Everybody Breastfeeds

Technologies of nursing from Loie Hollowell and Ei Arakawa-Nash

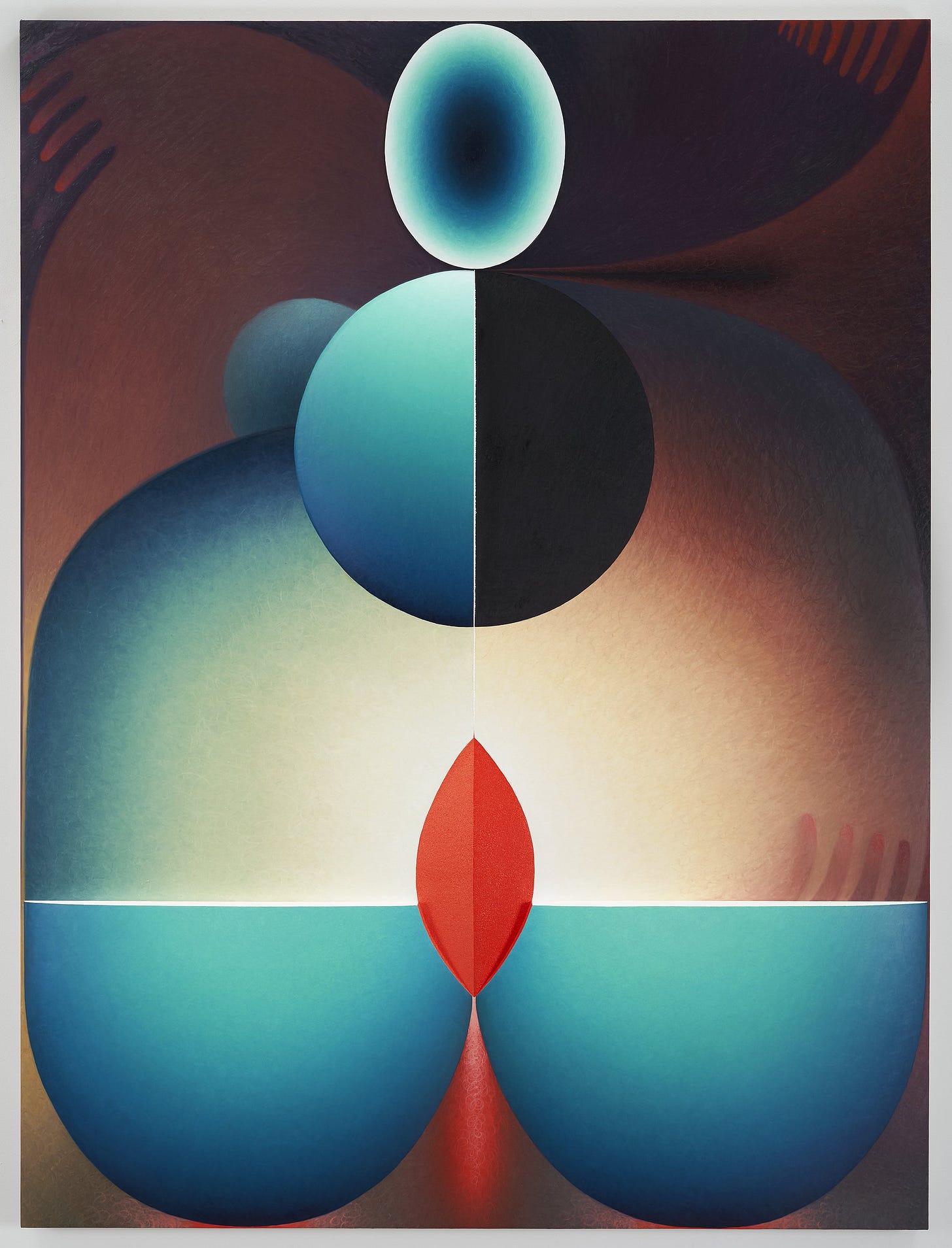

Icon: Loie Hollowell

Icon is a regular column pairing canonical works of art and quotations from pioneering figures in the history of art and life.

“There seems to be the universal knowledge that between the moments of absolute tension and expenditure of energy, there must also be the moments of relaxation.”

