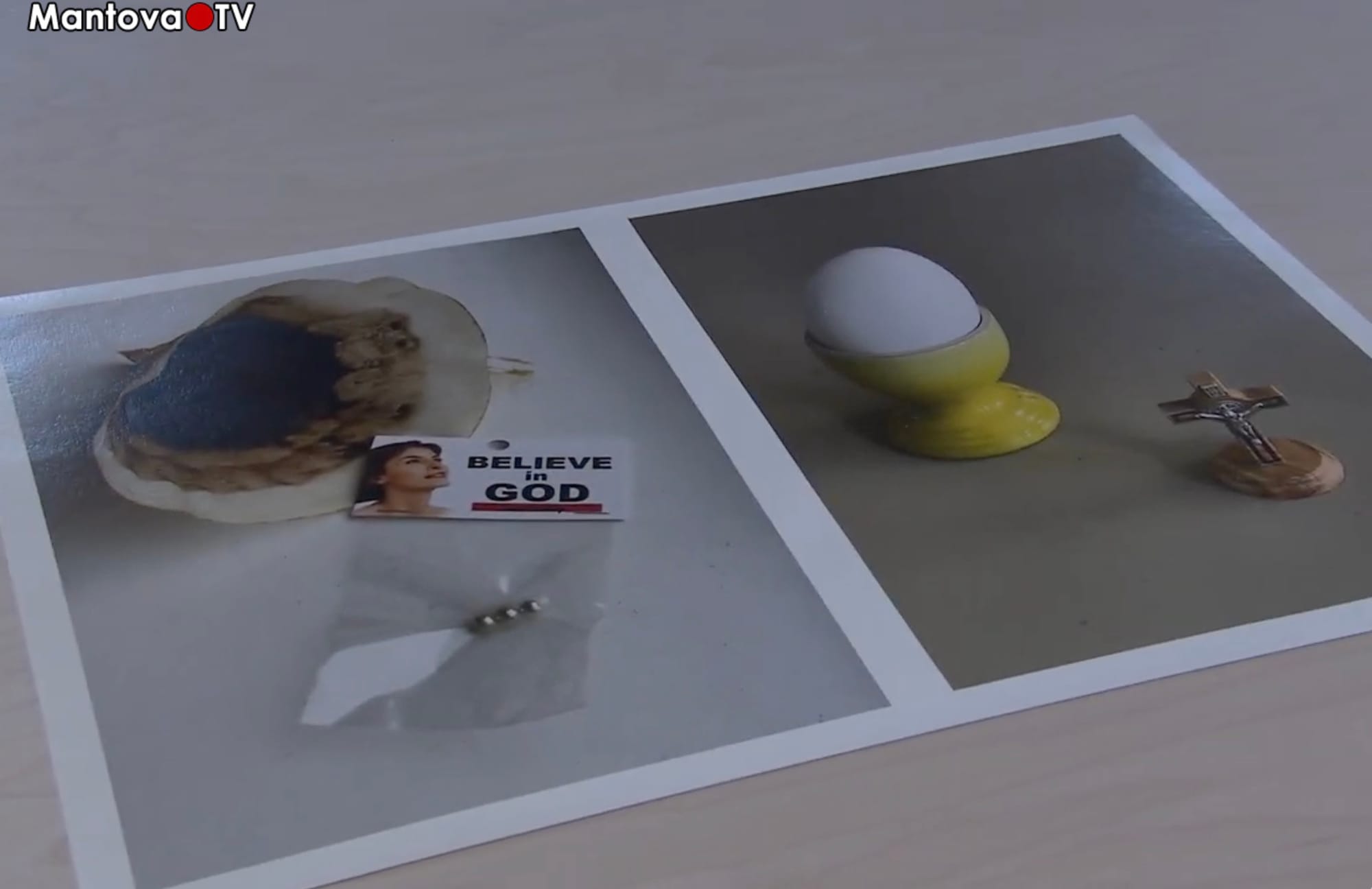

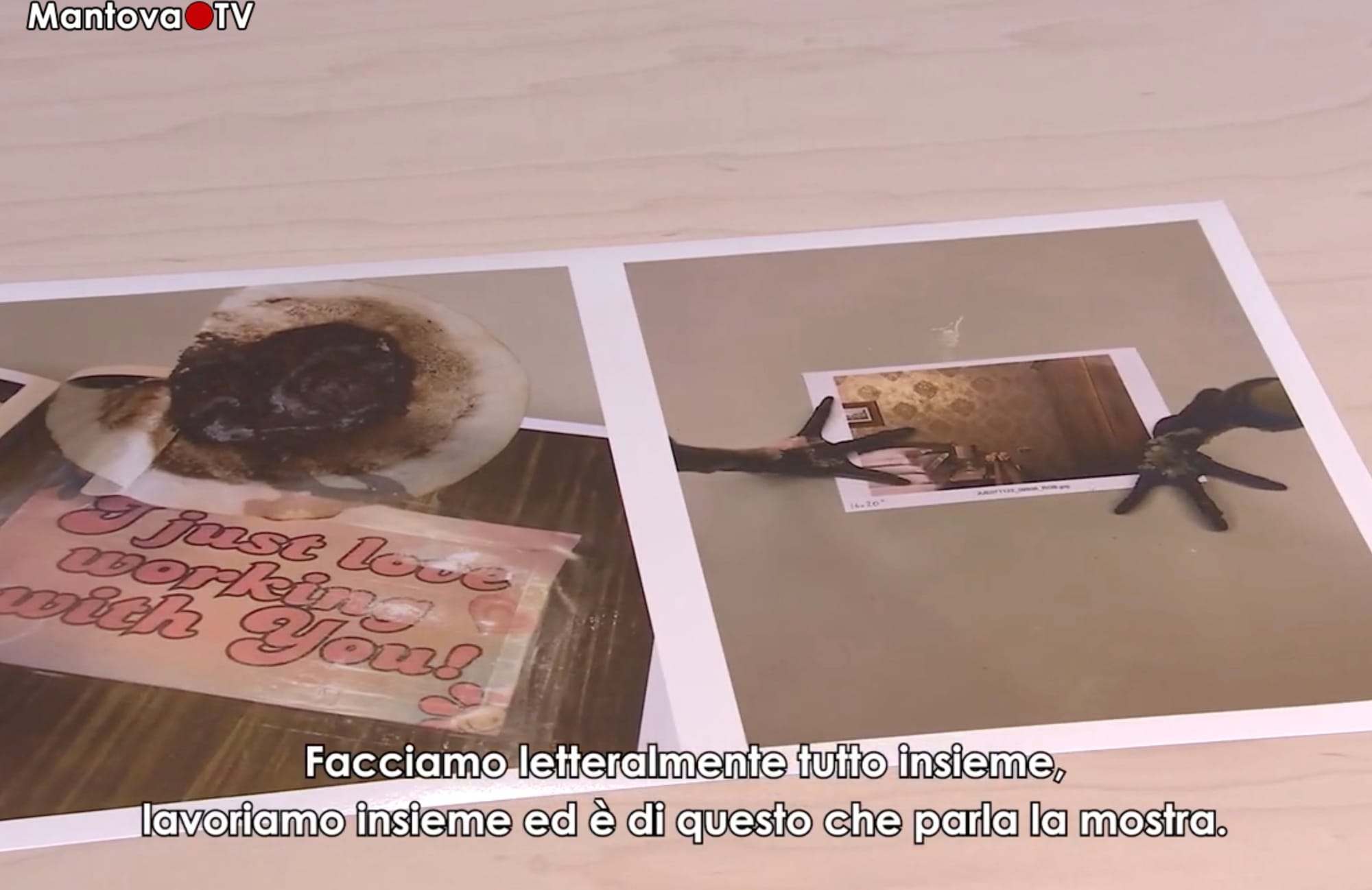

On one of the millions of artist interview podcasts I listened to last week, Juergen Teller introduced his summer exhibition “7 ½” at the Galleria degli Antichi and the Palazzo del Giardino in Sabbioneta. The show is titled after the duration to date of his relationship with Dovile Drizyte, who has become a creative collaborator as well as a romantic partner. Last year they released a beautiful Steidl book together called The Myth consisting of 97 photographs of Dovile posed with her legs in the air in allusion to the idea that the pose improves the odds of conception, one in each room of the Grand Hotel Villa Serbelloni on Lake Como. Juergen also described a new project in which he photographs the pourover coffee he has made for Dovile each morning for the last seven and a half years, then photographs the environment around the coffee. This series caught my imagination for its tenderness and simplicity, but I haven’t managed to find any images yet, save these screengrabs I’ve borrowed from a report on the exhibition by Mantova TV.

I always enjoy the contrast between the high gloss of commercial fashion photography and the offhanded nature of the personal and art images that fashion photographers take. Juergen Teller has never been afraid to put his children in front of the camera: Iggy, his daughter with Dovile, is the star of this Document Journal portfolio recreating some of his iconic shots while Lola, his eldest daughter with Venetia Scott, was a part of some of these shoots the first time around. Ed, his middle son with Sadie Coles, is the heart of the 2006 photobook Ed in Japan. For his retrospective at the Grand Palais Ephémère a year and a half ago, Teller put together an eerie triptych: on the left, a photograph of himself as a baby taken by his father; in the middle, an enlarged copy of a newspaper notice of his father’s death, “Mit Auto den Freitod gesucht?” (“Suicide by car?”); at right, a photograph of his mother hamming it up with a taxidermied alligator.

The exhibition was titled “I Need to Live” in reference to the ongoing choice to not follow his father. In 2003, Teller shot a series of photographs at his father’s grave. In one, Mother and Father, his mother faces the camera, partially crouched down, arms outstretched like a keeper in front of a goal. In another, Father and Son, Teller himself holds a lit cigarette and a bottle of beer, one foot resting on a football, completely nude.

