Lives of the Artists: James Jean (Part II)

On balancing bento boxes with school therapy, living in a Frank Gehry gallery, and the tech rotting our kids' minds

In this issue of Lives of the Artists, I’m speaking with the LA-based artist and father James Jean. Lives of the Artists is a regular monthly interview column profiling contemporary artists, asking them to share the connections between their home lives and studio practices. Last week, in the first half of the conversation with James, we discussed some of the sacrifices that need to be made in order to balance an artistic practice and a family life, whether that means carving out space and time for them separately or accepting what’s possible and what’s impossible at a given moment in time. To read that part of the conversation, scroll all the way down to the bottom for the link.

This week, in the second part of the conversation, we get deeper into the nitty gritty of how he sees his life as an artist and his life as a father. James shares some tips he’s learned in being present in his son’s life, and we discuss what we as parents are looking out for in the world today in terms of educating and nurturing our children.

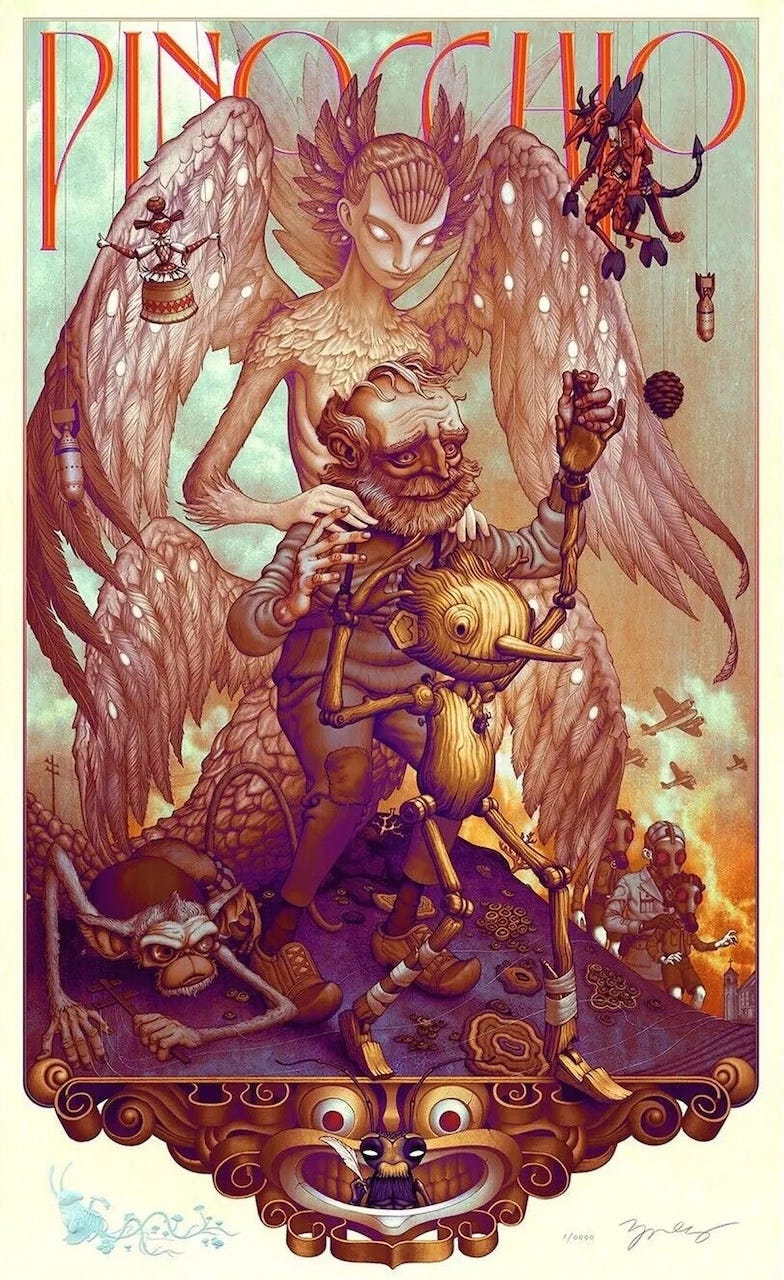

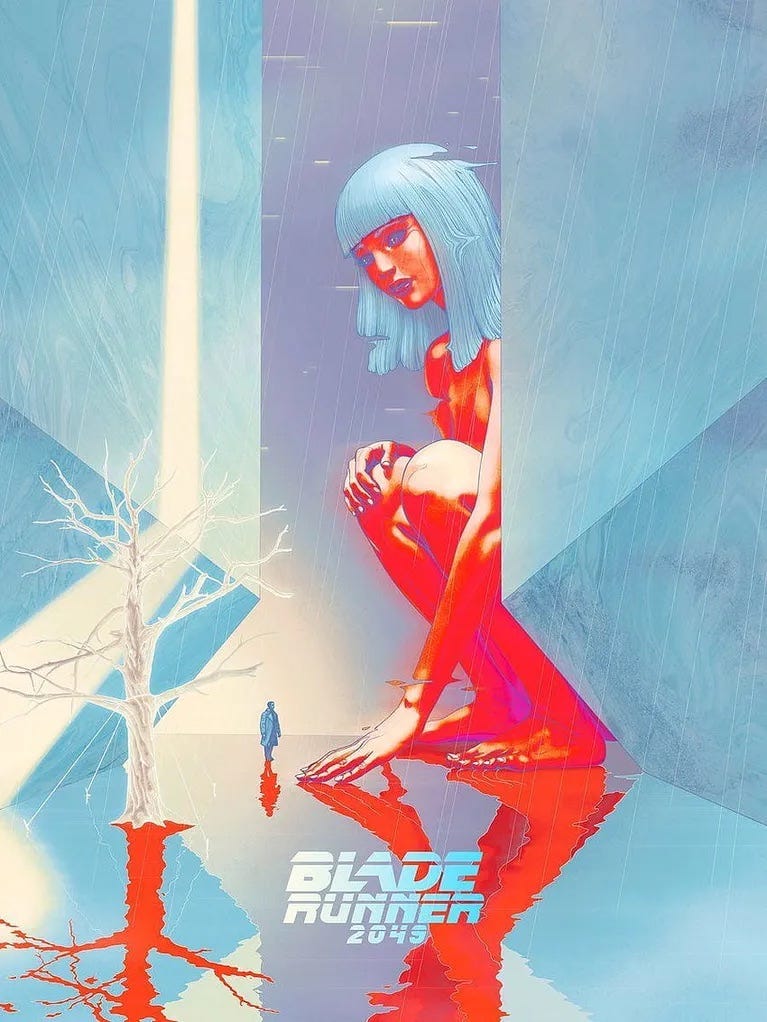

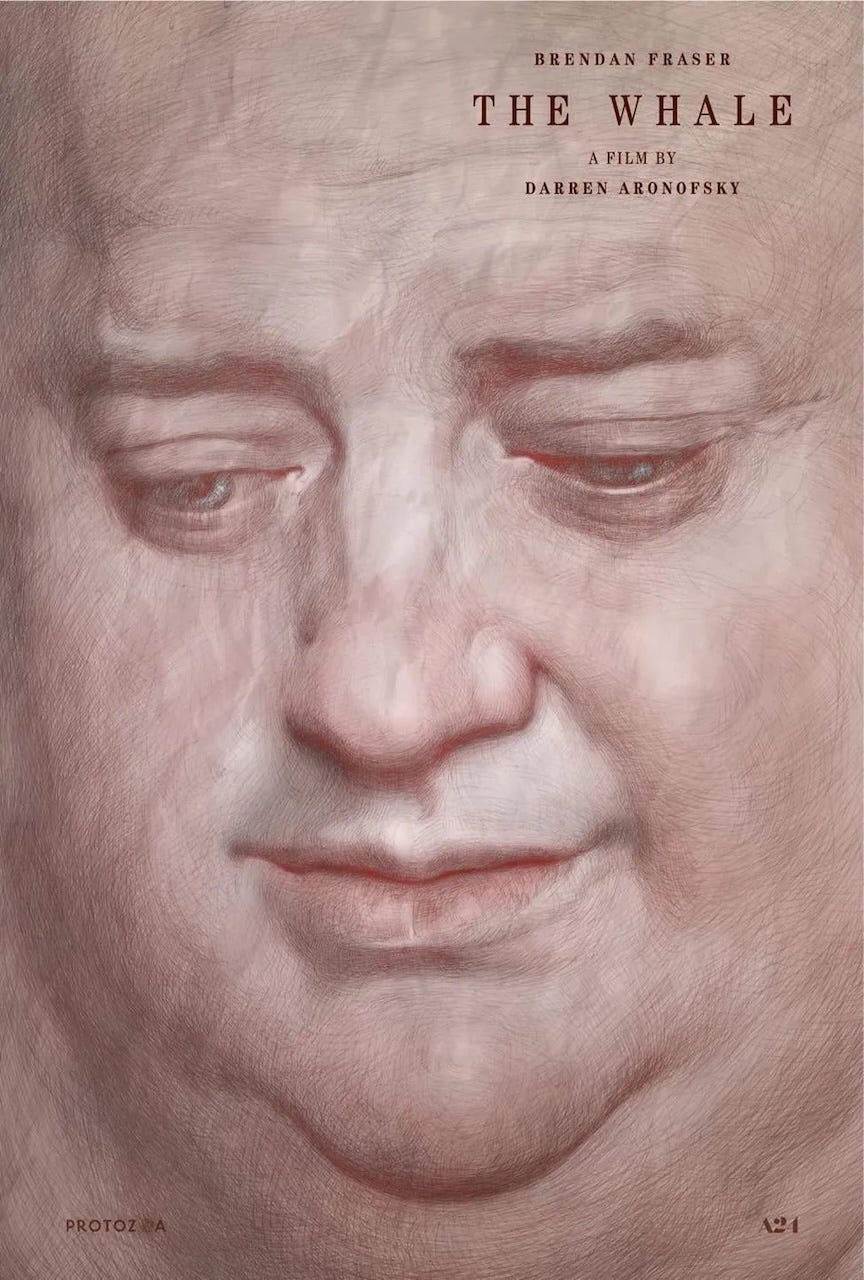

Alongside this part of the conversation, I’ve inserted a series of images of the movie posters that James has done. I really appreciate how James has embraced the crossover side of his practice as a draftsman and painter, and not only for the audiences that these posters are able to reach beyond the gallery and the museum. It’s no coincidence that he’s done the artwork for some of the very best films of the past decade. I think his posters elevate the movies themselves in a really interesting way, inserting the visual storytelling of auteur filmmaking—one of the most important image cultures we have today—into the eternal spirals of timeless myth and imagination.

If you enjoy conversations like these, please subscribe to Nostos! And if you can afford it, I would be very grateful if you would consider upgrading to a paid subscription. These subscriptions allow me to give the Lives of the Artists interviews and the other writing I’m doing here the time and attention they deserve.

Tell me more about the home and studio space.

James Jean: The place we moved into used to be an art gallery. It was part of a three-house compound. There was a tiny house in the middle with a pool, and another regular house, and then the third house which was a gallery for the previous owners. The gallery building was designed by Frank Gehry in 1976. It was his first residential commission. A developer bought the property and split it up into three separate lots. They’d already done a few renovations, and the gallery house was in pretty bad shape, and then they decided to sell. I saw the listing when it had been on the market for a long time, almost a year. It was a hard sell probably because there were no windows. It’s a big white box with no light. It definitely needed a full renovation. When I saw it, I felt it was perfect for us, especially being in a historic Japanese neighborhood. Two blocks away from our house there are numerous Asian restaurants and a Japanese supermarket, all super walkable and tailored for the Japanese community. So I just thought it was perfect. And I had friends in the neighborhood too.