Few artists have become as central to conversations about art and parenthood as Loie Hollowell. Many of the others who occupy a similar position focus on the labor of parenting (like Caroline Walker). Loie, to my mind, comes in with a really unique contribution in the form of the body of the mother—the true heir to Judy Chicago and Georgia O’Keeffe. She started connected her practice to her first pregnancy in 2018. Of course, her work has always been about the body, her body, the experience of being a body; pregnancy and childbirth, it seems, opened up a line of inquiry that connected pleasure to pain, darkness and light, openness and closure.

I really admire Loie’s willingness to take the sex and sexiness of motherhood right alongside the blood and guts:

It’s important to have many, many, many different perspectives on the birthing body, the fantasy of the birthing body, the actual birthing body, what it feels like to really be inside of it. We need all these perspectives to add on to the history. For me, I feel like my contribution can be one of lived experience and abstraction.

What I most appreciate about how she’s integrated all of this into her practice as an artist, though, is that it doesn’t take the form of a moral imperative, but rather a natural outgrowth. The contours of her practice, the relationship between the body of the artist in the studio and the semi-abstracted geometric forms that result from it, is elastic enough and yet profound enough that it is able to digest all of this and spit it back out in its own mature language.

Loie’s first solo exhibition was just 10 years ago; her first solo exhibition with Pace Gallery happened to be the first show of her pregnancy paintings, in 2019. Now, a decade into her career, we can see something of its arc, from the embodied spirituality and sensuality of the earliest paintings through to the poignant cycle of works from pregnancy to childbirth to nursing.