Yiyun Li (New Yorker)

I did not particularly want this to become a theme for this week, but Yiyun Li’s writing on her sons’ suicide gives us some of the most eloquent lines there could be on what it means to choose to live, and what it means to create the conditions to allow others to carry on with their own choices in life, whether they choose to live or not:

If I train my mind on the happy moments, the framework for living seems sturdy enough. And yet it is not an indestructible shelter from catastrophes. A mother dedicating herself to the framework for living is like a ship-builder building a vessel, not asking whether the voyage is to be through calm seas or tempests, not pondering whether there will be a tomorrow or not.

Proust (Personal Canon)

In her newsletter, Celine Nguyen quotes Roger Shattuck on the meaning of Proust: it’s about “human beings faced with the appalling responsibility of living our lives.” The whole essay is wonderful and very much worth reading.

Art Collecting with Kids (Art Basel)

A collection of really cute photographs of collectors’ children tagging along to studio visits and helping to install artwork in vacation homes.

Artist Homes (The Guardian)

Katy Hessel writes on visiting artist homes, and understanding domestic space as an environment every bit as important as the studio to the conception and production of the work. She mentions artists we have looked at here: “Ruth Asawa looped her wire sculptures on the kitchen table surrounded by her six children,” and “for Bourgeois, her house—both a prison and site of freedom—was her muse.” I think this would be a great topic for a book.

Sarah Manguso (LARB)

I haven’t yet had a chance to read Sarah Manguso’s new book Questions without Answers, which collects replies to “What’s the best question a kid ever asked you?”. This short interview touches on the book itself as well as her philosophy of education, and includes a couple gems:

Before I was a mother, I thought of my life as my very own masculine-coded hero’s journey. Now I raise my kid and I write, and I find both of those practices so much more interesting (and more heroic?) than the life I wanted when I was young.