It took a year and a half to renovate. The bedrooms are upstairs, and then the main floor was my studio. It’s got 12-foot ceilings and it’s basically a large white box with a large pivoting wall, so it can transform if needed. The configuration of the house and the office shifted over time as the family evolved. We stayed in a bedroom downstairs for a while, because it was easier to watch the baby on one floor. Then as he got older we transitioned upstairs, and the initial bedroom turned into my office, and then my painting area. Now I’ve moved the studio out of the house. I moved down the street into another house, which is a block away. The new place is just fully for my own work. It’s not as large or as interesting as the house we live in, but it’s very quiet, and I’m more in control of the environment. This house is much more organized. The house with the family is chaotic with the dog and the cooking and the homework and the toys and everything that goes on, and it got to be a little too much. I needed my own space, and luckily this place was available just a few houses down the street.

What are the rules? Is your son allowed into the studio?

There’s no rules. He comes by sometimes to play ping pong, and sometimes when he has playdates, I’ll bring them here to hang out. But he’s mostly at the other house. He’s got a lot of room to roam and play. In the Gehry house he’s able to ride around on a scooter because the floor is poured concrete. That floor is probably the best part of the house. Did you see the video I posted today? I’m having him finally contribute to the family business by helping to sell prints. The video is about him being the “Bibliophile,” a character in the print that I’m currently selling. It’s based on him since he’s constantly reading. Not the best material, unfortunately. But even when he’s walking out the door, walking up and down the stairs, his face is constantly buried in a book. I have to tell him to stop when he’s supposed to get ready for bed. Still, it’s better than an iPad, which is destroying our kids’ minds, especially with Roblox and all the micro-transactions and gambling mechanics that they implement in every game. Every single kid is playing Roblox, and that’s going to be the cause of a lot of problems in the future. Already people are betting on anything and everything with Polymarket, the online prediction markets, and all the sports betting that’s legalized now. Roblox is grooming these kids to become gambling addicts. So, we’re trying to navigate these new hazards. And now there’s AI. Even if it’s not in the home, it’s at school. They’re using Google Slides or Canva with AI built in. It permeates everything.

As an artist and as a parent, what do you think is important in the way that we educate kids now?

I think having them try as many things as possible is the best way to help them find that spark of interest, inspiration or motivation. We’ve tried piano lessons, jiu-jitsu, soccer, all these different sports. With karate he has finally developed the motivation to keep that going. Other sports didn’t go well. Having good instructors is key. We went to this famous jiu-jitsu gym near us, and the instructors were not good with kids, really mean and not compassionate. He would get anxious before each lesson and throw up in the locker room. With karate he’s been able to feel encouraged by leveling up, earning the belts, doing well in competitions. Also, his mom is very dedicated to bringing him to the lessons. It’s Kyokushin karate, so he’s able to do that in Japan over the summer too.

To bring it back to my parents, they didn’t show me anything. Everything I learned about culture and the world, I learned on my own. My parents were so focused on working and surviving and supporting the family. Our conversations were always very surface level. That’s something I was always a bit sad about. I would have breakfast with my parents, but there’d be no conversation at all. I’d read the newspaper, and my dad would read the Chinese paper, and it was very silent. Now, my son asks a lot of questions, and I try to answer them to the best of my ability. When he was younger, he would ask me questions like, Why was I born? Or, why am I afraid to die? Difficult existential questions. Now the questions have evolved into, What is a floppy disk? How does it work? What was Netflix like? How was it different from Blockbuster? How is a DVD different from a CD? How do you use a VCR? Is the Neo Geo better than Turbografx-16? I’m looking forward to introducing him to movies, movies that were influential in my childhood. I was just telling him about Akira Kurosawa and Seven Samurai and how that inspired Star Wars, and High and Low and how that inspired a lot of the crime dramas we see now.