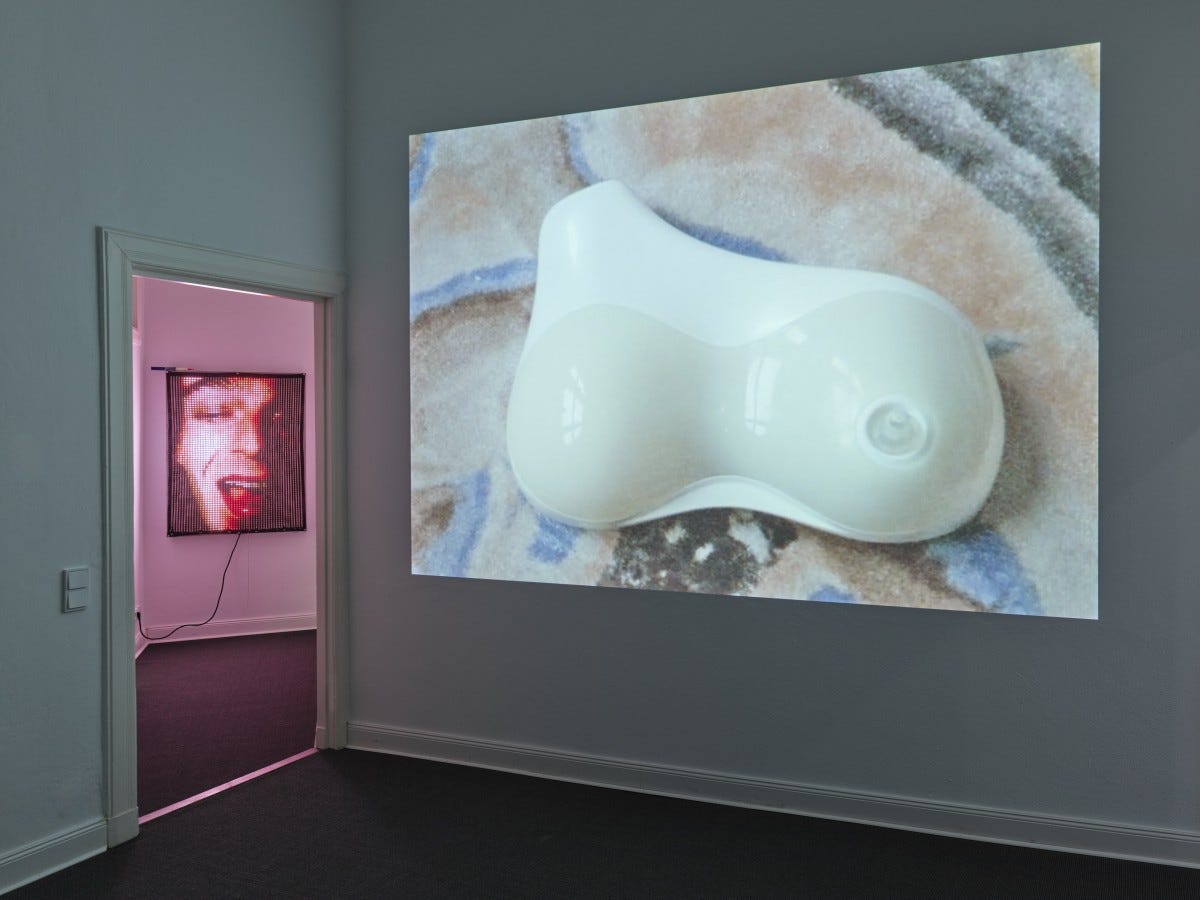

Field Trip: Non-Gestational Co-Nursing

Field Trip is a regular column reporting on exhibitions and institutions.

Ei Arakawa-Nash inaugurates the new Berlin space of Max Mayer with the solo exhibition “Non-Gestational Co-Nursing,” centered on a film of the same title that depicts the artist and his partner nursing their babies with a “prosthetic chest-feeding device” created by Taikan Hoshino and Osamu Takahashi.