And for this week, I’ll end with this:

There’s a huge overlap between making art and raising a child—and there’s an overlap between making art and being a child.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Shorts is a regular column with links and commentary on family culture.

Peter Cook’s Play Pavilion (Serpentine)

In a bit of serendipitous timing the Serpentine announced the launch of their new Play Pavilion the week that Hans Ulrich Obrist arrived in Taiwan for the first time for a few days of lectures, interviews, studio visits, and meetings with architects and collaborators. Intended to provide space and context for activities involving families and young people, the inaugural pavilion will commission Archigram’s Peter Cook (who also happens to have an exhibition at MoCA Taipei later this year) with the support of LEGO. This is something that I think every museum and perhaps every park should be doing: commissioning artists for playgrounds. (Indeed this is one of the imperatives of Nostos and one of the categories of projects we are pushing forward most urgently.)

I think we are as direly in need of novel approaches to play as we are so desperately in need of new ways to engage with art. They can be permanent or temporary, they can be sculptural or interactive, they can be huge or tiny, they can even be fun or frustrating. In 2022, the Serpentine worked with Alvaro Barrington to build a basketball court in Bethnal Green, which he brilliantly referred to as a landscape painting. That year will probably be remembered as the high-water mark of social practice, which now appears to be shifting and evolving in response to the demands of our new political moment. This summer, Cook and LEGO together are an inspired choice for an initiation because LEGO is such a fundamentally metabolic, revisitable, plastic way of thinking through material. The Play Pavilion opens 11 June and I can’t wait to visit.

Louise Bourgeois (Fubon Art Museum)

Our first stop in Taipei last week was to Fubon Art Museum’s ongoing Louise Bourgeois exhibition “I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you, it was wonderful.” I first visited when it opened in mid-March, which turned out to be a highly araneidan week as we moved from the mid-sized spider in Taipei to the enormous one installed outside of Bangkok and finally to a diminutive one at a gallery show in Hong Kong. The exhibition in Taipei has traveled from the Mori Art Museum, where it was a slightly larger presentation. Exhibitions at the Mori are invariably installed with an enviable level of slickness: you’re dumped right in, then impelled onward through a combination of narrative and crowd flow, and finally extruded through the gift shop, where the merch is reliably excellent. Everyone I know now has “Hell and Back” either on a throw or on a hoodie. In Taipei the museum, which just opened last year, is exploring how its space can be used with each exhibition. The triumph of this show is the installation of Crouching Spider, the only work that can really make use of the architecture. FAM is essentially a Renzo Piano pavilion, open to the street with dynamic glass windows, and this nesting sculpture can take advantage of that relationship between inside and out to a powerful degree. I imagine we’ll see more of that kind of dramatic use of the space in the future.

The second spider of that week was the epic Maman installed at Khao Yai Art Forest a few hours outside of Bangkok. (I say second but of course there were multiple other spiders at Fubon as well, including the excellent 1997 version crouching over a cage.) It is truly one of the great experiences of public art wherever you encounter it, whether in Tokyo or outside Seoul (or Arkansas or Ottawa, though I haven’t had the pleasure). Originally commissioned for the Turbine Hall—the first work to occupy that space—it will be returning to the Tate Modern next month to mark its 25th anniversary. Context is everything, and in Khao Yai the spiritual dimension is activated to particular effect, part of a day-long trail through secondary forest and blazing sun that also includes the rewilding stupa fragments of Ubatsat and a mesmerizing fog by Fujiko Nakaya. Here you can put your back to the ground, your hand to the bronze, and squint up at the marble eggs against the sky with just the sounds of wind and insects and a little laughter.

But my favorite spider was probably this delicate little one in a corner of her show “Soft Landscape” at Hauser & Wirth in Hong Kong, which opened as we arrived there from Bangkok. All of the bronze spiders come in different textures and there are distinct preferences among collectors and curators: Maman is rough-hewn, almost industrial in its composition, while Crouching Spider is considerably more naturalistic, tense with twisted muscle. This tiny Spider falls somewhere between the two, with the welding marks of the former but also a bit more of the hand to it, its body with something of a Giacometti to it. What makes me tingle is the one limb that so tenderly cradles the ostrich egg with an effervescence of care and affection.

It is well known that Bourgeois ascribes to her mother/spider the qualities of creation, industriousness, and protection. Here we see that this nurturing is not a function of scale.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Shorts is a regular column with links and commentary on family culture.

Hervé Guibert (Magic Hour Press)

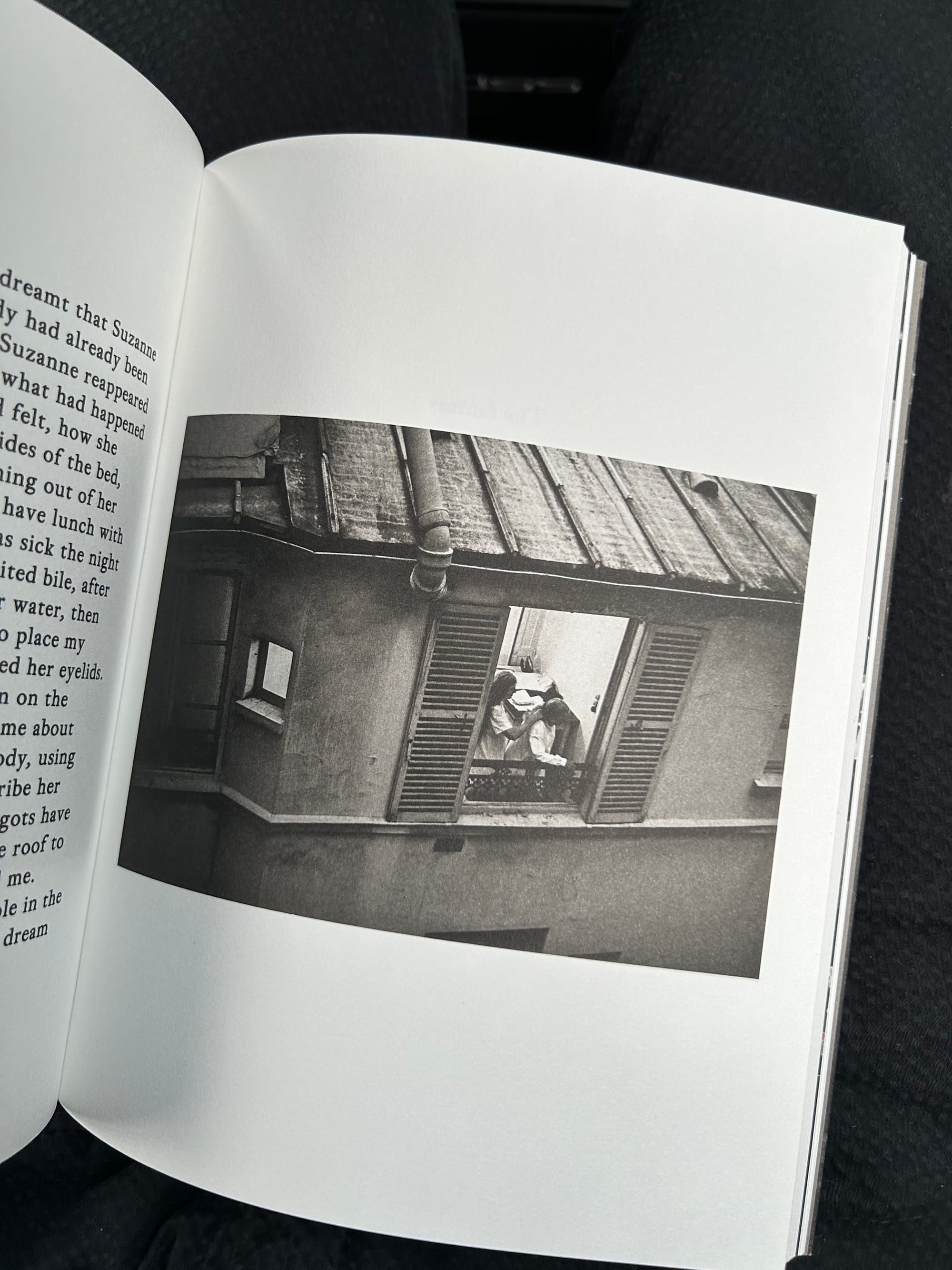

My car is in the shop so I have an extra hour or so of reading time on the bus. This morning I read, twice, through Hervé Guibert’s photo novel Suzanne and Louise. Guibert has become one of the most important touchpoints for autofiction, and this book I find fascinating for its beautifully skewed take on how an artist might turn family life—his own and, simultaneously, someone else’s—into the material of his work. It’s a weird, weird little story, consisting of 44 black-and-white photographs of his two elderly great-aunts in their Paris home interspersed with snippets of text on their day-to-day lives, how they came to lives such lives, and his process of getting to know them and, indeed, work with them, as they become artistic collaborators.

What emerges, unexpectedly, is a lived theory of photography, not so different from how Roland Barthes’s theory of photography in Camera Lucida emerges from a photograph of his own recently passed mother as a young girl—a photograph Barthes describes but never shares. In his text, Guibert describes his aunts’ approach to their images “as if photography were a sacrificial practice.” In the prologue: “They perform, for him, a dramatization of their relationship.” The young artist participates in an improvisation that becomes a real part of his life. The art is the life, and the life is the art. There’s no distance between them. Guibert published the book at the age of 25; he died of AIDS at 36, which is also my age as I write this.

Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie (Isabella Bortolozzi)

Annie Ernaux, too, has become one of the core reference points of our current strain of autofiction or memoir, though on the opposite end of the spectrum. She lives within memoir, speaking to the truth of experience conveyed through literature. This past weekend marked the close of an exhibition of photographs by Ernaux and Marc Marie at Isabella Bortolozzi in Berlin. Titled “BEDROOM, CHRISTMAS MORNING” after a photograph in the show, it is a simple project of 14 images: over the course of their year-long affair, the lovers photographed the mise-en-scene of the morning after, the state of the room after their liaisons—mostly clothes on the floor in varying states of disarray.

They, too, turned their relationship into an art project, writing short texts to accompany each image that they only shared with each other after the close of the year. A book bringing together their words and photographs has just been published by Fitzcarraldo, though I have yet to read it. The affair coincided with Ernaux going through chemotherapy, a context that shifts ever so slightly the suggestions of touch, of intimacy, that are inherent to these pictures. A superb essay by Jonathan Alexander in the Los Angeles Review of Books looks at both of these recent books in terms of the “theatricality of the quotidian” and the structures for living that they propose. I think that structures like these are some of the most life-giving things that we can learn from artists. Life as a project.

Ruth Asawa (New York Times)

By way of previewing Ruth Asawa’s upcoming retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Hilarie M. Sheets visits the artist’s home in the city. I have to present this without comment:

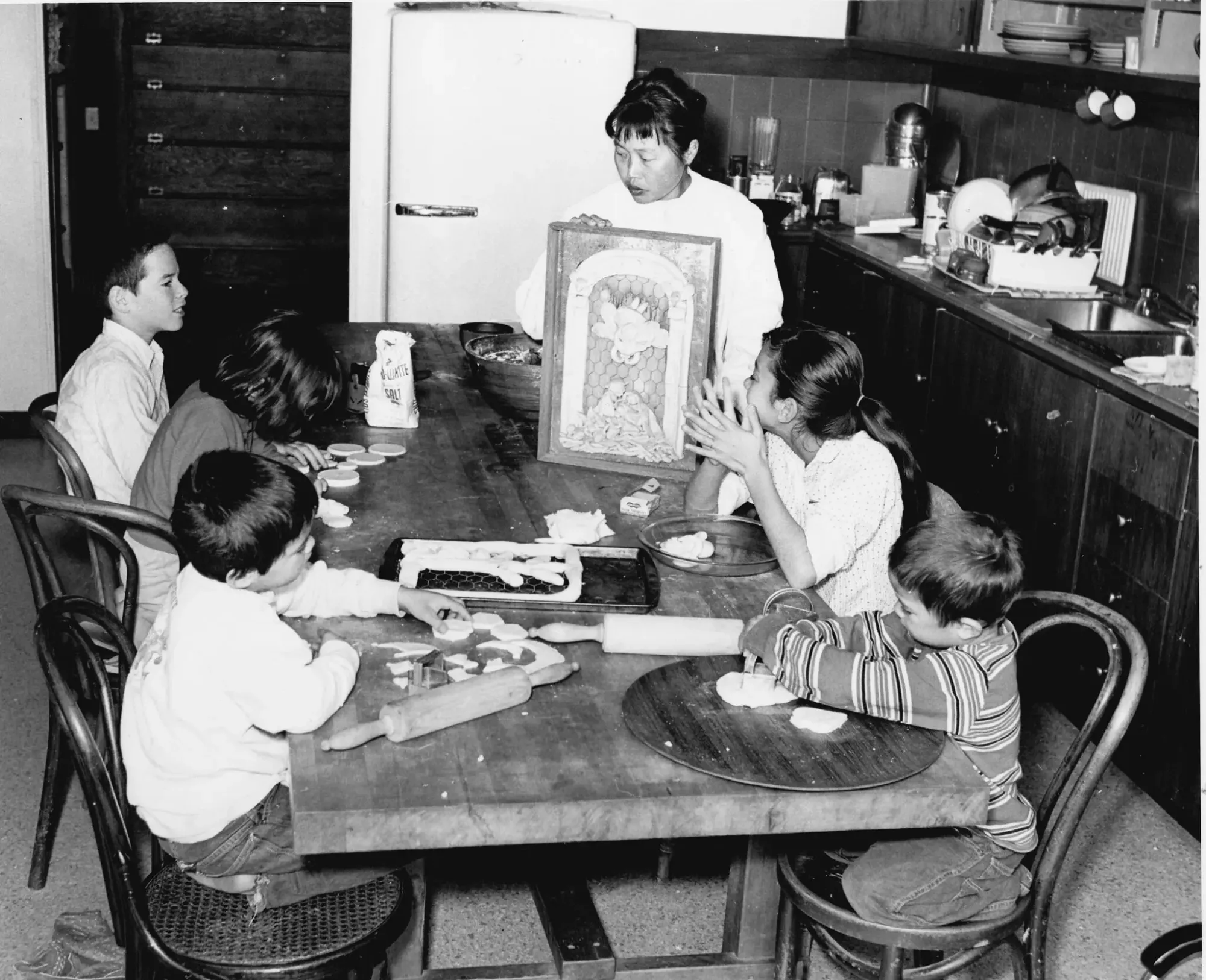

A lot of times she worked right here,” [Asawa’s youngest child] Paul said, pointing to a discreet hook at the center of a double-wide door frame between the living room and kitchen, where Asawa would hang her looped-wire works in process. “She could sit, or she might have to lie down,” Paul said, as the scale of her curvaceous forms grew, adding that it was a convenient spot to monitor what was cooking for dinner. At the long butcher block kitchen table built by [her husband] Albert, Asawa led group sessions sculpting figures from homemade baker’s clay (a mixture of flour, salt and water), or decorating eggs or making origami by day and family meals by night. “The most important thing to this family was that we sat down to dinner together every single night,” Asawa once told an interviewer. “There were eight of us at the table, plus friends."

There is a new book out by Jordan Troeller that I am dying to read called Ruth Asawa and the Artist-Mother at Midcentury that looks at motherhood “as a means to reimagine the terms of artmaking.”

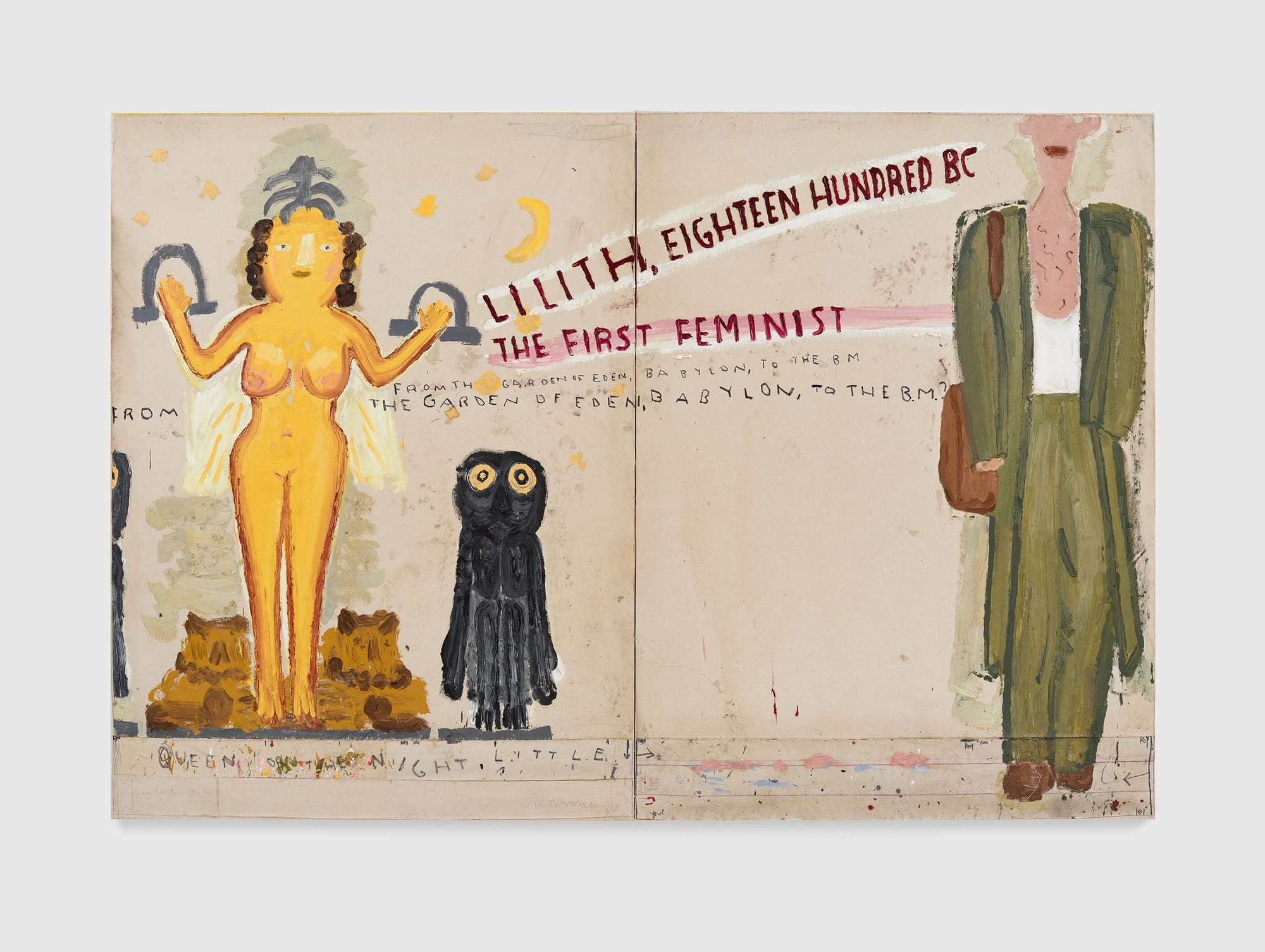

Rose Wylie (Great Women Artists)

Nonagenarian painter Rose Wylie opened an exhibition at David Zwirner in London this week, and promoted it with a series of wonderful studio visits, including an excellent episode of Katy Hessel’s "Great Women Artists" podcast. Born in 1934, Wylie studied art, stepped away from her practice to raise her children, and then returned to the work in her forties newly invigorated and feeling like she had a lot more to bring to it.

I love to hear the stories of how different artists position the work of the home and the work of the studio in relation to each other: for every famously uninvolved mother like Alice Neel or Celia Paul there is a Ruth Asawa building sculpture in the kitchen or a Rose Wylie putting children first. In the podcast Wylie says that she believes that being a mother was an important part of life, and that being a wife was an important part of life. She recalls how her tutors in art school looked down on women who they expected to marry and have children and walk away from art. They were right, she concedes—but not exclusively right. She came back. And, for her, the walking away was not a defeat but part and parcel of the whole thing.

Ed Atkins (Tate Britain)

I can’t wait to see Ed Atkins’s retrospective at the Tate Britain this summer, which by all accounts is an expansive staging of his career. For me Ed is the ultimate poet of the digital self, reflecting back at us how we collapse and inflate ourselves in spaces we can hardly understand with our physical bodies of flesh and blood. Family has become an important part of his work, particularly in the last few years after he became a father—his artist books’ of the post-it note drawings for his daughter’s lunchbox first brought him onto my Nostos radar. But since then, I’ve come to think of this lens as less specifically about artist parenting and more generally about how artists situate their practices within their lives, and Ed’s work on his own parents fill out this picture. Some of his most significant films frame these relationships one by one: The Worm (2021) was a conversation between his own avatar and his mother, focusing on a family history of depression in the depths of the Covid pandemic.

In the new film Nurses Come and Go, but None for Me (2024), an actor reads journal entries that Ed’s father wrote as he was dying of cancer while the artist was in school. In his review, Adrian Searle describes the triangulation of parent, artist, and child:

After the reading is finished Peter and Claire play a game devised by Ed Atkins’ young daughter Hollis Pinky. Peter has now adopted a further persona, and lies on the floor, and Claire, taking the role Ed Atkins used to play in this once-private game, first pretends to be an ambulance, then some sort of doctor, who attempts miracle, fantasy cures for imaginary ills, games of coping and resuscitation, of childhood fears being allayed through play.

Writing on these attempts to “catch the irretrievable moments as they pass,” Laura Cumming says that Ed’s child resists “all this projected significance.” So it goes.

The Guardian loves Ed: Adrian Searle gives him five stars, Laura Cumming only four, and Tim Jonze shares an interview.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about making a home at the intersection of art and life. Shorts is a regular column with links and commentary on family culture.

Noah Davis (Barbican)

The Noah Davis exhibition at the Barbican is a celebration of the intersection of painting and community. Painting can be a solitary practice, particularly in LA where the commute from home to studio can be undertaken in the automotive bubble, but with Noah there is a considered approach to painting as a social practice that I find formally beautiful.

First there is the way that he worked beyond painting, founding the Underground Museum, a unique neighborhood institution that turned the experience of the contemporary art museum into a community project. The Barbican exhibition includes restagings of several UM projects, including its infamous debut exhibition, “Imitation of Wealth,” for which Noah recreated well-known artworks held in museum collections that, at the time, could not or would not lend to UM, as well as a later William Kentridge exhibition that UM organized with MOCA curator Helen Moleseworth.

Then there is how this whole social practice was a family affair: Noah founded the UM with his wife and brother, both of whom are also artists: Karon Davis comes from theater and creates sculptural tableaux, while Kahlil Joseph is the director behind important films shot in collaboration with Kendrick Lamar, Beyoncé, and FKA twigs (as an aside, his work is fantastically adept at capturing the sense of place, m.A.A.d. for Los Angeles and Fly Paper for New York).

Finally, there is the content of Noah’s painting, which alludes to social dynamics on a macroscopic level in operatic compositions of bodies among modernist architecture and then zooms in on the person-to-person connections that make and break these wider structures. One of my favorite paintings of all time is Single Mother with Father out of the Picture, its title defining its composition and making space for the most incredible interplay of faces, skin, domestic interior, painting-in-painting. Or 1984, which pictures his wife Karon as a seven-year-old in a Halloween costume. Not everything is biographical; many of Noah’s most important bodies of work are more conceptual in nature. But I’m pulled in by the place where biography meets practice.

The pièce de résistance in London is Painting for My Dad, an oversized piece more than two meters wide, a dark and looming picture hung on a black wall. Finished shortly after the artist’s father died and a couple years before his own untimely death from cancer, Painting stares into the void with terror and longing and tension and cold acceptance. In his short career, in his short life of 32 years, Noah packed in far more than the exuberance of some fantastic paintings—the rich scaffolding of a social structure for how life might be lived.

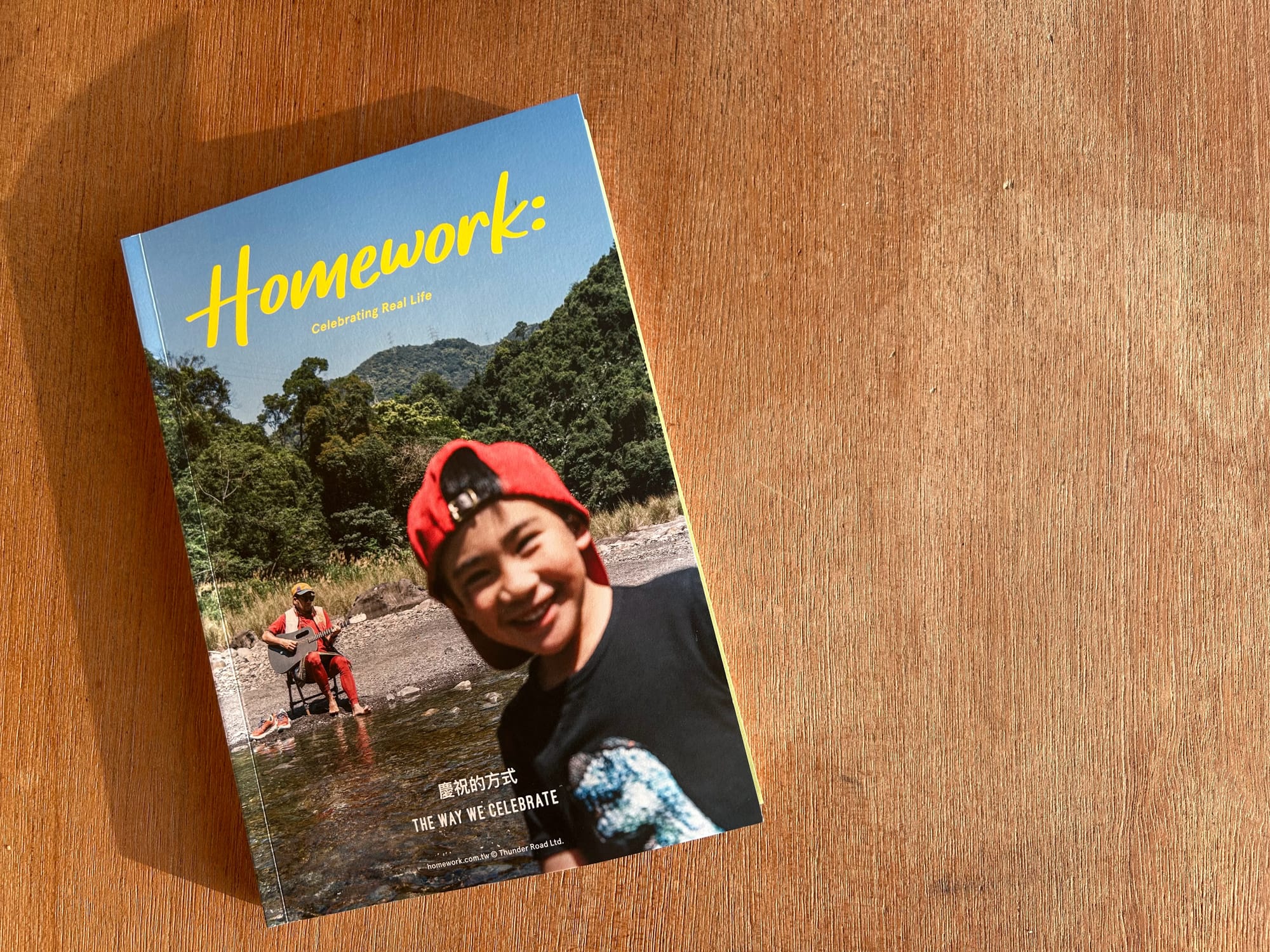

Homework Magazine

I was very happy to recently receive in the mail a copy of the first issue of Homework, a new Chinese-language magazine published by Eileen Chien. I met Eileen and learned about Homework through its creative director, Amy Chang, the brilliant graphic designer who I first worked with when I was editing LEAP and invited her to guide our editorial art direction. Since we both moved to Taipei she has become a close friend, so it's great to see her making creative strides while bringing up her family!

Eileen, too, runs a very creative family (her husband is a music producer who has published on music appreciation for children). The tagline of Homework is “Celebrating Real Life,” and it’s positioned as a lifestyle magazine for people with children, featuring profiles of parents and families of various interests and configurations, as well as Taipei restaurant reviews, recipes, and recommendations for toys, apps, products, books, and music. It’s an approachable sensibility, and a nice addition to the stable of design parenting magazines, which has been lacking ever since Kindling decided to stop publishing after just three issues two years ago. Lately I’ve also been enjoying the offerings from Anorak, which are delightful but a slightly different thing—magazines for children rather than lifestyle magazines for people who happen to have children. Homework positions itself somewhere in the space in between; let’s see how they grow.

Nostos is a weekly newsletter about the intersection of art and life. Shorts is a regular column with links and commentary on family culture.

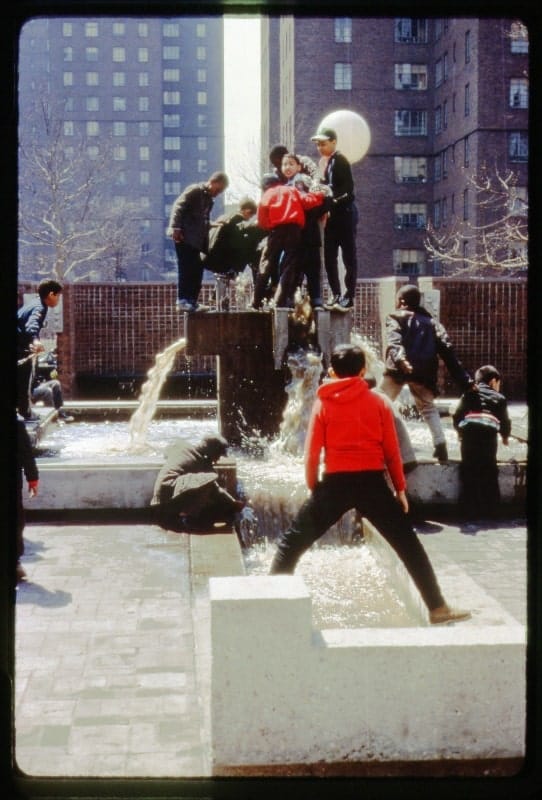

M. Paul Friedberg (New York Times)

Landscape architect M. Paul Friedberg of MPFP passed away last month. His obituary in the New York Times celebrates his contributions to the landscapes of play:

He was inspired by the adventure playgrounds springing up in Europe, where designers had observed children playing in the rubble after World War II. “They realized children really didn’t need formal play environments,” Mr. Friedberg told The New York Times in 1999. “They gave children saws and drills and boxes and called them adventure playgrounds.”

His playscapes are notable for their sheer potential, inviting imaginative uses by children as well as adults. Built in 1965, Riis Park Plaza was a masterpiece, a series of pyramids and stacked volumes for sitting, climbing, running, and jumping that formed an amphitheater, a fountain, a garden, and a playground, each a dedicated space flowing into its neighbors with considered connections. With their inherent sculptural beauty—much like Noguchi’s play equipment—these structures might be better considered landscape design in general rather than playgrounds.

The playable city is a livable city; making environments that are safe, fun, and stimulating for children pays off for everyone. The plaza at the center of the Riis Houses in the East Village has since reverted to fenced-off lawns and standardized play equipment. Friedberg speaks of our tendency to push away out natural inclinations toward creativity and play, and leaves us with this:

There are people whose whole life is dedicated to play, and those are the people we call artists.

Camille Henrot (Hauser & Wirth)

One of my favorite artists, Camille Henrot, has opened her first major New York solo exhibition with Hauser & Wirth this winter. More than a decade ago in Venice, she won the Silver Lion for Grosse Fatigue (2013), a film that gave form to our experience of knowing and feeling after finitude in the internet age; it still rings true, and the conditions it speaks to have only accelerated since.

The current New York exhibition, “A Number of Things,” is cool because it allows us to stick with the theme of playground design. Working with the architects Charlap Hyman & Herrero, she has covered the gallery floor with the thick rubber surface that so often undergirds outdoor play structures, a little bit squishy and a little bit bouncy, ready to absorb broken elbows and damaged egos. Here, the playground consists of sculptures in bronze. The most imposing works, from the “Abacus” series, quote the bead mazes of generic waiting rooms in hospitals, offices, and preschools, bringing them to a heroic scale and materiality while also making them a bit sharper, a bit dangerous—more formally interesting. Other works tame the modernist heritage by turning its artifacts into a pack of dogs on leads tied up at the edge of the park. Play is made serious, even critical, while the self-serious is allowed to feel fragile.

In her interview with Artnet, Camille echoes Paul Friedberg almost exactly:

Playing is how we train for life. Not to mention the fact that there is also a huge liberatory power in play. … Between “A Number of Things” worth figuring out is how and when we came about to divorce play from the imagination.

She is also profiled in Frieze and reviewed in the New York Times.

Chris Ware on Richard Scarry (The Yale Review)

Chris Ware is one of our preeminent graphic novelists, and the man responsible for the most epic New Yorker covers. In the Yale Review (which has become a sleeper hit under the editorship of Meghan O’Rourke over the last five years), he has an essay marking the 50th anniversary of Richard Scarry’s Cars and Trucks and Things That Go. Scarry’s graphic dispatches from Busy Town form the texture of childhood for my generation, to the point that there is a well-known meme that is continually making the rounds:

In his essay, Chris sketches out Richard Scarry’s biography, and the happy series of steps that led to the creation of the Busytown expanded universe. Importantly, Scarry spent the Second World War as an art director across Europe and North Africa, later ultimately moving permanently to Lausanne and Gstaad, where he drew the Busytown books:

Scarry’s guides to life both reflected and bolstered kids’ lived experience and in some cases, like my own, even provided the template for it. And while often sweet and quiet in its depiction of a picture-perfect society functioning measuredly—was Busytown urban or suburban or . . . European? (Where did all those Tudor homes and corner groceries come from, anyway?)—there’s just enough innocent mayhem and tripping and falling to hint at a darker side of things, like failing 1970s marriages and the things on television news that adults were always yelling about.

A decidedly un-American tone runs through much of it. By “un-American” I don’t mean anti-American. Instead, I mean there’s a top-down, citizen-as-responsible-contributor, sense-of-oneself-as-part-of-something-bigger that feels, well, civilized.