He’s really into manga and anime right now. He’s really impressed with Mob Psycho 100, which is the same creator as One-Punch Man, which is about that existential idea of, what do you do if you’re the most powerful being in the universe and you can defeat any adversary with a punch? My son was also impressed that the creator couldn’t really draw and uploaded his stories on the web on his own. The web comic gained traction because he just wouldn’t stop uploading, and eventually he got to work with a really famous, amazing artist to bring his stories to life.

The only thing we’re very strict about is language. Again, that relates to my childhood, where I lost the ability to speak Chinese. I want to make sure he’s at least able to read and write Japanese. So, he only speaks to his mother in Japanese and goes to tutoring twice a week and Japanese school on Saturdays, plus two months of public school in Tokyo. Thankfully, his language skills are pretty decent. With everything else, I’m at the mercy of the culture that the kids are immersed in now. We’ve gone through mewing and skibidi toilet and rizz, and I fear what comes next.

The work of sorting through all of the crap that’s out there and finding something interesting and then taking it to the next level—that’s what we do, that’s what everyone’s supposed to do. But I don’t know how people are going to hone their taste or their eye in this generation.

It’s difficult because there’s no consensus reality. We were all viewing the same media as children, and you could navigate to the alternative or fringe parts of the spectrum if you wanted. Now the algorithms tailor everything to your own particular interests, and a lot of it is very pernicious brain rot. With editors and gatekeepers the brain rot was kept at bay. You had to actively seek out the interesting and weird stuff, like public access television. Now it’s everywhere and all the kids are addicted to it. Culture and technology and society are evolving at such a fast rate that it’s becoming impossible to establish a contemporary canon of quality. In the school parent group chat there are warnings about AI chat bots talking your kids into committing suicide. On Netflix, the number one documentary right now is Unknown Number. It’s a true story about this high school girl who was getting thousands of harassing and sexual texts, telling her to kill herself. No one could figure out where it was coming from, the police were involved and eventually the FBI, and then the FBI found out that all these texts were coming from her own mother.

The root of the problem is the phones. We’re going to avoid that as long as we can. A lot of the kids chat via FaceTime or messenger on their iPads even if they don’t have phones. There is a class group chat, but my son is not in it. There are a couple other kids whose parents don’t let them on the group chat. But in the parent chat there have been some complaints about the boys saying inappropriate stuff about the girls. I’m so relieved that my son is not involved. I feel like my son isn’t quite ready yet to deal with this type of social dynamic, to have his inappropriate jokes consecrated in a text chain.

Recently, my son became friends with another kid whose dad has shown his 10 year old son all the Terminator movies, all the Alien movies, all these classic R-rated films. The kid likes Kendrick Lamar. When you see them together, they’re just kids, but then all of a sudden you’ll hear the kid say a line from a Kendrick song, and I don’t know if my son’s ready for that. I do want to introduce him to more mature material soon, and that’s something I’m trying to figure out now. Early or late, it’s always going to be traumatic in some way. It cracks something open.

Does your son appreciate your work?

He doesn’t have much interest in it. He doesn’t draw or paint at all. He does have a sense of what I do. As far as art goes, he’s mainly fixated on manga and anime. I’m trying to get him to appreciate the artwork more, because he’s more interested in the story. He flips through the pages and reads way too fast. I think he’s starting to understand the different storytelling techniques that the artists will use, noticing those details and appreciating them. It’s hard to know what’s happening in his head, it’s all developing so quickly.

I want to go back to your work. I think your work treats childhood and intergenerational family relationships in a really interesting way. Is this idea of family or kinship important to how you think of your practice?