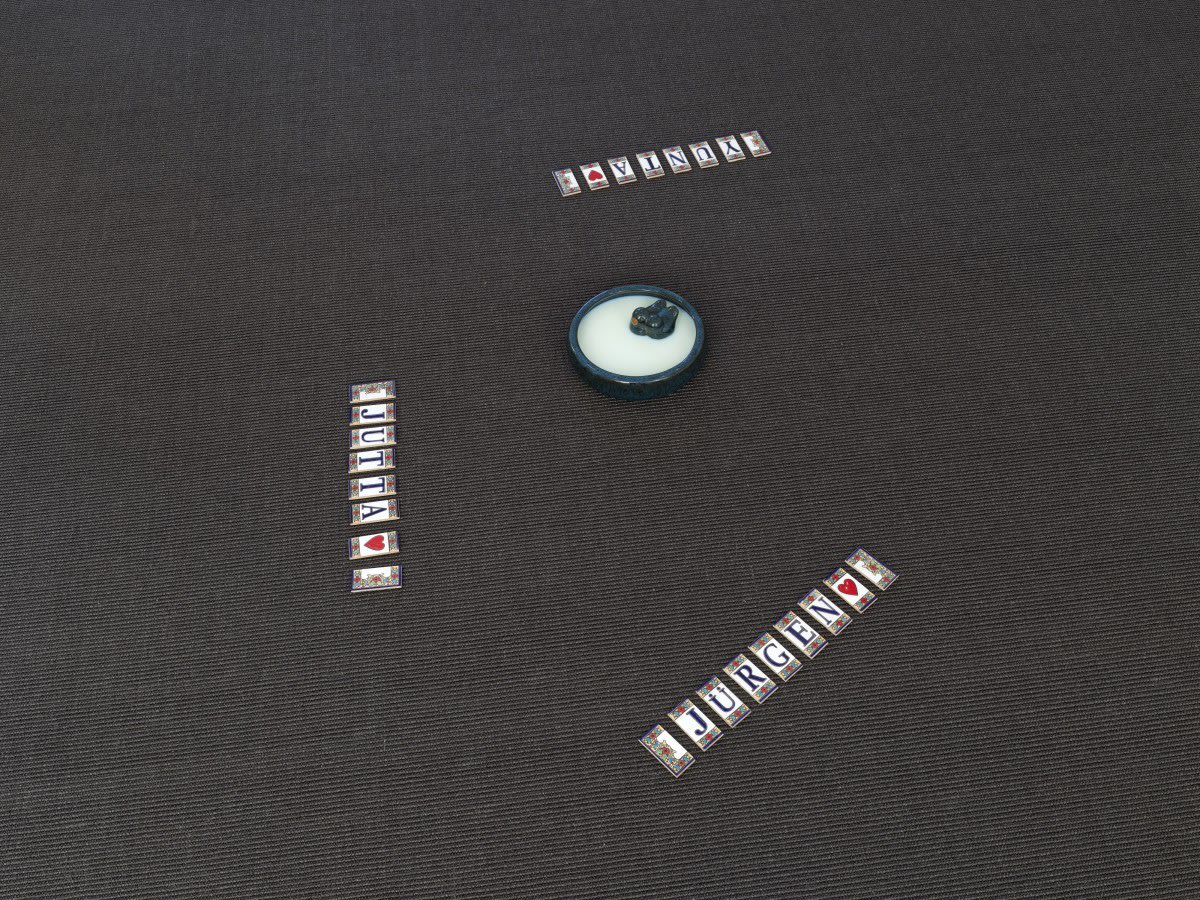

In some ways the exhibition is an extended genealogy of the artist, connecting their professional practice with their more personal family tree as a parent and partner. Ei studied with Jutta Koether, who herself cites Jürgen Klauke as one of her core influences. Ei’s partner, Forrest Nash, is the founder of the website Contemporary Art Daily, an archive of installation shots of exhibitions at galleries and museums. Their children are named Soh and Yunta; Yunta is named after Jutta, triangulating the strands of genealogical influence present in the artist’s life. Jürgen’s work used photography, video, and live performance to trouble the presentation of gender and sexuality, a lineage into which Ei can now insert their everyday practices of parenting in this film and in a series of LED works that pay homage to Jürgen.

Ei describes this stage of his practice:

I am planning to make art with my children until they are around 3 years old. It’s weird to structure such a thing, but that is the age when most adults' earliest recalled memories are formed. I would like my performance to attempt to capture some aspect of the twins’ unrecorded early years.

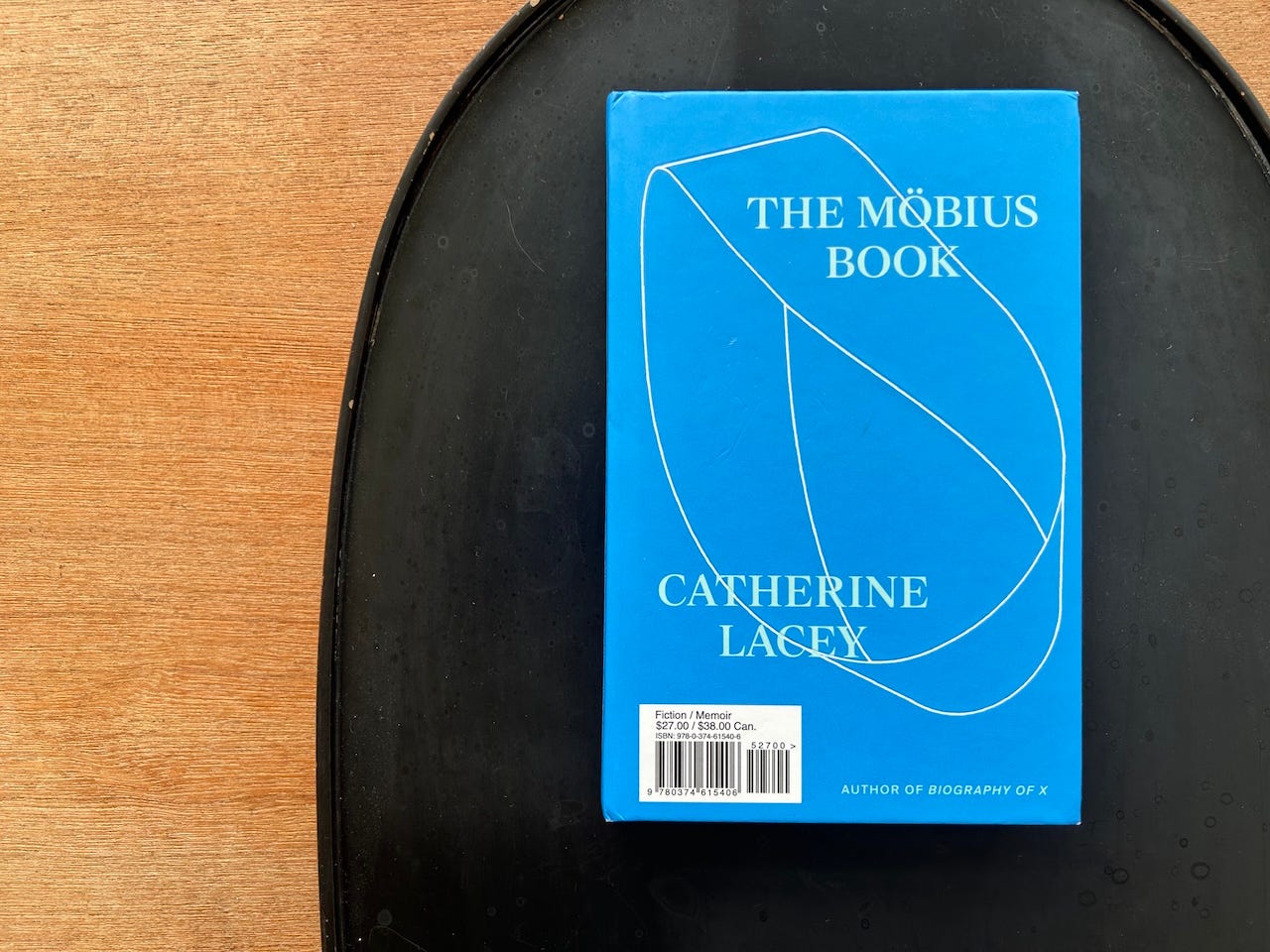

Book Report: Mobius Book

Book Report is a regular column that reads books for, by, and about artist parents.

Catherine Lacey’s Biography of X is one of the novels that has had the greatest influence on my thinking in the past few years. An enigmatic artist, X, has died; our narrator, her lover, sets to unearthing the details of her life, only to discover that the authentic core of the person she loved was invention itself. The story takes place in an alternate present, one in which the American south has seceded (again) and become a fascist theocracy. Catherine mixes in real people like Arthur Jafa, the kinds of artists someone like X would have known in New York, and historical events, so the line between this alternate history and how events have played out in our world beyond the book is always slightly blurry. Biography also borrows postmodernist winks at the archive as a source of data, with metafictional photographs and excerpted interviews and a handful of footnotes. It was pure mind-expanding pleasure to read, and played a part in how I conceived the Nostos project in a couple ways. Biography, clearly, is important to this idea of the artist’s life, and the idea of biography as fiction perhaps even more so. Plus, of course, I love the creative pairing, the idea of art coming into existence through the friction between two people’s distinct practices, their love for each other the catalyst to something new. Two summers ago, I wrote:

On the beach I was reading Biography of X, an amazing experiment in alternate realities that attempts to learn as much as is possible to know about the other from the zero-distance of the Kiss, and to define the self through its relationships. How can we know an artist? What in a life prepares us to understand its work? We have moved a long way from the orthodox New Criticism dissociation of art and life, even after the identitarian interventions. Frances Lindemann wrote in The Drift recently about auto-criticism and the biographical fallacy, and probably worries a bit about over-identification as a risk to the critic. You cannot see the other at all when you are really focused on looking for reflections of the self. In the right place at the right time with the right people, however, I think we’re able to look with true empathy—looking for the other in the self, perhaps. Is that what auto-criticism might be for? That’s where we’re able to see how life enables the work, and how the work enriches life.

Catherine’s latest, The Möbius Book, seems to have been written as if in direct response to these questions. Its format is perhaps even more playful than Biography. You start reading the book and then, a little more or a little less than halfway in, you bump into a page of acknowledgments. The following pages are upside-down. You have to flip it over and start reading again from the opposite direction. This is a break-up book, of which I am something of a morbid connoisseur (Light Years: undefeated; By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept: literally ended up in the ER the night I finished it; The Children’s Bach: doesn’t count because everyone moves back in). I almost called it a break-up novel, but that wouldn’t be quite right. One of the two halves, the slightly longer one, is memoir, told from the perspective of Catherine Lacey in the wake of her break-up with Jesse Ball, who she refers to throughout as The Reason, introduced on the first page as “The Reason I’d turned from inhabitant to visitor” in her own home. (She is referring to moving into a guest room after being broken up with over email, but in a more general sense this displacement is a symptom of all endings, the unwilling relinquishing of a shared understanding of a life, a future, a world.) The other half, the slightly shorter one, is novella, a story about two friends processing a break-up that has destabilized their friend group. (One of them was caught cheating on the third friend by the fourth, who is also the brother of the third.) The novella, presumably, is the fiction that resulted from the period delineated by the fact of the memoir, though of course the whole point of putting it all together is that the fact flows into the fiction and the fiction might be fact. As Catherine puts it in the memoir:

Fiction is a record of what has never happened and yet absolutely happened, and those of us who read it regularly have been changed and challenged and broken down a thousand times over by those nothings, changed by people who never existed doing things that no one quite did, changed by characters that don’t entirely exist and the feelings and thoughts that never exactly passed through them.

The two halves are linked by a page of acknowledgments, a page of credits, and a page of works consulted, linking the work within the work to the work beyond the work, emphasizing the milieu of connection that creates art and providing a shared buffer zone of social reality between these two pieces of fiction. One-and-a-half pieces of fiction. The other links between the two are repeated images: naked swimmers at a rough beach, variously dying and surviving. Another image, an action that occurs in the first couple pages of the memoir and the last page of the novella: a tool is placed beside a teacup. In the memoir it is a hammer and a Japanese teacup so precious it must be destroyed in order to repair the relationship around it. In the novella it is a crowbar and a beautiful gray teacup. In both cases the action is one of place-setting, a composition of mise-en-scene that is charged with meaning. A corner of the world, laid out in preparation for the work to be done. Catherine has a strong sense of this domestic setting, of how home is something that is both material and not:

Hope is visible in the objects in our homes. Identities and plans rest dormant in a stack of books. The kitchen pantry reassures us of our future nourishment. A toolbox is the confidence that we can fix what will break. Little notes to self. Little notes of self. The secret language of things we use to fold life into time, time into life.

The home and the studio, understood side by side:

The Red Studio was an idealized place for Matisse—a room displaying years of work, an arc of one man’s visual language. I love paintings of paintings, Avery said, and the moment she named this category, I loved it, too. Books about books. Films about films. Often I find myself writing about an apparent subject that is concealing an almost opposite object. To write about hatred is to see love, vividly.

In her works consulted, Catherine Lacey notes a number of other writers who I have been working through. She quotes from Gillian Rose, who I would like to return to in more depth, as well as Thomas Merton. There is a constellation there of love as a spiritual practice, something that she believes in with perfect clarity, “faith in another person … faith in something we could not prove.”

Catherine is also on Substack where she is amazing read:

Links: Nina Simone, Feminist Duration, Kids with Phones, Carework, and Placemat Poetry

Adam Pendleton has brought together Rashid Johnson, Ellen Gallagher, and Julie Mehretu to preserve Nina Simone’s childhood home in North Carolina as a house museum, possibly with an artist residency component. I love the house museum format and appreciate this action as artists supporting artists in a political sense: preserving a personal site as a window into the woman behind the work.

Feminist Duration Reading Group

This is a reading group for “under-represented feminist texts, movements and struggles from outside the Anglo-American canon.” I stumbled on the website while I was looking for a Carla Lonzi text that Catherine Lacey mentions at the end of her memoir. They meet monthly in London, but the resources they have assembled in readings and notes available on the website are amazingly deep and incredibly useful.

“My Fellow Parents Have Betrayed Me,” in The Cut

Through the end of year six/ fifth grade my daughter was in the dream situation of going to a school where all devices, smart watches included, were banned from campus entirely—not in bags, not on buses. It was amazing because it left no decisions to individual families. If one kid gets a watch or phone, their friends don’t even see it unless they’re together on the weekends. Now that we have moved up to the middle school campus, the divisions have begun. Some kids are getting flip phones, some already have iPhones, some have their own landlines. Most of them use their school computers to email each other, treating Gmail threads like group chats.

“Too Few People Are Doing the Carework, and Too Many People Are Doing Bullshit Jobs,” in The Auntie Bulletin and The Matriarchy Report

This one is 100% great. Do you like this video format on Substack? Would you like it if I started doing some of the Lives of the Artists conversations over video in addition the edited transcripts I archive here?

“Four Ways of Setting the Table,” in The Common

I really enjoyed this poem by Clara Chiu and thought that this line, in particular, would be an appropriate way to end this week’s letter. As we have moved from breastfeeding to the domestic tableau, all of these ways of nourishing: “A placemat, you see, is a thing of decorum … I have laid out a corner of the world for you.” Click through here to read the whole poem:

Thank you for reading. Until next week—take the long way home. Please share with any friends you think might be interested.