I think it’s more of an incidental effect of the work I like to make, which is generally narrative in nature. There was a marked change when my son was born and we moved back to LA. My world changed and the studio was filled with children’s books and colorful plastic toys and I was stepping over things all the time. In 2018, when he was three, I did a show at Kaikai Kiki with a lot of bright colors and imagery that was inspired by an Italian children’s book illustrator, Antonio Rubino, who did these really vibrant images of flower people in dazzling combinations of shapes and colors. That early period of being a father was a big shift for me, retreating back to innocence. In my 20s and early 30s, things got really dark. A lot of messed-up stuff happened in my life, and the work was really dark and violent. But when I got into a new relationship and my son was born, everything reset. I was being pulled in different directions, which made me focus during the time I had to devote to painting.

That initial body of work created a whole new way of working with my assistants, too, because I was able to formalize a way of making these paintings. That’s partially down to the influence of Takashi Murakami. I started to create digital color studies and color swatches that we would match by hand, and it led to a set process for making the paintings. It’s a process that I’m now trying to break out of. It’s been almost ten years now, so it’s time for a change. Now I’m trying to figure out a way to return to what I was doing in my early 20s, when I was more innocent and not as much in my head about a lot of things. Returning to that initial purity of creativity is more naive, in a way. I was doing a lot of work in my sketchbooks that had a very sincere energy, and that still resonates with a lot of people. I want to get back to that feeling of not knowing what I’m doing.

It’s been 25 years now, and I’ve made so much stuff that sometimes the process becomes too predictable. Say I’m making a sketch for a movie poster. Even though I don’t know exactly how it will go, I’m always trying to find those moments of unexpected spontaneity, a moment of inspiration where you’re struck by something that’s beyond comprehension. You don’t know where it came from, but it’s this moment in the piece that makes you feel like you’re not in control, like you’re a vessel for the divine.

I want to carve out space for those magical moments of divine intervention. But I don’t know if that’s possible as I get older. A lot of the great artists, or mathematicians, have their great insights when they’re in their early 20s, and if they haven’t by the time they’re 30, then basically they’re done.

Mature style and late style for artists are really important. There are some who crystallize and end up at a point of clarity,, but then there are also those who find a new sense of freedom. Once they’ve defined their thing, then they can break out of that. It’s always beautiful to be able to follow that in an artist’s career. As someone looking at art, you want to be surprised. You don’t want to know in advance what’s coming next. The danger is when the practice becomes too planned out. Like what you were saying about trying to plan out the future for your kids—the more you try to control the outcome, the more you invite unexpected challenges.

Sure, in that sense, I don’t want to do everything now. I want to have space left in my timeline to look forward to, that point where everything crystallizes and becomes something new. Maybe in my 50s or 60s, I’ll feel more free, but that’s not to say I’m not enjoying what I’m doing now. But currently the structure is more contained in that masochistic way. I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to fully unchain myself again.

My parents had a very prescribed way in which they thought I would grow up: piano lessons, straight A’s, frugal, very typical Asian-American experience. I still have trauma from not being able to wear nice clothes. I would draw “AIR” underneath the Nike swoosh with a sharpie because it was cooler to have the sole with the plastic bubble inside. Now, shoe companies send me stuff. It’s a totally different experience now for my son, though I don’t know if we’ve set him on the optimal path. He goes to a progressive independent school here in LA. When he goes to school in Japan, the teachers say he’s a normal student. At school in LA there’s a lot of issues, emails and meetings with counselors, and so on. It’s interesting, having him grow up between those two different cultures and seeing how he adjusts to them. He gets to have me as this very Americanized father, and his mother who is very Japanese—she even wakes up at 5am to make him fancy bento boxes.

Bento boxes and school therapy. It’s the best of both worlds.

Thanks for following. I hope you’ve enjoyed this conversation as much as I have. I’ll be back next week with some books I’ve read and exhibitions I’ve seen recently, as well as a few takeaways from this interview and some notes for upcoming conversations. Hope your road home is a long one.

Read the first half of this conversation with James here: